From Blair Fix Let’s talk sustainability. Unless you’re an anti-science crank, you probably agree that we’ve got a problem with carbon emissions. We need to drastically cut emissions to avoid catastrophic climate change. On this we should all agree. The question that’s open for debate is how to cut emissions. I think we actually know very little about how do to this. But even worse than knowing little is thinking we know a lot when we don’t. As the old saying goes, “It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.” This post is about false solutions to climate change. These are ideas that seem like plausible ways to reduce carbon emissions, but that fall apart when we look at the evidence. If we’re serious about sustainability,

Topics:

Editor considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from Blair Fix

Let’s talk sustainability. Unless you’re an anti-science crank, you probably agree that we’ve got a problem with carbon emissions. We need to drastically cut emissions to avoid catastrophic climate change. On this we should all agree.

The question that’s open for debate is how to cut emissions. I think we actually know very little about how do to this. But even worse than knowing little is thinking we know a lot when we don’t. As the old saying goes, “It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

This post is about false solutions to climate change. These are ideas that seem like plausible ways to reduce carbon emissions, but that fall apart when we look at the evidence. If we’re serious about sustainability, we need to abandon ideas that won’t work.

This may seem obvious. But sustainability advocates sometimes forget that we need to test our ideas against evidence. Driven by the urgent need for action, some people latch on to a ‘solution’ and become fervent advocates for this course of action. They forget that their ‘solution’ may be wrong. We owe it to ourselves to keep a cool head and avoid this mistake. Future generations will thank us.

Here I’ll focus on one false solution to climate change. I’m going to debunk the idea that a service transition can reduce carbon emissions.

Why a service transition seems like a good way to reduce carbon emissions

A service transition seems like a good way to reduce emissions. Why? Because services use less energy than industrial sectors. So if we grow the service sector (and shrink industrial sectors), we should reduce our use of energy, and thereby reduce carbon emissions.

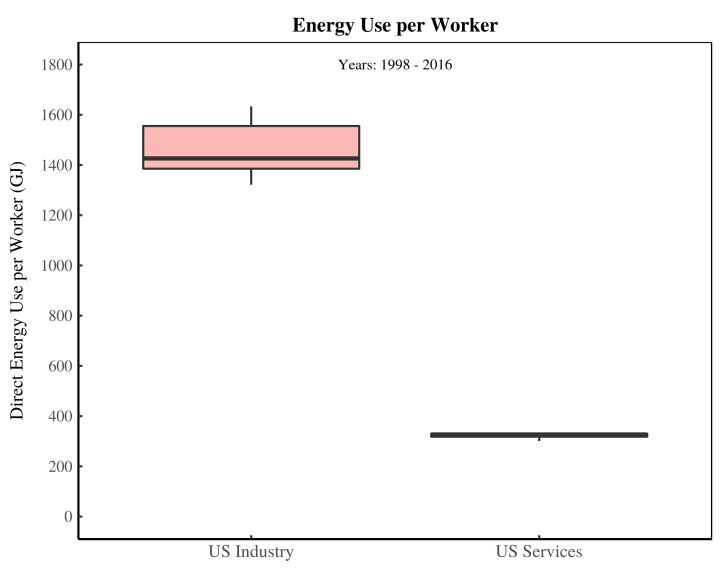

On the face of it, this reasoning seems sound. There’s overwhelming evidence that the service sector uses less energy than industry. Figure 1 shows data from the United States. Over the last 20 years, the US service sector used about 4 times less energy per worker than industry:

Given the evidence in Figure 1, it seems obvious that a service transition should reduce emissions. But it turns out that a service transition actually increases carbon emissions.

