From David Ruccio While Amazon let it slip last week that its Prime program—the annual membership that offers discount pricing and free 2-day shipping—now tops 100 million members, there’s another number people might be curious about: the company’s average annual wage, which Amazon revealed in compliance with a new regulation that asks companies to show a comparison between an average worker’s wage and the salary of their CEO. Amazon has reported an average compensation for its varied, mostly warehouse (and now, with Whole Foods, grocery store), workers at ,446 a year. The federal government defines its poverty guideline for a family of four to be ,100. So, Amazon’s average wage falls easily within 150 percent of the poverty line—and stands at about one-half of the median

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

While Amazon let it slip last week that its Prime program—the annual membership that offers discount pricing and free 2-day shipping—now tops 100 million members, there’s another number people might be curious about: the company’s average annual wage, which Amazon revealed in compliance with a new regulation that asks companies to show a comparison between an average worker’s wage and the salary of their CEO.

Amazon has reported an average compensation for its varied, mostly warehouse (and now, with Whole Foods, grocery store), workers at $28,446 a year. The federal government defines its poverty guideline for a family of four to be $25,100. So, Amazon’s average wage falls easily within 150 percent of the poverty line—and stands at about one-half of the median household income in the United States.

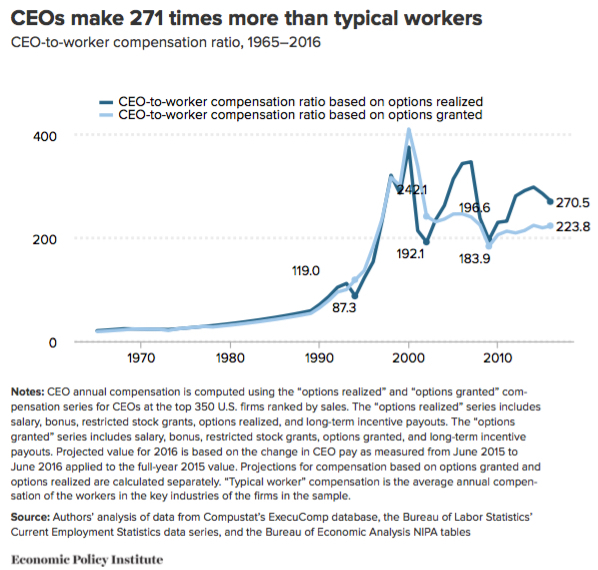

No wonder, then, that Amazon is owned and run by literally the richest man in the world, Jeff Bezos. While he technically “made” only $1.7 million last year, he’s worth $127 billion.* So it means on paper, Bezos makes $59 for every dollar an average employee earns, which is actually a smaller ratio than the average of 271 to 1 for the largest 350 U.S. corporations (pdf).

While Amazon may not have been thrilled by being forced to reveal this not-so-flattering wage comparison, they do have one thing going for them: the only private employer bigger than the e-commerce giant is their retail competitor Walmart, whose workers average only $19,177 per year, putting them far under the federal poverty guidelines. Moreover, the ratio to average-worker pay of Walmart CEO Doug McMillon, who took in $22.8 million last year, was an astounding 1,188 to 1.

And the extraordinary numbers continue, across the economy. Royal Caribbean Cruises: 728-1. Regeneron Pharmaceuticals: 215-1. Netflix: 133-1. Live Nation Entertainment: 2,893-1. Honeywell International: 333-1. Fidelity National Information Services: 654-1. UnitedHealth Group: 298-1. And on and on.

Each such ratio indicates the obscene level of inequality in the United States, based on the amount of surplus pumped out of workers and distributed to those who run American corporations on behalf of their boards of directors.

While the figures of CEO-to-average-worker-pay are being reported in the business press, they have not been widely discussed in the media or by the nation’s politicians. It should come as no surprise, then, that Americans underestimate—by a wide margin—the degree of inequality in the United States.

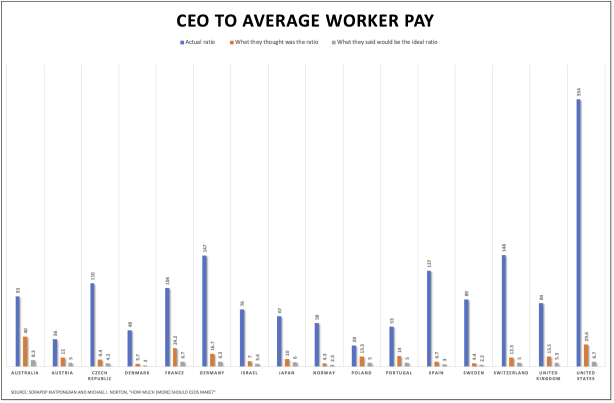

In a 2014 study, Sorapop Kiatpongsan and Michael Norton asked about 55,000 people around the globe, including 1,581 participants in the United States, how much money they thought corporate CEOs made compared with unskilled factory workers.** Then they asked how much more pay they thought CEOs should make. American respondents guessed that executives out-earned factory workers roughly 30-to-1—just about what that ratio was in the 1960s and exponentially lower than the actual estimate at the time of 354-to-1. They believed the ideal ratio should be about 7-to-1.

As it turns out, Americans didn’t answer the survey much differently from participants in other countries. Australians believed that roughly 8-to-1 would be a good ratio; the French settled on about 7-to-1; and the Germans settled on around 6-to-1. In every country, the CEO pay-gap ratio was far greater than people assumed. And though they didn’t concur on precisely what would be fair, both conservatives and liberals around the world also concurred that the pay gap should be smaller. People also agreed across income and education levels, as well as across age groups.

Why should this matter?

Because representations of the economy that minimize the existence of inequality or the problems associated with inequality are bound to reinforce the systematic misperceptions found by Norton and others.

That’s exactly what much mainstream economics accomplishes. It deflects attention from the existence of inequality (e.g., by focusing on growth, output, and the price level versus distribution) and from the economic and social problems created by inequality (by attributing the growing gap between the haves and have-nots to forces like globalization and technological change that are beyond our control or invoking more education as the only solution).

Mainstream economics therefore forms part of what others (such as Vladimir Gimpelson and Daniel Treisman) refer to as “ideology,” “which may predispose people to ‘see’ the level of inequality that their beliefs and values convince them must exist.” And the strength of mainstream economics in the United States—in colleges and universities as well as in the media, think tanks, and in government—and around the world is one of the main reasons Americans, like people in other countries, tend not to see the existing degree of inequality.

On the other hand, the ideology of mainstream economics is never complete. That’s why Americans and citizens around the globe do see that the degree of inequality created by existing economic arrangements is fundamentally unfair.

It’s that sense of unfairness, which is only partially masked by mainstream economics, that can serve as the basis for a radical rethinking and reimagining of contemporary economic and social institutions.

*Bezos [ht: sm] received a hostile reception from workers when he arrived in Berlin to pick up an innovation award last Tuesday. As Frank Bsirske, the head of the Verdi trade union, explained: “We have a boss who wants to impose American working conditions on the world and take us back to the 19th century.” Meanwhile, back in the United States, Amazonreported that its profits more than doubled to $1.6 billion in the first quarter of 2018, sending shares of its stock soaring to an all-time high.

**This is the second high-profile paper in which Norton discovered that Americans have a notion of economic fairness that is strikingly more equal than the current reality, and more equal even than their own underestimate of the degree of inequality.