From David Ruccio Millennials may be the largest, best educated, and most diverse generation in U.S. history. But they’re also generation screwed. As a result, they’re more likely than their elders to think of themselves as working-class and less likely to identify as middle-class. The large downshift in class identity among young adults is explained by the fact that they are being left behind—with lower earnings, fewer jobs, more part-time employment, and a higher unemployment rate than any other generation in the postwar period. And while it is true that recent college graduates make more than young workers with a high-school diploma, the annual real wages of both groups have declined since 2009. So, it should come as no shock that most Millennials have nothing saved for

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

Millennials may be the largest, best educated, and most diverse generation in U.S. history. But they’re also generation screwed. As a result, they’re more likely than their elders to think of themselves as working-class and less likely to identify as middle-class.

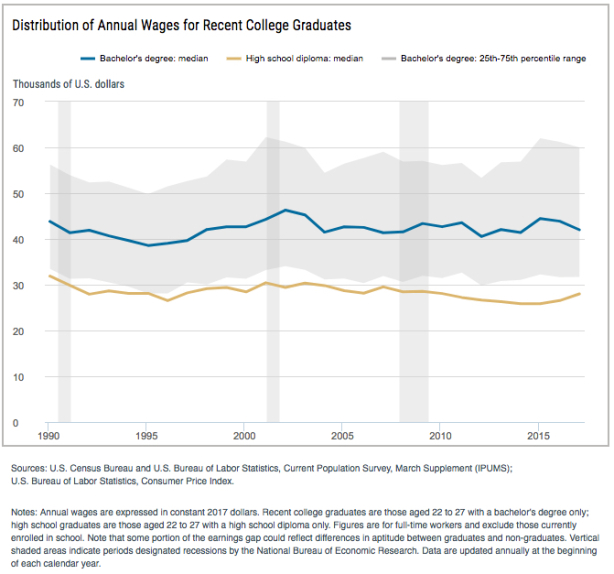

The large downshift in class identity among young adults is explained by the fact that they are being left behind—with lower earnings, fewer jobs, more part-time employment, and a higher unemployment rate than any other generation in the postwar period.

And while it is true that recent college graduates make more than young workers with a high-school diploma, the annual real wages of both groups have declined since 2009.

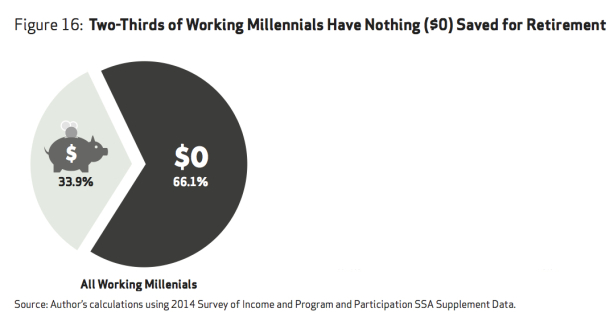

So, it should come as no shock that most Millennials have nothing saved for retirement, and those who are saving can’t save nearly enough.

According to the National Institute on Retirement Security, in research that was recently reported by CNN, two-thirds of working Millennials have not been able to save anything for their retirement. That’s true even though two-thirds of Millennials work for an employer that offers an employer-sponsored retirement plan. But they’re often not eligible, because they work part-time or have too little time in their current job—and, if they are eligible, their low pay and high indebtedness make it impossible to set aside anything for retirement savings.

The fact that Millennials aren’t following the recommendations of financial and retirement experts has a lot of people worried. But Keith Spencer [ht: ja] presents a much more hopeful perspective: many millennials honestly don’t see a future for capitalism.

The idea that we millennials’ only hope for retirement is the end of capitalism or the end of the world is actually quite common sentiment among the millennial left. . .

Older generations, and even millennials who are better off and who have managed to achieve a sort of petit-bourgeois freedom, might find this sentiment unimaginable, even abhorrent. And yet, in studying the reaction to the CNN piece and reaching out to millennials who had responded to it, I was astounded not only at how many young people shared [Holly] Wood’s feelings, but how frequently our expectations for the future aligned. Many millennials expressed to me their interest in creating self-sustaining communities as their only hope for survival in old age; a lack of faith that capitalism as we know it would exist by retirement age; and that alternating climate crises, concentrations of wealth, and privatization of social welfare programs would doom their chance at survival.

Creating a world in which individual retirement savings are made irrelevant is a kind of real talk from Millennials that makes a helluva lot more sense than the constant barrage of so-called expert advice to educate “Millennials about the value of retirement savings and how employer-sponsored retirement plans and employer matches work.”

In fact, socialism may be the best way “to improve the retirement preparedness of America’s largest generation.”