From David Ruccio First there was the Great Gatsby curve. Then there was the Proust index. Now, thanks to Neil Irwin, we have the Marx ratio. Each, in their different way, attempts to capture the ravages of contemporary capitalism. But the Marx ratio is a bit different. It was published in the New York Times. Its aim is to capture one of the underlying determinants of the obscene levels of inequality in the United States today—not class mobility or the number of years of national income growth lost to the global financial crash. And, of course, it takes its name from that ruthless nineteenth-century critic of mainstream economics and capitalism itself. Now, to be clear, there are lots of ratios than can be found in Marx’s critique of political economy—for example, the rate of

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

First there was the Great Gatsby curve. Then there was the Proust index. Now, thanks to Neil Irwin, we have the Marx ratio.

Each, in their different way, attempts to capture the ravages of contemporary capitalism. But the Marx ratio is a bit different. It was published in the New York Times. Its aim is to capture one of the underlying determinants of the obscene levels of inequality in the United States today—not class mobility or the number of years of national income growth lost to the global financial crash. And, of course, it takes its name from that ruthless nineteenth-century critic of mainstream economics and capitalism itself.

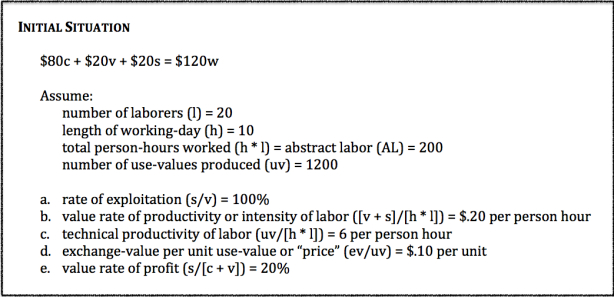

Now, to be clear, there are lots of ratios than can be found in Marx’s critique of political economy—for example, the rate of exploitation, the intensity of labor, the technical productivity of labor, the exchange-value per unit use-value, and the value rate of profit (as illustrated above in a fragment from one of my class handouts)—and the ratio Irwin presents is not one of them.

But that doesn’t make Irwin’s ratio wrong, or uninteresting. On the contrary.

Basically, what Irwin has done is take the data from corporate financial reports (net income and number of employees) and from a minor provision of the Dodd-Frank Act, which requires that publicly trade corporations reveal the gap between what they pay their CEOs and their average worker (and thus report median worker pay) and calculated a number:

The Marx Ratio, as we’re calling it, captures the relationship between a company’s profits — the return to capital, on a per-employee basis — and how much its median employee is compensated, a rough proxy for the return to labor.

Thus, for example, Wells Fargo, which reported $22.2 billion in net income in 2017, with 262,700 employees and median worker pay of $60,446, had a Marx ratio of 1.40. Similarly, we have the same number for other corporations—from the relatively small real estate investment trust Duke Realty (37.7) to independent energy company Hess (-12.2).

Irwin is clear: notwithstanding the limitations in the data, “companies with high Marx Ratios offer particularly strong rewards to their shareholders relative to workers.”* But that doesn’t mean, contra Irwin, that “Numbers below 1 signal the reverse: a more favorable return to labor.” Any positive number indicates that, after paying all expenses (including workers’ wages, taxes, interest on debt, deductions for depreciation, and CEO salaries), the net income or profit per employee is positive.

In fact, with a little algebraic manipulation, Irwin’s Marx ratio turns out to look a lot like Marx’s rate of exploitation.**

They’re not the same, of course. First, because corporate net income leaves out many of the distributions of surplus-value corporate boards of directors make—such as interest payments, taxes, and managers’ salaries—and the number of employees refers to all workers, not just nonmanagerial workers. Second, because the Irwin ratio is calculated for all publicly traded companies and therefore makes no distinction between finance, real-estate, insurance and companies that actually produce goods and services. From a Marxian perspective, the former capture surplus-value that is produced and appropriated elsewhere in the economy (both nationally and globally).

So, the Marx ratio is not Marx’s ratio.

But Irwin’s Marx ratio does tell us a great deal about how wildly profitable American corporations are, especially in comparison to how little they pay their employees—to the tune of 3, 4, 30 times what the average worker makes. And that’s one of the principal causes of the obscene and growing levels of inequality we’ve seen in the United States for decades now.

I, for one, would love to see the Marx ratio reported in the financial news on a regular basis. Alongside the ratio of CEO to average worker pay. And, even better, Marx’s own indicator of capitalist class injustice, the rate of exploitation.

*The data are a bit of a problem, especially because median worker pay is based on self-reporting:

The denominator is the compensation to the median employee, as disclosed in the company’s proxy statement, which can create distortions in representing rank-and-file employees.

Companies also have some degree of flexibility in how they calculate median pay, so comparisons are not necessarily apples-to-apples. For example, they may choose to use statistical sampling instead of actual payroll records, and may exclude non-U.S. employees depending on privacy rules in overseas markets.

A better number for the idea we’re really trying to get at would be average compensation for nonexecutive employees, but companies aren’t required to report that publicly.

**Mathematically, Irwin’s Marx ratio is (NI/L)/(W/L), which turns out to be NI/W, where NI is net income, L is the number of employees, and W is the wage bill (calculated by multiplying median worker pay by the number of employees). Meanwhile, Marx’s rate of exploitation is S/V, where S is the amount of surplus-value and V is the value of labor power.