From David Ruccio How else to put it? The levels of economic inequality in the United States are obscene. According to the latest data from the World Inequality Database, the share of pre-tax income captured by the top 1 percent of Americans is an astounding 20.1 percent, while the bottom 50 percent are forced to make due with only 12.6 percent. And the distribution of wealth is even more unequal: the top 1 percent own 37.2 percent but the bottom 50 percent of Americans hold no net wealth at all. And, if present trends continue—with corporate profits growing and the Trump administration in power—economic inequality is only going to get worse. It’s no wonder, then, that Dani Rodrick argues that the Democratic Party will face a critical test in the next U.S. presidential election:

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

How else to put it? The levels of economic inequality in the United States are obscene.

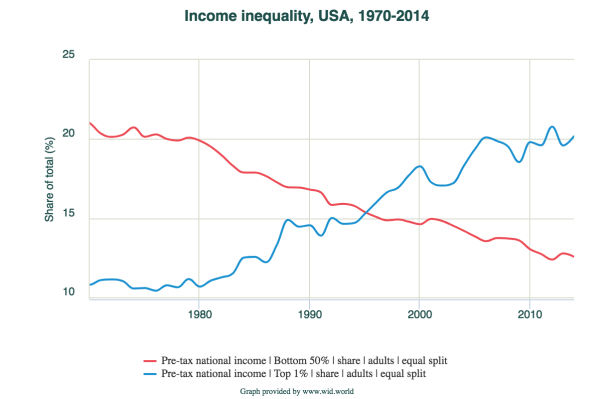

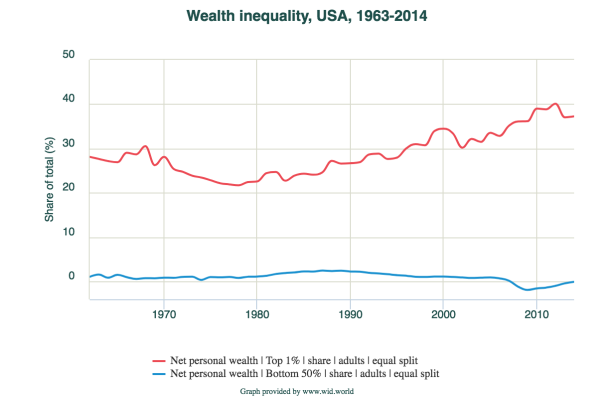

According to the latest data from the World Inequality Database, the share of pre-tax income captured by the top 1 percent of Americans is an astounding 20.1 percent, while the bottom 50 percent are forced to make due with only 12.6 percent. And the distribution of wealth is even more unequal: the top 1 percent own 37.2 percent but the bottom 50 percent of Americans hold no net wealth at all.

And, if present trends continue—with corporate profits growing and the Trump administration in power—economic inequality is only going to get worse.

It’s no wonder, then, that Dani Rodrick argues that the Democratic Party will face a critical test in the next U.S. presidential election:

Will it remain the party of merely adding sweeteners to an unjust economic system? Or does it have the courage to address unfair inequality by attacking it at its roots?

Clearly, Rodrick reflecting on the poor showing of Hillary Clinton in the last presidential election, who promised to continue the policies of economic recovery under Barack Obama, and the fact that most of the proposals currently on the table are aimed at raising taxes on the rich. They don’t really get at the roots of the grotesque levels of inequality the U.S. economy has been generating.

The problem is, most of what Rodrick offers as an alternative agenda for “the Left” also fails that test. His plan for “inclusive prosperity” is confined to “productive re-integration of the domestic economy” (basically, encouraging large corporations to invest in their local communities), directing technological change (to help less-skilled workers), rebalancing labor markets (for example, by promoting unionization and raising minimum wages), regulating the financial sector (with higher capital requirements and tighter scrutiny), and electoral reform (such as more stringent campaign financial rules).

Now, there aren’t many on the Left—at least progressive thinkers and activists I talk to or whose work I read—who would be opposed to such changes. They would, indeed, improve the condition of the working-class and make it somewhat easier for the vast majority of Americans to make their voices heard.

But, by the same token, the kinds of policies Rodrick is putting forward do not meet his own test of attacking the problem of inequality “at its roots.”

The fact is, inequality begins where the surplus is produced and appropriated—in the factories, offices, and warehouses where most Americans work. Workers produce much more value than they receive in the form of wages and salaries, and it’s that surplus that is appropriated by their corporate employers to do with it what they will. Some of it is invested and the rest is distributed for other purposes—stock buybacks, mergers and acquisitions, salaries for corporate executives, and so on—which only serve to make the existing distribution of income and wealth even more unequal.

In other words, it’s that control over the surplus by a small minority of Americans that is the root, the condition or source, of the unfair inequality that characterizes the United States today. And there’s nothing in Rodrick’s set of policies that seeks to fundamentally alter or solve that particular problem.

Perhaps a month ago, when Rodrick first published his piece, he could claim to have been out front in the discussion—and perhaps he still is for mainstream liberals. But already the terms of debate, for the Left, have bypassed him and moved on. Now, politicians, activists, and journalists are asking new questions and posing new solutions—under the rubric of socialism.*

People in the United States often ask whether or not we should keep the socialist label. My answer is an unequivocal “yes,” for two reasons: one is that it ties contemporary discussions and debates to a long historical tradition of criticizing existing conditions and proposing alternatives; second, socialism is based on a recognition that the problems workers face are based on and stem from an “unjust economic system,” and “merely adding sweeteners” doesn’t represent a solution.

The current discussion of socialism is only in its infancy, and it’s impossible to tell at this point where it will end up. But already, in putting issues like a Green New Deal and economic democracy on the table, it is much close to attacking the roots of unfair inequality in the United States than anything mainstream Democrats or Dani Rodrick have to offer.

*Even “On Point,” a radio program produced by WBUR in Boston and broadcast every weekday on NPR stations around the United States, recently hosted an episode on socialism.