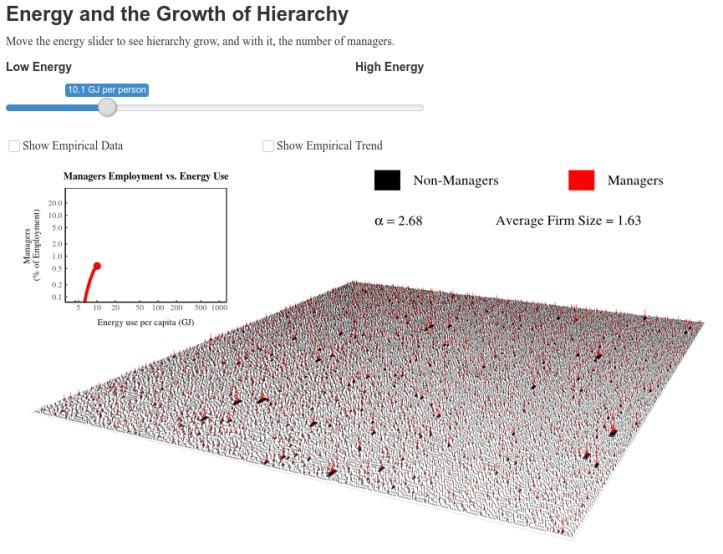

From Blair Fix In The Growth of Hierarchy and the Death of the Free Market, I argued that economic development involves killing the free market. What was the evidence? As energy use increases, so does the relative number of managers. This growth of managers, I argued, indicates that economic development involves the growth of hierarchy. I showed that a simple model of hierarchy could explain why the number of managers increases with energy use. To get a sense for this model, try the app below. A web app showing how the growth of hierarchy leads to the growth of managers. Click the image to use the app.So as societies develop, they replace small-scale competition with large-scale hierarchy. In other words, economic development means killing the free market and replacing it with

Topics:

Editor considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from Blair Fix

In The Growth of Hierarchy and the Death of the Free Market, I argued that economic development involves killing the free market. What was the evidence? As energy use increases, so does the relative number of managers.

This growth of managers, I argued, indicates that economic development involves the growth of hierarchy. I showed that a simple model of hierarchy could explain why the number of managers increases with energy use. To get a sense for this model, try the app below.

So as societies develop, they replace small-scale competition with large-scale hierarchy. In other words, economic development means killing the free market and replacing it with central planning.

At the end of the post, I noted that the term ‘free market’ is often used in an Orwellian sense. Free-market advocates evoke pleasant images of entrepreneurs and small businesses. But the policies sought in the name of the ‘free market’ often benefit big business. So the term ‘free market’ is doublespeak for the unfettered power of large hierarchies. In the name of ‘freedom’, we’re actually concentrating hierarchical power.

This is an incendiary idea that deserves more investigation. In this post, I’m going to quantify the doublespeak nature of the term ‘free market’. I’ll show you that the less free market we have, the more we use the phrase ‘free market’. George Orwell would be proud.

Google Ngrams

Before diving into the analysis, I’ll talk about the tool that I’ve used to quantify word frequency. It’s called Google Ngram Viewer.

As part of its gluttonous appetite for data, Google has digitized millions of books. Using these books, Google has created a database of the frequency of words and phrases in the English language. They call it the ‘ngram’ database. Why? Because in linguistic jargon, a sequence of text is called an n-gram. Freely available, the ngram database is a gift to those interested in our changing language.

My only qualm with the Ngram Viewer is that it doesn’t allow you to download the data from a given search. But with a bit of finagling, you can get the data from your browser. Johannes Filter has a nice tutorial on how to do this.

Talking About the ‘Free Market’

Back to the analysis! Here I’ll use Google Ngrams to measure the frequency of the phrase ‘free market’. I’m going to compare this frequency to the growth of management in the United States.

Remember that the number of managers is our proxy for hierarchy. More managers means more hierarchy and less actual free market. To make the comparison to US data fare, I’ll look only at word frequency in American English.

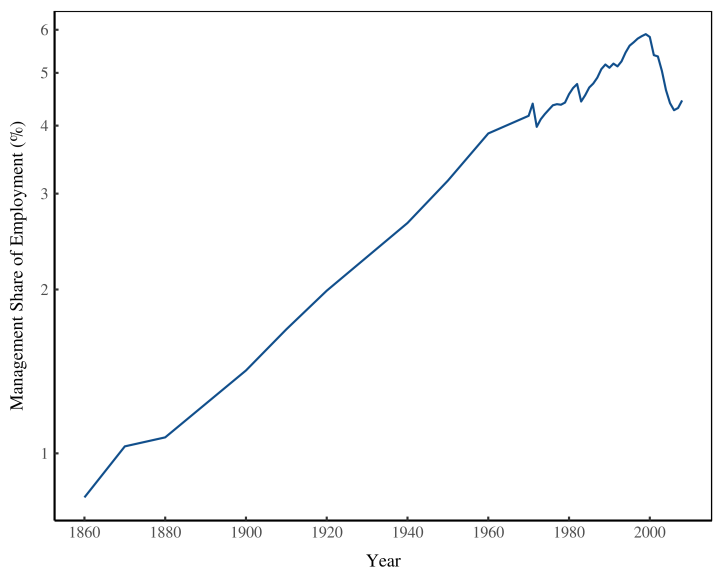

We’ll begin with the growth of management in the United States (Figure 1). The relative number of US managers grew continuously from 1860 to the late 1990s, before declining slightly in the 2000s. So for more than a century, the actual US free market declined and was replaced by hierarchical central planning.