Transitioning to services: a recipe for increasing carbon emissions

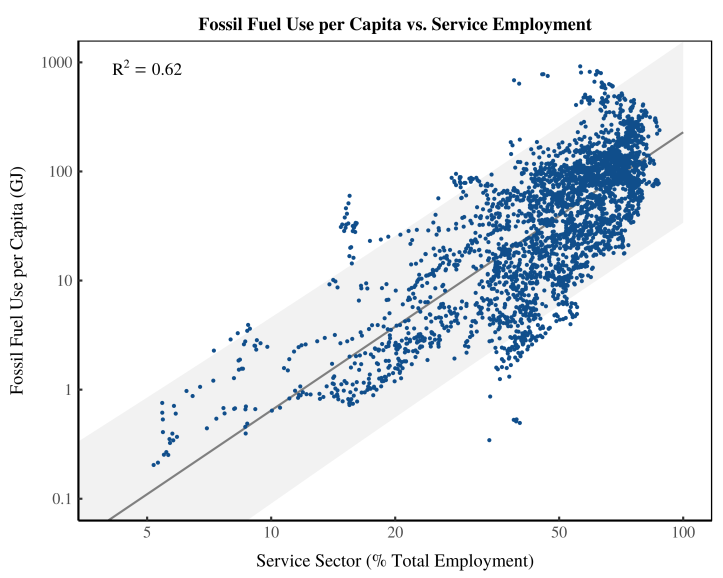

We’re going to look at how fossil fuel use and carbon emissions change as the service sector grows. To get the widest possible evidence, we’ll look at trends between all the countries of the world.

Let’s start by comparing fossil fuel use per person to the employment share of the service sector (Figure 2). It’s obvious here that a service transition leads to more fossil fuel use:

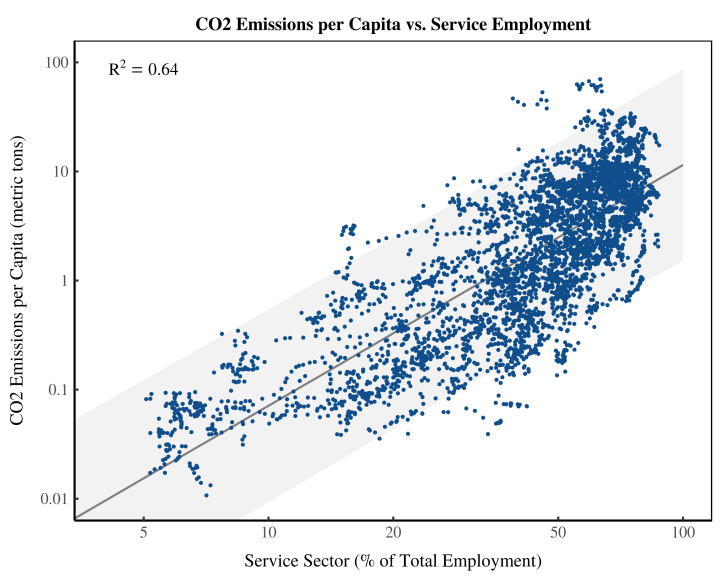

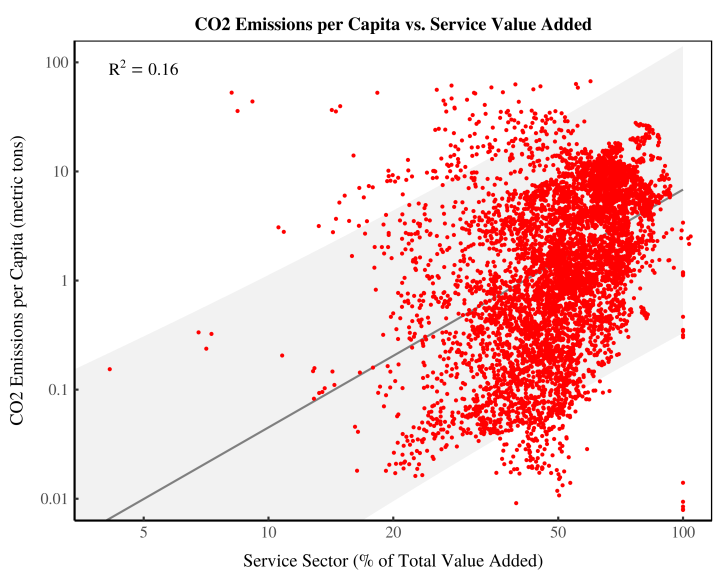

Unsurprisingly, carbon emissions per person also increase as service employment grows (Figure 3):

