Is it possible to model unemployment in neoclassical ‘DSGE’ macro-economic models ? I’m occupied with a project which compares neoclassical macro concepts with statistical macro concepts. One of the glaring differences between the statistics and the models: we measure unemployment as a matter of routine but DSGE-models do not conceptualize or define, let alone operationalize it. When you model our society as a one person ‘Robinson Crusoë’ ‘society’ you will have somebody who works a little less or more but who will never be entirely unemployed. Models with heterogeneous agents have problems with this, too. On twitter, Lukas Freund however pointed me however to the 2018 article ‘Unemployment (fears) and deflationary spiral’ by Wouter J. den Haan, Pontus Rendahl and Markus Riegler, which

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

Is it possible to model unemployment in neoclassical ‘DSGE’ macro-economic models ? I’m occupied with a project which compares neoclassical macro concepts with statistical macro concepts. One of the glaring differences between the statistics and the models: we measure unemployment as a matter of routine but DSGE-models do not conceptualize or define, let alone operationalize it. When you model our society as a one person ‘Robinson Crusoë’ ‘society’ you will have somebody who works a little less or more but who will never be entirely unemployed. Models with heterogeneous agents have problems with this, too. On twitter, Lukas Freund however pointed me however to the 2018 article ‘Unemployment (fears) and deflationary spiral’ by Wouter J. den Haan, Pontus Rendahl and Markus Riegler, which does model unemployment.

Does this article require me to rewrite my stuff on ‘labor’? Nope. To be able to model unemployment they do not (yet) put a silver bullet through the heart of the models. But they do cut out its liver.

What do I mean? Central to DSGE models is the ‘Euler equation’ which relates present consumption to consumption yet to come. The basic intuition behind this formula (not the formula itself) is:

U = C-N

Or: Social Utility is Utility of total consumption minus Disutility of total labor. Consumption is gain, labor is pain. The idea is rather vaguely defined. Social Utility is not well-defined (if at all), consumption as a rule excludes government products and services like education and law and order and bridges and often, hours and persons are not well distinguished or a vague , sub-scientific description like ‘labor services’ is used for labor. Also, consumption and labor are recalculated into ‘utility’ without clear-cut deep, sound, fundamental parameters like Avogadro’s number. Never mind. Even in this fuzzy environment it is difficult to model unemployment, as increasing unemployment is supposed to diminish pain. While it, as we all know, it increases pain. There is a momentous literature about this, even when people like Thomas Sargent and Robert Lucas and Edward Prescott and Christopher Pissarides, al winners of the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Honor of Alfred Nobel, all use the word ‘leisure’ when they mean ‘unemployment’.

So, what do Den Haan, Rendahl and Riegler do? Brilliant. They cut out N. The basic formula at the heart of all DSGE models is fundamentally altered. This is a paradigm shift. As they state it: ‘there is neither home production not any disutility from working’. In a sense they are following Keynes with this and unlike labor markets in ‘normal’ DSGE models their labor market does not fit Keynes’ description of the theory of ‘classical’ labor market models in chapter 2 of the General Theory (it’s not a new paradigm shift) and is much closer to a Keynesian labor market as well as unemployment as we measure it. In the project I state that ‘labor’ and to be precise wage labor is the core of the ‘macro battles’. This corroborates this idea. Thanks!

How about the rest of the article? Some remarks:

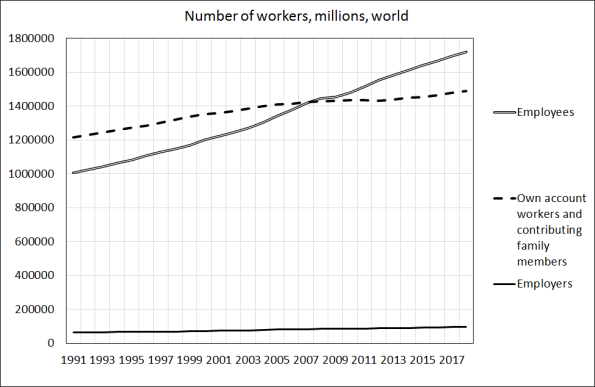

The model is not about a modern economy. Part of the trick used to model unemployment is assuming: ‘there is one worker attached to each active firm’. As, every period, some firms go bust and as it takes time to establish a new one, there will, hence, also be unemployment. And even cyclical swings in unemployment when for whatever reasons in one period more firms go bust than usual and you put in a positive feedback loop between the amount of firms going bust and whatever parameter you have which influences the amount of firms which going bust. Unemployment will go down as new firms will be established. To estimate the number of new firms created they use ‘search theory’: the less firms there are, the easier it gets to establish one and the more unemployed there are, the faster this will happen, even when the model has the useful addition that creating a firm requires capital, too. This, however, is not a description of our present day wage labor economy but a nostalgic but modernist description of the handicraft economy of the pre-industrial village or, less benign and closer to the model (which assumes that there is only one product) the mass production of textiles or other consumer goods in poor and often destitute households in the countryside in eighteenth and nineteenth century Europe. From Engels to Marx to Veblen to Means to Keynes to Coase to Robinson to Galbraith to Lee to Keen economists have been shouting at the top of their lungs to neoclassicals: ‘Hey guys, even when own account workers are still very important we’re basically having a wage labor economy now with monopsonic labor markets and large companies, centralized control and with administered prices defined in long-term value chain contracts as well as positive economies of scale… Live with it’. Assuming everybody is self-employed, as the article does, is not an apt description of our international value chains Walmart administered prices economy.

Graph 1. Number of workers world wide, divided into three classes. Source: ILO.

Aside: two very good studies about the establishment of seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth cottage industries are Ogilvie, Küpker, and Maegraith (2012), “Household Debt in Early Modern Germany: Evidence from Personal Inventories”, and Pfister (2007), “Rural land and credit markets. The permanent income hypothesis and proto-industry: evidence from early modern Zurich” and for the Netherlands: Zuijderduijn, Moor and Van Zanden, “Small is beautiful. On the efficiency of capital markets in late medieval Holland”. All these studies show that institutions evolved which guarantee that households could lend to set up shop or save/invest for old age. Fun fact: the Ogilvie e.a. households with a milk cow had hoarded less cash than households without one, which gives the phrase ‘cash cow’ its original meaning back.The model suffers from a common failures of DSGE models: ‘there is no financial intermediation’ i.e. no banking sector. This, too, is representative of eighteenth and nineteenth country villages. Also: the monetary asset ‘serves as the unit of account’. No. A unit of account is attached to a monetary asset but you can’t equate it with it. In a sense, as there is a central bank the sector banks is included in the sector households.

There are too many neoclassical platitudes like: “Karsrud e.a. report that the amount of consumption that is financed out of an increase in debt actually decreases following a displacement [getting unemployed, M.K.]”. Yeah. When somebody cuts of my leg I can’t walk as fast anymore… In the neoclassical world, this seems to be a surprise as people are infinitely lived and will, eventually, be able to pay off the debt. ‘Where I find myself pointing out to economists that people do not live forever’.

The definition of unemployment used is interesting. It is not equal to the definition as used by statistical institutes *all over the world* which is remarkable as they do use this official rate for comparison. The official definition is based on individual persons, not on households. The definition of the model is however based upon households (highly interesting!). Which means that they have to exclude quite a chunk from the economy. A large EU household survey is used (good!) but they exclude quite some households:

Excluded Households. To ensure that the data are used resemble the households of our model, we exclude types on agents that are not present in our model. In particular, we apply the following filters:

- Always exclude the entire household if any household member is (according to PE0100a)

- #2 (sick/maternity leave),

- #5 retiree or early retiree,

- #6 permanently disabled,

- #7 compulsary military service, and

- #9 other not working for pay.

- Always exclude the entire household if nobody in the household is

- either #1 (employed) or #3 (unemployed).

