From David Ruccio The warnings about the consequences of global warming are becoming increasingly dire. And with good reason. Just last month, a report by a multidisciplinary research team published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences made the case that even fairly modest future carbon dioxide emissions could set off a cascade of catastrophic effects, with melting permafrost releasing methane to ratchet up global temperatures enough to drive much of the Amazon to die off, and so on in a chain reaction around the world that pushes Earth into a terrifying new hothouse state from which there is no return. Civilization as we know it would surely not survive. Climate change during the Capitalocene (in its last stage?) has also spawned a new genre of science fiction

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

The warnings about the consequences of global warming are becoming increasingly dire. And with good reason.

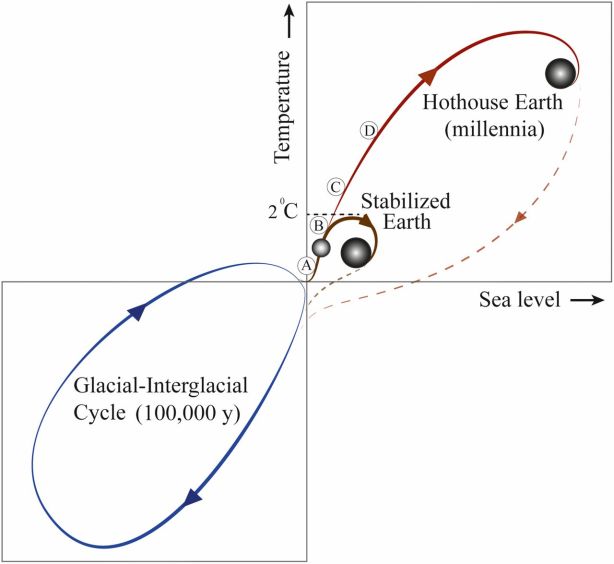

Just last month, a report by a multidisciplinary research team published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences made the case that even fairly modest future carbon dioxide emissions could set off a cascade of catastrophic effects, with melting permafrost releasing methane to ratchet up global temperatures enough to drive much of the Amazon to die off, and so on in a chain reaction around the world that pushes Earth into a terrifying new hothouse state from which there is no return. Civilization as we know it would surely not survive.

Climate change during the Capitalocene (in its last stage?) has also spawned a new genre of science fiction novels—the so called cli-fi (climate change fiction) genre. It includes Octavia E. Butler’s The Parable of the Sower, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, Kim Stanley Robinson’s the Science in The Capital trilogy, Margaret Atwood’s The Maddaddam trilogy, Nathaniel Rich’s Odds Against Tomorrow, Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior, and Jeff VanderMeer’s TheSouthern Reach trilogy.

Both the scientific and fictional literatures now paint a distinctly dystopian picture for planet Earth—unless, of course, radical changes are made to mitigate the effects and eliminate the sources of global warming.

It’s not clear to me which way the dystopian tenor of recent attempts to grapple with the consequences of climate change cuts. I know all kinds of people—students, friends, and neighbors—for whom the impending apocalypse generates intense and sustained activity to both publicize and push for changes to curtail global warming. However, Per Espen Stoknes, a psychologist and economist recently appointed to the Norwegian Parliament, warns that dystopian scenarios may overdo the threat of catastrophe, making people feel fear or guilt or a combination of the two.

But these two emotions are passive. They make people disconnect and avoid the topic rather than engage with it.

One group that does engage with climate change generates an equal amount of passivity: the technological utopians. They promise a kind of magical, technical fix to the problem of global warming.

We’ve all seen their proposals: Growing kelp. Cap-and-trade markets. Behavioral “nudges.” Also, nuclear fusion, supercapacitor batteries, lab-grown meat, carbon engineering, and smart cities. In fact, Bill Gates, along with some of the world’s richest people (such as Jeff Bezos from Amazon, Jack Ma from the Ali Baba group, and Richard Branson), has launched the Breakthrough Energy Coalition to invest in solutions driven by technology. It promises to bring together governments, research institutions, and billionaire investors to limit climate change.

As I explained back in June, few if any of the contemporary affluent, high-tech enthusiasts have even considered the possibility that, far from being innovative or unusual, their campaigns are part and parcel of a longstanding tradition of technological utopianisms.

They are merely the latest in a long line—starting with the late-sixteenth- and early-seventeenth-century Pansophists (such as Tomasso Campanella, Johann Valentin Andreae, and Francis Bacon) through the utopian socialists of the early nineteenth century (especially Henri de Saint-Simon) through the numerous technological utopians of the late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth centuries (including Edward Bellamy, Henry Olerich, Edgar Chambliss)—of prophets of progress and the possibility of achieving utopia through the introduction and expansion of new technologies.

Fortunately, people are beginning to sound the alarm about purely technological solutions to climate change. Adam McGibbon [ht: db], for example, warns that “geoengineering projects are fraught with unintended consequences”:

Scientists don’t know how spraying clouds with sea water would affect precipitation, potentially devastating the food systems. Dumping iron filings in the ocean would have unknown effects for marine life. Injecting aerosols into the atmosphere could cause droughts. Meddling with climatic systems we don’t understand, in the service of solving global warming, could just make the crisis worse.

But unintended consequences are associated with any attempt to radically change existing arrangements—or, for that matter, of not changing them.

As I see it, the biggest problem with technological utopianism is not unintended consequences (although they may be substantial), but that it takes politics out of the equation—whether in imagining solutions to economic and social problems or refashioning the role of technology in a radically different kind of economy and society. Technology thus becomes a substitute for politics. As Aleszu Bajak has recently explained with respect to finding a solution to climate change,

Relying on a technological fix that’s just over the horizon avoids the mountain moving required to wean ourselves off fossil fuels, bring hundreds of countries into agreement on how to limit and clean up emissions, and alter the consumption habits of an entire civilization. Those are systemic complexities ingrained in our economies and cultures. Propping up glaciers to limit sea level rise, sprinkling iron dust into the oceans to encourage plankton growth to absorb carbon, or spraying the skies to reflect the sun’s heat just seems simpler.

That doesn’t mean utopia is irrelevant to the problem of climate change. On the contrary. The dystopian consequences of current trends clearly invite a utopian response. But it needs to be of a different nature from the various forms of technological utopianism that are currently circulating.

It starts with a critique of the discourses, activities, and institutions that together, within the Capitalocene, have led to concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere that have reached (and, by some accounts, will soon surpass) the ceiling with regards to acceptable climate risk. What I’m referring to are theories that have normalized and naturalized the current set of economic and social structures based on private property, individual decision-making in markets, and class appropriation and distribution of the surplus; activities that have accelerated changes in the Earth system, such as greenhouse gas levels, ocean acidification, deforestation, and biodiversity deterioration; and institutions, such as private corporations and commercial control over land and water sources, that have had the effect of increasing surface ocean acidity, expanding fertilizer production and application, and converted forests, wetlands, and other vegetation types into agricultural land.

Such a ruthless criticism brings together ideas and activists focused on the consequences of a specific way of organizing economic and social life with respect to the global climate as well as the situations of the vast majority of people who are forced to have the freedom to try to eke out a living and maintain themselves and their communities under present circumstances.

Broadening participation in that critique, instead of directing hope toward a technological miracle, serves to create both a shared understanding of the problem and the political basis for real solution: a radically transformed economic and social landscape.