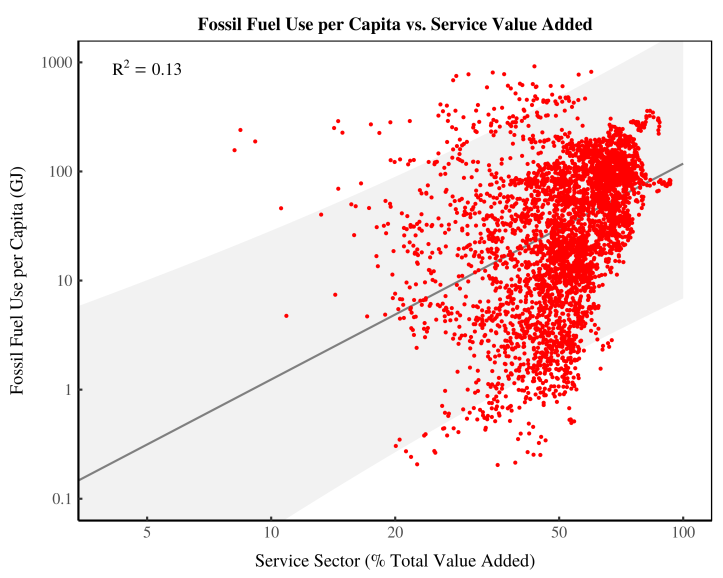

In Figures 2 and 3, we used employment share to measure the size of the service sector. We can also measure the size of the service sector using its share of value added. We still find the same trend. Figure 4 shows that as the service sector’s share of value added grows, so does fossil fuel use:

Figure 5 compares carbon emissions to the service sector’s share of value added. Again, no sign of emissions relief with a service transition:

The evidence is unequivocal. A service transition fails to reduce emissions. The question is — why?

The service transition: what goes wrong?

We have a paradox on our hands. The service sector uses less energy than industry, so it seems like a service transition should reduce carbon emissions. And yet we find that a service transition actually increases emissions. So what goes wrong?

The flaw in our reasoning is subtle, but devastating. We took evidence at a point in time (the lower energy use of services) and inferred a trend over time (that a service transition would reduce emissions). But in our haste, we forgot something key. We forgot about social change!

Here’s the crux of the problem. When societies transition to services, their structure doesn’t remain the same. Instead, the whole society transforms. People move to cities, businesses use different technology, consumption patterns change, and so on.

I could write a book-length post about the social changes that come with a transition to services. But here I’ll boil it down to something simple. A service transition is a recipe for economic growth.

Interestingly, this is not a new idea. More than 70 years ago, Colin Clark argued that a service transition is a key part of economic growth:

[T]he most important concomitant of economic progress [is] the movement of working population from agriculture to manufacture, and from manufacture to commerce and services. (Colin Clark, 1940)

Now here’s the thing about economic growth: it takes energy. Tim Garrett uses the analogy of a growing child. Why do children eat so much? Because they’re growing, and growing takes energy. The same is true of an economy. Producing stuff takes energy. And producing more stuff takes more energy.

Given this fact, we need to rethink the service transition. If a service transition is a recipe for economic growth, it’s also a recipe for using more energy. Let’s look at the evidence.

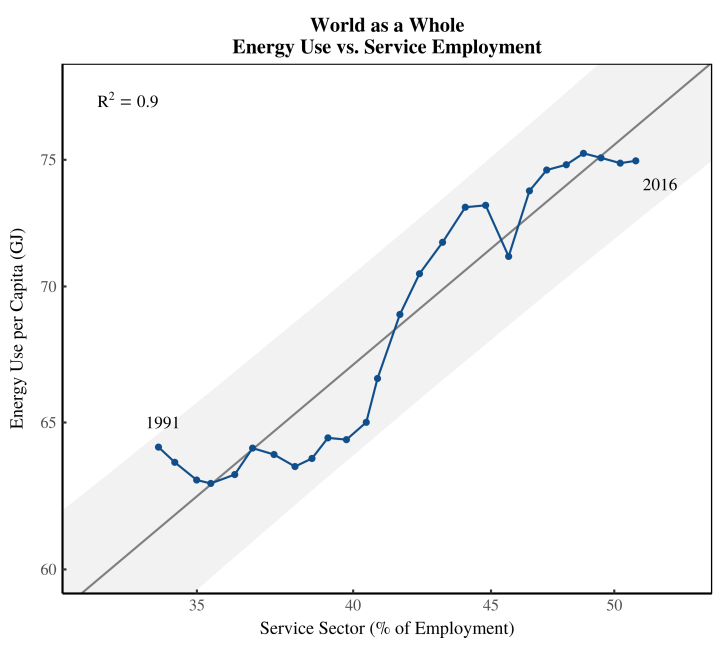

Figure 6 shows data for the world as a whole. As the service sector grows, so does energy use per person:

