From David Ruccio On behalf of millions of young people striking on behalf of climate justice, 15-year-old Greta Thunberg excoriated world leaders for “moving forward with the same bad ideas that got us into this mess.” Our civilization is being sacrificed for the opportunity of a very small number of people to continue making enormous amounts of money. . . Until you start focusing on what needs to be done rather than what is politically possible, there is no hope. We cannot solve a crisis without treating it as a crisis. We need to keep the fossil fuels in the ground, and we need to focus on equity. And if solutions within the system are so impossible to find, maybe we should change the system itself. Much the same applies, of course, to the economic system that generates such

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

On behalf of millions of young people striking on behalf of climate justice, 15-year-old Greta Thunberg excoriated world leaders for “moving forward with the same bad ideas that got us into this mess.”

Our civilization is being sacrificed for the opportunity of a very small number of people to continue making enormous amounts of money. . .

Until you start focusing on what needs to be done rather than what is politically possible, there is no hope. We cannot solve a crisis without treating it as a crisis.

We need to keep the fossil fuels in the ground, and we need to focus on equity. And if solutions within the system are so impossible to find, maybe we should change the system itself.

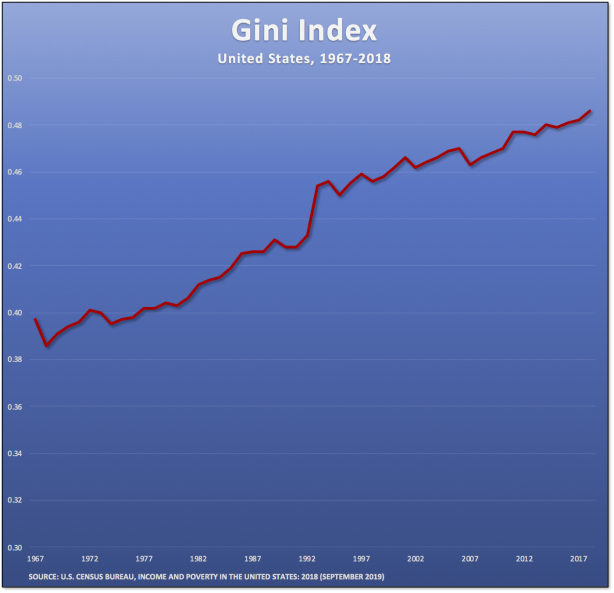

Much the same applies, of course, to the economic system that generates such grotesque levels of inequality. At the same time that Thunberg was making headlines in the United States and around the world, the U.S. Census Bureau reported that inequality—as measured by the Gini index for income—hit its highest level since the Census Bureau started tracking it more than five decades ago.

I’ve compiled the numbers in the chart at the top of the post. In 1967, the Gini index stood at 0.397; as of last year, it had risen to 0.486. In other words, income inequality had grown by more than 22 percent during that period.

As I warned back in 2014, Gini coefficients should be used with more than a few grains of salt. First, they should never be used to compare degrees of inequality across countries. Second, because the Gini boils down the overall distribution of income to a single number, it loses some detail. For example, if the Gini coefficient has gone up, it doesn’t tell us whether this is because the share going to the bottom 90 percent went down or the top 1 percent (or, for that matter, the top 0.1 percent or the top 0.01 percent) went up.

So, we need to look at the actual income shares for various percentiles of the U.S. population to find out why inequality has grown so spectacularly since the late 1960s.

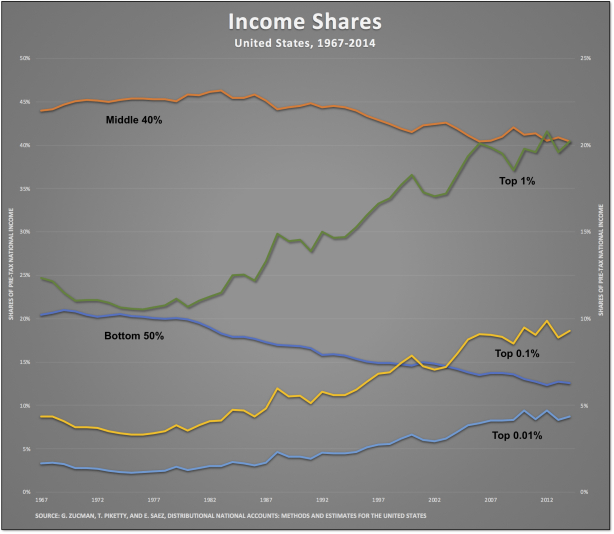

As is clear from the chart above (which, given the availability of data, ends in 2014), while the share of income going to the middle 40 percent (the orange line) did in fact decline (from 0.44 to 0.40), those in the bottom 50 percent (dark blue) were the real losers (as their share declined from an already low 0.20 to just 0.13). And at the top? The shares of the surplus captured by all of them—the top 1 percent (green, from 0.12 to .20), the top 0.1 percent (yellow, from 0.04 to 0.09), and the top 0.01 percent (light blue, from 0.02 to 0.04)—increased in what can only be described as an obscene manner.

The conclusion is therefore obvious: the rise in the Gini coefficient in the United States does reveal a long-term shift in the distribution of income from those at the bottom to a tiny group at the top.

And, yes, as Thunberg has correctly noted, if solutions within the system are so impossible to find, it’s time to change the system itself.