From Geoff Davies The need for a new start in economics arises regularly on this blog site, for example: Economics — enslaved by the wrong theory And here is an edited extract addressing this issue from my book Economy, Society, Nature.. The point is not that ‘complexity’ gives rise to another ‘school’ of economics, but that it provides a general framework that accords with observations and is capable of accommodating many existing schools, but not all. Many of the ideas presented here have been around for some time but the subject has been in some confusion, with a tendency still, among dissenting economists, to think of ‘schools’ of thought and to promote a ‘pluralist’ approach. Whereas it is laudable to consider a wide range of ideas, rather than the sterile monoculture of

Topics:

Editor considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from Geoff Davies

The need for a new start in economics arises regularly on this blog site, for example: Economics — enslaved by the wrong theory And here is an edited extract addressing this issue from my book Economy, Society, Nature.. The point is not that ‘complexity’ gives rise to another ‘school’ of economics, but that it provides a general framework that accords with observations and is capable of accommodating many existing schools, but not all.

The need for a new start in economics arises regularly on this blog site, for example: Economics — enslaved by the wrong theory And here is an edited extract addressing this issue from my book Economy, Society, Nature.. The point is not that ‘complexity’ gives rise to another ‘school’ of economics, but that it provides a general framework that accords with observations and is capable of accommodating many existing schools, but not all.Many of the ideas presented here have been around for some time but the subject has been in some confusion, with a tendency still, among dissenting economists, to think of ‘schools’ of thought and to promote a ‘pluralist’ approach. Whereas it is laudable to consider a wide range of ideas, rather than the sterile monoculture of mainstream neoclassical economics, the result has still lacked coherence. For example, the recently issued book Rethinking Economics has chapters on Post-Keynesian, Marxist, Austrian, Institutional, Feminist, Behavioural, Complexity, Co-operative and Ecological Economics2 but little about how the various conceptions might relate to each other.

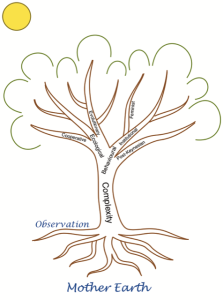

The present book argues for a natural relationship among these approaches that brings coherence to plurality. The new conception identifies complexity as the trunk of a tree, with many of those schools as main limbs – see Figure 1.1. However not all schools belong with this new species.

Figure 1.1. A tree metaphor relating economic approaches. Complexity forms the trunk and the limbs are various schools that are compatible with the self-organising conception of modern economies. The labels are merely indicative, not definitive. The roots gather observations and are integral to the whole. The whole is nurtured by Mother Earth and energised by Grandfather Sun, as the Yuin people of my region refer to him.

The starting concept is of a self-organising system that is far from equilibrium. Such a system can give rise to complexity, a technical term that will be developed later. The behaviour of a self-organising system depends critically on the way in which information is passed among its components. Within an economic system there are two main signalling processes – social interaction and money. Thus both social interaction and money take a central place in this conception, whereas both have been largely excluded from neoclassical economics.

We can ask the fundamental questions also of money and people. What is the nature and the purpose of money? What is human nature? We know far more about people than was known when neoclassical economics was formulated. Money has been the subject of great confusion, but it can be understood by returning to simple situations and concepts: money is a social contract and a medium of exchange. From these core ideas a broad understanding of modern economies can be built up.

As important as its ability to subsume some existing schools of economics, the new conception is based in observations, and capable of accommodating many further observations. For example it acknowledges that economies of scale are pervasive and it can accommodate a market crash, which the mainstream neoclassical theory cannot.

The conception offered here is a sketch, an approach, not a fully worked out theory. Switching metaphors, the main landmarks and features of a new territory are described, but much remains to be explored. However it offers a far more productive starting point than neoclassical theory.

A comprehensive economic ‘theory of everything’ will not emerge soon, if ever, but much useful understanding can be gained in the meantime. Physicists in the nineteenth century thought they had assembled a clockwork theory of everything, covering mechanics, gravity, electro-magnetics, heat and so on. However troubling, inconsistent observations caused them eventually to replace that vision with the radically different ideas of quantum mechanics and general relativity. To this day there is no comprehensive ‘theory of everything’ because no-one knows how to reconcile the very small (quantum mechanics) with the very large (relativity). This has not prevented enormous advances in useful understanding.