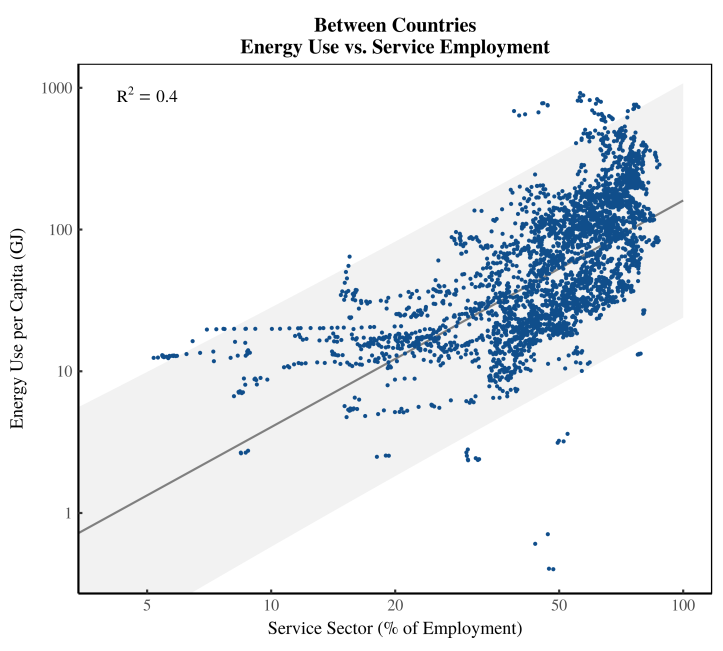

Figure 7 shows data for all the countries of the world. Again, as the service sector grows, so does energy use per person:

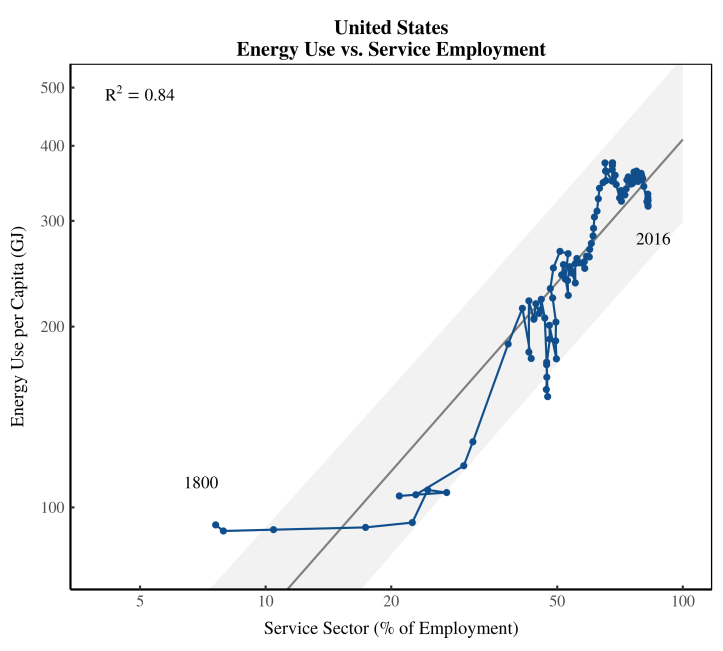

Figure 8 shows two centuries of US data. Again, no surprises. As the service sector grows, so does energy use per person:

