From Lars Syll In a post on his blog, Paul Krugman argues that ‘Keynesian’ macroeconomics more than anything else “made economics the model-oriented field it has become.” In Krugman’s eyes, Keynes was a “pretty klutzy modeler,” and it was only thanks to Samuelson’s famous 45-degree diagram and Hicks’ IS-LM that things got into place. Although admitting that economists have a tendency to use ”excessive math” and “equate hard math with quality” he still vehemently defends — and always has — the mathematization of economics: I’ve seen quite a lot of what economics without math and models looks like — and it’s not good. Sure, ‘New Keynesian’ economists like Mankiw and Krugman — and their forerunners, ‘Keynesian’ economists like Paul Samuelson and (young) John Hicks — certainly have

Topics:

Lars Pålsson Syll considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from Lars Syll

In a post on his blog, Paul Krugman argues that ‘Keynesian’ macroeconomics more than anything else “made economics the model-oriented field it has become.” In Krugman’s eyes, Keynes was a “pretty klutzy modeler,” and it was only thanks to Samuelson’s famous 45-degree diagram and Hicks’ IS-LM that things got into place. Although admitting that economists have a tendency to use ”excessive math” and “equate hard math with quality” he still vehemently defends — and always has — the mathematization of economics:

I’ve seen quite a lot of what economics without math and models looks like — and it’s not good.

Sure, ‘New Keynesian’ economists like Mankiw and Krugman — and their forerunners, ‘Keynesian’ economists like Paul Samuelson and (young) John Hicks — certainly have contributed to making economics more mathematical and “model-oriented.”

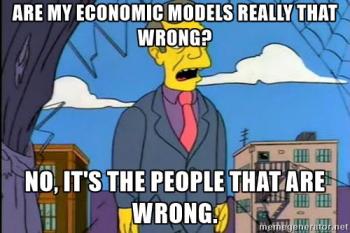

But if these math-is-the-message-modelers aren’t able to show that the mechanisms or causes that they isolate and handle in their mathematically formalized macromodels also are applicable to the real world, these mathematical models are of limited value to our understandings of real-world economies.

But if these math-is-the-message-modelers aren’t able to show that the mechanisms or causes that they isolate and handle in their mathematically formalized macromodels also are applicable to the real world, these mathematical models are of limited value to our understandings of real-world economies.

When it comes to modeling philosophy, Krugman defends his position in the following words (my italics):

I don’t mean that setting up and working out microfounded models is a waste of time. On the contrary, trying to embed your ideas in a microfounded model can be a very useful exercise — not because the microfounded model is right, or even better than an ad hoc model, but because it forces you to think harder about your assumptions, and sometimes leads to clearer thinking. In fact, I’ve had that experience several times.

The argument is hardly convincing. If people put that enormous amount of time and energy that they do into constructing macroeconomic models, then they really have to be substantially contributing to our understanding and ability to explain and grasp real macroeconomic processes.

For years Krugman has in more than one article criticized mainstream economics for using too much (bad) mathematics and axiomatics in their model-building endeavours. But when it comes to defending his own position on various issues he usually himself ultimately falls back on the same kind of models. In his End This Depression Now — just to take one example — Krugman maintains that although he doesn’t buy “the assumptions about rationality and markets that are embodied in many modern theoretical models, my own included,” he still find them useful “as a way of thinking through some issues carefully.” When it comes to methodology and assumptions, Krugman obviously has a lot in common with the kind of model-building he otherwise criticizes.

If macroeconomic models – no matter of what ilk – make assumptions, and we know that real people and markets cannot be expected to obey these assumptions, the warrants for supposing that conclusions or hypotheses can be bridged, are obviously non-justifiable.

A gadget is just a gadget — and brilliantly silly simple models — IS-LM included — do not help us working with the fundamental issues of modern economies any more than brilliantly silly complicated models — calibrated DSGE and RBC models included.