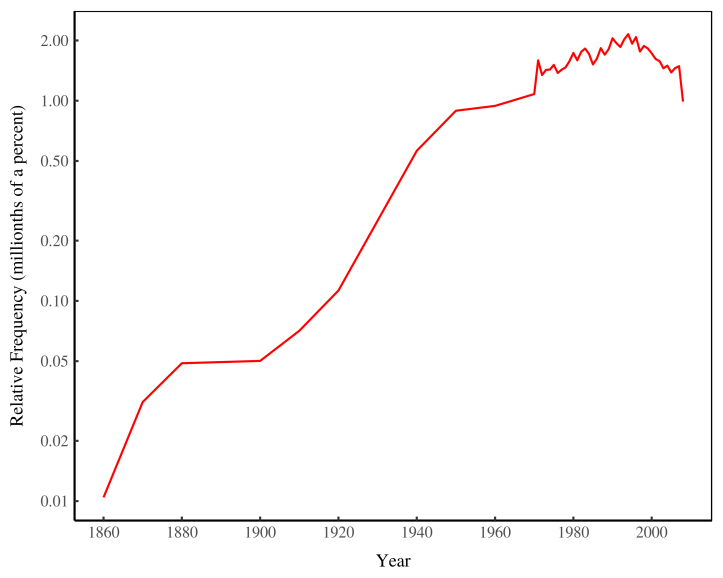

Now, you’d think that as the actual free market dies, we’d use the phrase ‘free market’ less. But it turns out that the opposite is true. In American English, the frequency of the term ‘free market’ grew continuously from 1860 to the 1990s, before declining slightly in the 2000s.

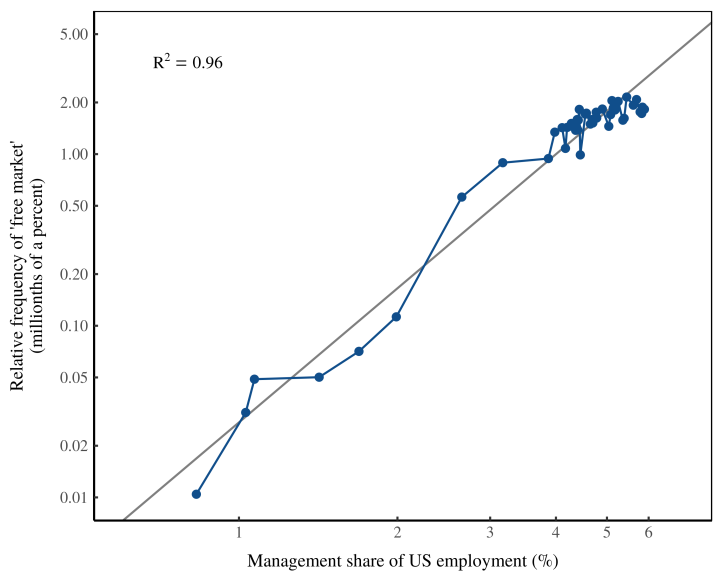

Does the trend in Figure 2 look familiar? To me it looks very similar to the trend in US management employment (Figure 1). Let’s look at the correlation between the two series. It’s pretty tight:

So as management employment increases, our use of the term ‘free market’ grows in lock step. In other words, we talk more about the free market as it dies.

I view the correlation in Figure 3 as a testament to the Orwellian nature of the term ‘free market’. It’s not about small-scale competition. Instead, the ‘free market’ is a euphemism for unfettered power. So the more we concentrate power, the more we talk about ‘free markets’.

Who’s talking about the free market?

Here’s an interesting thought. What if it’s the management class that is talking about the free market?

This would explain why the term ‘free market’ is tightly correlated with the relative number of managers. If most managers are free-market ideologues, the use of the term ‘free market’ should grow with the number of managers.

If this is true, the irony is palpable. Managers are essentially central planners, so their job is the farthest thing from the free market. If managers are spouting free-market ideology, it means the management talk doesn’t match the management walk.

This potential disconnect between what managers say and what they do is easy to imagine. It has a parallel in the economics profession. You’d be hard pressed to find a group of people who love the (idea of a) free market more than academic economists.

But ask yourself where academic economists work. Are they self-employed, selling their ideas on the free market? Of course not! They live in the ivory tower, a bastion of hierarchy and bureaucracy. Academic economists talk about the free market while working in an institution that is the furthest thing from it.

Lying and getting away with it?

I’ll conclude this foray into free-market doublespeak by quoting Edward S. Herman. In his book Beyond Hypocrisy, Herman writes:

What is really important in the … world of doublespeak is the ability to lie, whether knowingly or unconsciously, and to get away with it …

If my theory above is correct, then the management class is collectively lying to us. They talk about the ‘free market’ as they increase hierarchy. And it seems, in large part, that they have gotten away with it.