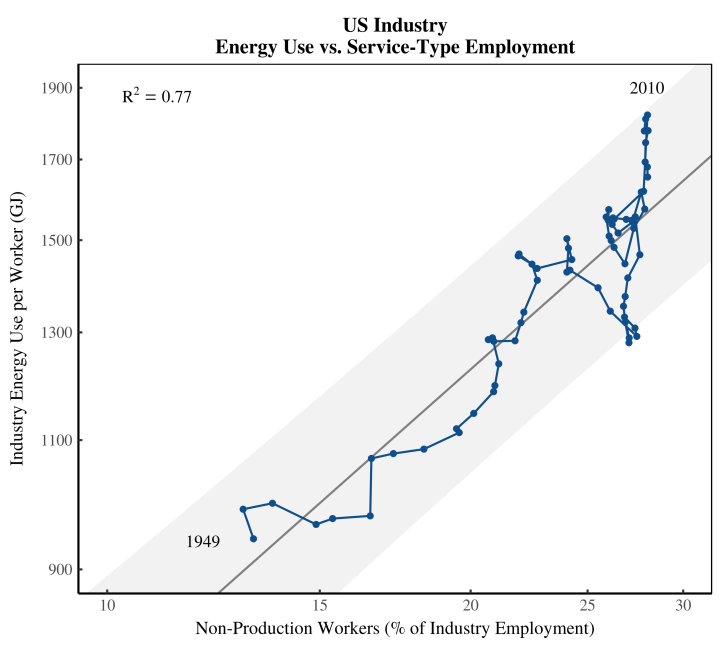

We even find the same trend within US industry. Figure 9 shows the growth of non-production workers within US industry. These workers do service-type activity, but are employed by industrial firms. As service-type activity grows, so does energy use per person.

The evidence is overwhelming. A service transition is a recipe for using more energy. So we should not be surprised that transitioning to services fails to deliver emissions relief.

Let’s have a sense of history

The idea that a service transition will increase sustainability is relative new. It dates at most to the 1970s, when rich countries began to de-industrialize. It seemed, at the time, that something new was happening. But the thing is, it wasn’t the service transition that was new.

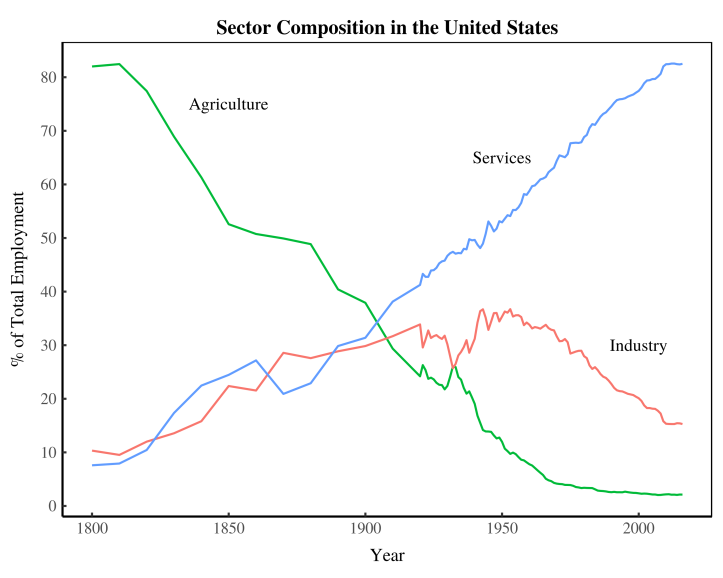

Figure 10 shows two centuries of sector change in the United States. What do you notice? I see two constant trends. Agriculture employment decreases with time, while service employment increases. These trends continue uninterrupted for two centuries. In other words, the US has been transitioning to services for over 200 years.

What changed in the 1970s? It had nothing to do with services. Instead, industrial employment collapsed. And, as many observers have noted, this industrial collapse was caused mostly by the offshoring of industrial jobs. China now does the industrial heavy lifting for much of the world.

Given that the US has been transitioning to services for 200 plus years, we need to have a sense of history. Over the last two centuries, has the United States become more sustainable? No! So let’s not delude ourselves that a service transition will lead to sustainability. It hasn’t and it won’t.

Further Reading

Dematerialization Through Services: Evaluating the Evidence. BioPhysical Economics and Resource Quality. 2019; 4(2):6. Preprint at SocArXiv.