From David Ruccio We’re ten years on from the events the triggered the worst crisis of capitalism since the first Great Depression (although read my caveat here) and centrists—on both sides of the Atlantic—continue to peddle an ahistorical nostalgia. Fortunately, people aren’t buying it. As Jack Shenker has explained in the case of Britain, one of the most darkly humorous features of contemporary British politics (a competitive field) is the ubiquity of parliamentarians, pundits and business titans who wail and gnash at our ceaseless political tumult but appear utterly incurious about the conditions that produced it. . . Such stalwart defenders of a certain brand of “common sense” capitalism have watched in horror as ill-mannered upstarts — on both the right and the left — build power

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

We’re ten years on from the events the triggered the worst crisis of capitalism since the first Great Depression (although read my caveat here) and centrists—on both sides of the Atlantic—continue to peddle an ahistorical nostalgia.

Fortunately, people aren’t buying it.

As Jack Shenker has explained in the case of Britain,

one of the most darkly humorous features of contemporary British politics (a competitive field) is the ubiquity of parliamentarians, pundits and business titans who wail and gnash at our ceaseless political tumult but appear utterly incurious about the conditions that produced it. . .

Such stalwart defenders of a certain brand of “common sense” capitalism have watched in horror as ill-mannered upstarts — on both the right and the left — build power at the fringes. But these freshly emboldened centrists pretend that the rupture has no connection to their own dogma and seem to envision the whole sorry mess as some sort of administrative error that will be swiftly tidied away once the right person, with the right branding, is restored to authority.

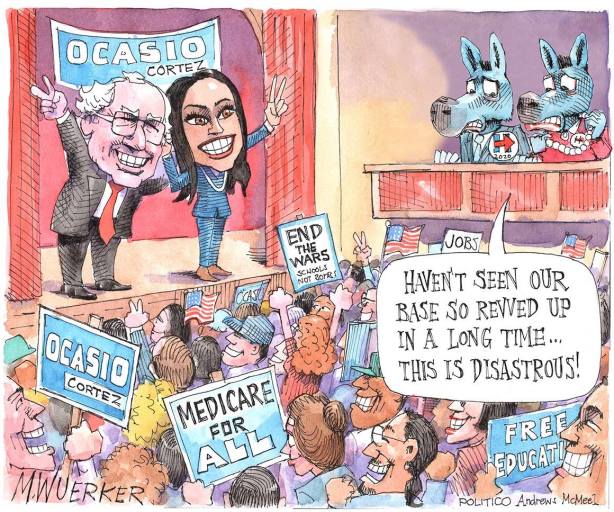

Much the same is true in the United States, where centrists in the Democratic Party watch in horror as the Republican Party falls in lockstep with Donald Trump and the only energy within their own party comes from the Left. All the while, they ignore their own role in creating the conditions for the crash and the fact that their technocratic promises to American young people—university or community-college education leading to a stable and prosperous worklife, the dream of a thriving middle-class democracy, the claim for capitalism’s economic and ethical superiority—lie in tatters.

As it turns out, Jürgen Habermas sounded the warning of just this eventuality back in the mid-1980s.* His argument, in a nutshell, is that western cultures had used up their utopian energies—and for good reason, because

the very forces for increasing power, from which modernity once derived its self-confidence and its utopian expectation, in actuality turn autonomy into dependence, emancipation into oppression, and reality into the irrational.

In particular, the social welfare state—based on Keynesian economic policies and democratic politics (with a social basis in independent labor unions and labor-oriented parties)—had lost “its capacity to project future possibilities for a collectively better and less endangered way of life.”

The reactions to this crisis are well known: on the Right, the rise of neoliberalism associated with Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan; on the Left, the celebration of non-party social movements. And, in the center? “Those who defend the legitimacy of industrial society and the social welfare state”—such as the more conservative wing of the Social Democrats (he mentions the Mondale wing of the Democrats in the United States and the second government of François Mitterand in France)—who “have been put on the defensive.”

I would make it even sharper: the center refashioned itself in the mould of the right-wing neoliberals, at least in part to isolate and contain the criticisms from the Left, by emphasizing individual (not collective) initiative and market-based (not social or solidarity) solutions to economic and social problems. As a result, the center lost its utopian impulse and settled for a meek defense of what remained of the social welfare state.

Habermas’s view is that society has been reoriented away from the concept of labor toward that of communication, which requires a different way of “linking up with the utopian tradition.” The alternative approach would be to rethink the concept of labor in terms of class and analyze the ways in which the forces of capital that were supposed to be regulated and contained by the social welfare state were left with both the interest and means to undo those regulations. And it’s the center that put itself in the position of responding to and representing the progressive dismantling of the economic side of the social welfare state—in deregulating finance, pursuing globalization, and helping to unleash new digital technologies. The result was, not surprisingly, the growth of obscene levels of inequality, increasing precariousness for large parts of the working-class, and finally the crisis that broke out in 2008, which has led not only to economic but also political breakdown.

However, as Shenker correctly observes, “the breakdown of any political order can be both emancipatory and revanchist.” And it now falls to the Left to reharness and reinvigorate the utopian impulses and energies that the center has squandered in order to chart a path forward.

*The English-language translation of Habermas’s article, “The New Obscurity: The Crisis of the Welfare State and the Exhaustion of Utopian Energies,” was first published in Philosophy & Social Criticism. The article, with a slightly different title (“The Crisis of the Welfare State and the Exhaustion of Utopian Energies”) and translation, was reprinted in On Society and Politics: A Reader. According to a friend and colleague who is a Habermas expert [ht: db], the essay is typical of his thinking that issued from what most people still consider Habermas’s most important work, The Theory of Communicative Action. “I would characterize Communicative Action as his middle period, which follows his earlier, more Frankfurt-styled emphasis on ideology critique (especially positivism) in books like Knowledge and Human Interests and Theory and Practice. In this middle period, he moved way from negative dialectics à la Adorno and Horkheimer toward developing a positive social theory of his own, one he would say was a “reconstruction” of Marxism but I would call a “replacement,” in which he develops a theory of communicative action to avoid what he sees as productivism and economism in the Marxist tradition.” And he adds: “I find his means of doing so, evolutionary theory, unacceptable.”