- Exclude the entire household if there are more than two people either employed or unemployed.

- Exclude the entire household if any in the household is aged 65 years or higher.

- Exclude the entire household if nobody is aged 20 years or older.

- Exclude individuals without reported labor force status.

I would have loved to see a more thorough comparison of these data with the official statistics.

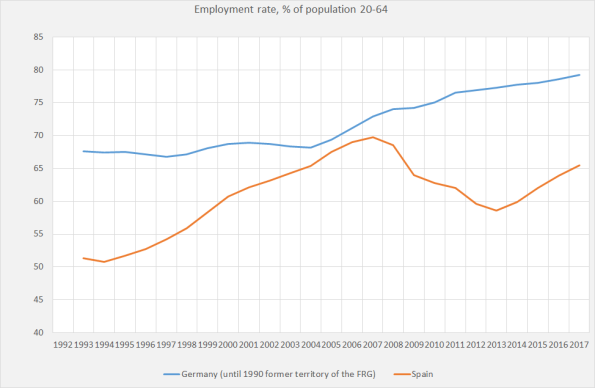

They add the unemployment rates of France, the UK, Germany and Spain together, even when labor markets in these countries behaved differently which might lead to fallacies of composition while they also do not pay attention to differences between changes in hours per job and changes in unemployed persons; after 2008 average hours per person working declined quite a bit in Germany, which must have mitigated the increase in unemployment with somewhere between 2,5 and 3.5percentage points, but not in Spain. Using search theory requires one to look at labor market flows which forces one to include people outside the labor market as net new entrants are quite important when it comes to changes in unemployment (even when changes in the total number of jobs are hardly affected). This is not part of the model. For the elephant in the room: see the graph. How smart is it to take an average of these countries?

Graph 2. Unemployment in Spain and Germany. Source: Eurostat.

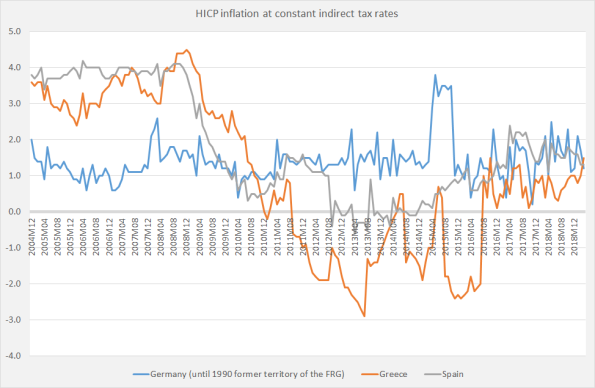

A general equilibrium approach is used which means that, in the end, unemployment will be zero (aside from friction unemployment) even when what Keynes called ‘involuntary unemployment’ seems to exist (basically, unemployment which is not solved by lower real wages). Important is however that they realize that increases in employment during expansions are slower than reductions during crises (graph). In reality, however, job finding rates of the unemployed do not always go down during crises even when job finding rates of new entrants and, later, long-term unemployed do. Meaning that during a crisis, unemployment and inactivity themselves become a friction, hampering the decline of unemployment. Even then, job finding rates do not explain unemployment, changes in the amount of jobs relative to the total labor force do. I’m also not too happy with their idea that “a reduction in the price level that actually goes together with an increase in expected inflation and substantial decrease in the [expected?, M.K.] real interest rate”. In a general equilibrium world, a temporary decrease of the price level will be counteracted by higher inflation tomorrow. This is not what happened in Spain (or Greece). Price levels decreased, but inflation is still lower than it used to be even when the price level is still way below the German level. By the way: Greece and Spain are examples of involuntary unemployment in the sense of Keynes in chapter 2 of the General Theory.

Graph 3. HICP inflation and constant tax rates. Source: Eurostat.

