From David Ruccio Across American universities, corporations, and financial institutions, researchers are honing computer models designed to predict the winner in the November 2020 presidential election in which Donald Trump will face a Democratic candidate still to be determined. One such set of models, developed by Moody’s Analytics, which focuses on the electoral college (and not the national popular vote), predicts a convincing victory for Trump. Moody’s based its projections on how consumers feel about their own financial situation (the so-called pocketbook model), the gains the stock market has achieved during Trump’s time in office (the stock-market model), and the prospects for unemployment (the unemployment model).* As I see it, there are two fundamental problems with

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

Across American universities, corporations, and financial institutions, researchers are honing computer models designed to predict the winner in the November 2020 presidential election in which Donald Trump will face a Democratic candidate still to be determined.

One such set of models, developed by Moody’s Analytics, which focuses on the electoral college (and not the national popular vote), predicts a convincing victory for Trump. Moody’s based its projections on how consumers feel about their own financial situation (the so-called pocketbook model), the gains the stock market has achieved during Trump’s time in office (the stock-market model), and the prospects for unemployment (the unemployment model).*

As I see it, there are two fundamental problems with models like those used by Moody’s Analytics. First, they are based on the presumption that economic outcomes determine individual voting behavior (what is otherwise known as economic determinism). Such models exclude many other possible motivations or concerns for voters, including class notions of fairness and justice.** Second, the outcomes are predicated on a rosy picture of the U.S. economy, as measured by personal finances, the stock market, and the unemployment rate.

Things look quite different if we focus on an alternative narrative of the U.S. economy, which in turn can lead voters to think and act based on a sense of unfairness or injustice (alongside and combined with all their other reactions to the different political campaigns and candidates).

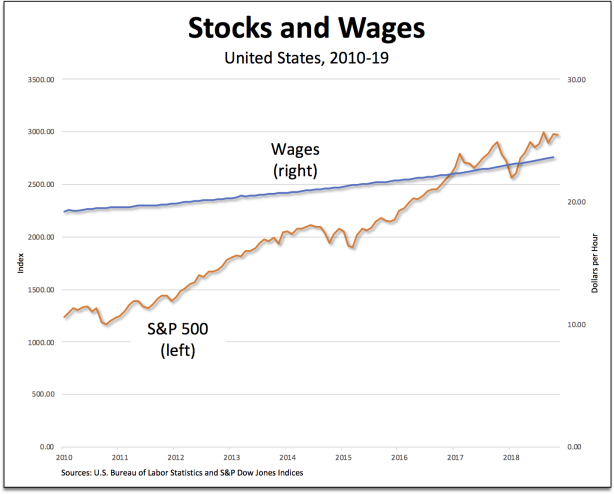

Consider, for example, what’s happened to stocks and wages—both under Trump and in a longer time horizon. Since the beginning of 2017, workers’ wages (as measured by the average hourly earnings of production and nonsupervisory employees, the blue line in the chart above) have risen by only 8.4 percent while the stock market (illustrated by the S&P 500 index, the orange line) has increased in value by more than 30 percent.*** Clearly, in recent years American workers have been falling further and further behind the small group of wealthy individuals and large corporations at the top of the U.S. economic pyramid. Going back to 2010, the difference is even greater: hourly wages are up a total of 23 percent while stocks have soared by 140 percent. These differences represent an indictment of the fundamentally uneven recovery from the Second Great Depression under both Barack Obama and Trump.

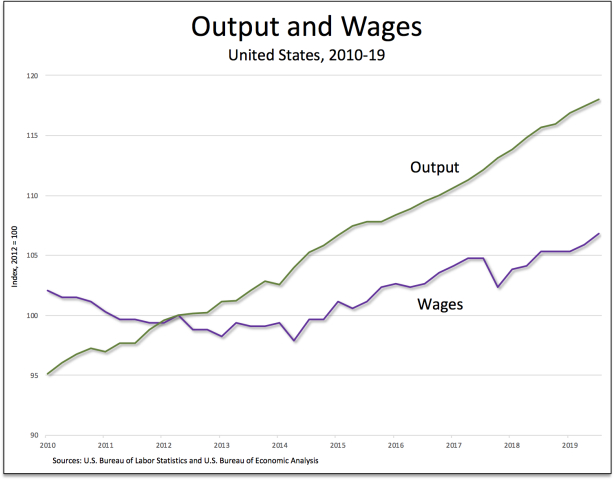

A similar picture emerges if we factor out inflation and compare workers’ real wages and the real output they produce. Since Trump took office, there’s been a growing gap between real Gross Domestic Output (the green line in the chart above, which has increased by 6.5 percent) and weekly wages (the purple line, which are up only 2.5 percent). Again, the gap is even more dramatic if we go back to early 2010: wage increases amount to less than one fifth the growth in output. It is evident that, in both cases, the U.S. economy has been growing at the expense of the nation’s workers—to the benefit of large corporations and wealthy individuals.

According to this class narrative of the U.S. economy, American workers have been losing out relative to their corporate employers and a small group of individuals who are sharing in the spoils of a decidedly unfair and unjust set of economic policies and institutions. That’s been the case while Trump has been in office as well as for many years before that. The Fed can continue cutting interest rates (as it did last week, for the third time this year) but it won’t change the grotesquely uneven class dynamic of the U.S. economy.

That’s why Carolyn Valli, executive director of the Central Berkshire Habitat for Humanity, found it necessary to declare at a recent Fed Cleveland event that “It doesn’t feel like a boom yet.” Not under Trump nor with his predecessor.

The Moody’s Analytics models may predict a victory for Trump over a generic Democratic candidate but the class narrative I’ve outlined here leads to a very different scenario—a rejection of business as usual both within the Democratic Party, with the choice of a more left-wing economic populist presidential candidate, and in the general election, when the actual class content of Trump’s administration can be unmasked and ultimately defeated.

*The three models show Trump getting at least 289 electoral votes, assuming average voter turnout. His chances, of course, decrease with increased turnout on the Democratic side.

If turnout next year were historically high, Moody’s said, the Democratic candidate could win Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania – states that narrowly voted for Trump in 2016 and which are currently experiencing a manufacturing slowdown. In that scenario, the Democratic candidate would win with 279 electoral votes to Trump’s 259, Moody’s said.

**This approach to forecasting reminds me of John Howard Hermann (played by Max Baker) in the Coen brothers’ 2016 comedy Hail, Caesar!:

See, if you understand economics, you can actually write down what will happen in the future, with as much confidence as you write down the history of the past. Because it’s science. It’s not make believe.

***As Neil Irwin recently explained, more people may be working “but employers are not having to increase compensation much to recruit and retain people.” This trend challenges mainstream economic models and policy, according to which the relatively low unemployment rate should mean that workers are scarce and employers should need to start paying them more. And that’s not what’s happening. In fact, the opposite is occurring: employment is growing but the rate of increase of workers’ wages is actually declining.