Some other quibbles:

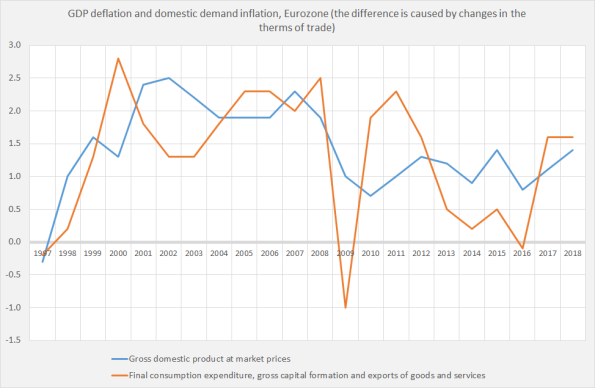

The authors use the GDP deflator. As this is influenced by the terms of trade (as I show here) they should have used the domestic demand plus export deflator (graph). 2013-2016 clearly was a low inflation period, unlike 2017-2018, total difference over this period is about 3 to 4% which is – a lot (as can be seen, inflation has rebounded after the 2012-2016 ‘double dip’, something not entirely unimportant but not visible in the GDP deflator data). I leave it to the authors to do the arithmetic, but as domestic demand plus export prices are more volatile than GDP prices, they might enable better testing of the model.

Graph 4. Different macro-deflators. Source: Eurostat.

The authors use RULC: real unit labor costs or nominal labor costs per real unit of output. On the macro level, this variable is prone to a whole array of fallacies of composition, as I show here. Basically: you can’t assume that GDP, a historical aggregate monetary variable, is one unchanging physical product.

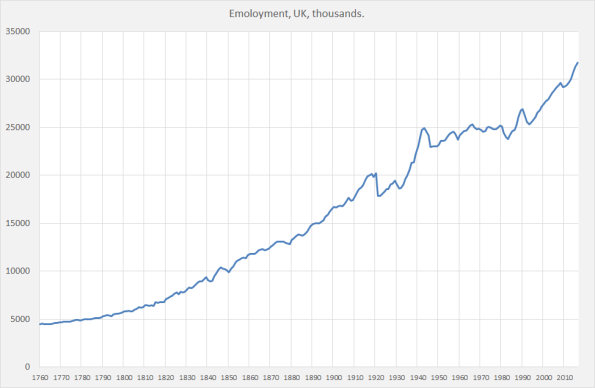

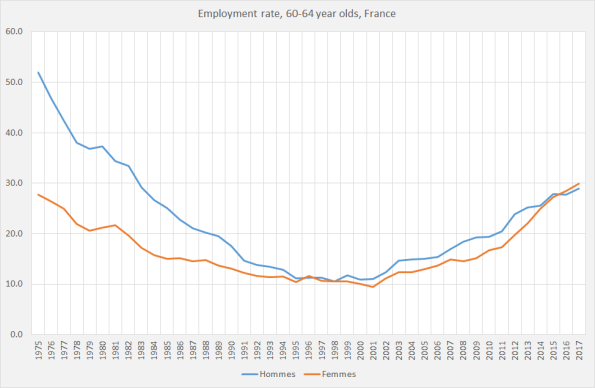

The authors state that there are only relatively short (OECD) series for employment, starting in 1980. Finding and comparing sources is part of craft of being a macro-economists. Longer series exist, for all the countries mentioned, here only one (graph) (Wow: never realized that it was only after 1985 that the UK really surpassed WWII employment… Another wow: the female 60-64 employment rate in France is higher than the male employment rate).

Graph 5. Long term employment, UK. Source: Bank of England.

Graph 6. Employment rates in France. source: INSEE.

Long term data for Germany here. Data for Spain on ‘trading economics’ already show longer series than back to 1980. This is the direction macro is going, join the pack.

A HP filter is used to calculate trends. This method has been discredited.

As stated: cutting out N is wonderful – the baby can finally be put in the tub. But there still is some bathwater which has to be thrown out. Introducing wage labor and replacing social utility with transactions based variables might be the next steps. A famous economist, what’s his name again, once did this already…