From Lars Syll Analogue-economy models may picture Galilean thought experiments or they may describe credible worlds. In either case we have a problem in taking lessons from the model to the world. The problem is the venerable one of unrealistic assumptions, exacerbated in economics by the fact that the paucity of economic principles with serious empirical content makes it difficult to do without detailed structural assumptions. But the worry is not just that the assumptions are unrealistic; rather, they are unrealistic in just the wrong way. Nancy Cartwright One of the limitations with economics is the restricted possibility to perform experiments, forcing it to mainly rely on observational studies for knowledge of real-world economies. But still — the idea of performing laboratory

Topics:

Lars Pålsson Syll considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from Lars Syll

Analogue-economy models may picture Galilean thought experiments or they may describe credible worlds. In either case we have a problem in taking lessons from the model to the world. The problem is the venerable one of unrealistic assumptions, exacerbated in economics by the fact that the paucity of economic principles with serious empirical content makes it difficult to do without detailed structural assumptions. But the worry is not just that the assumptions are unrealistic; rather, they are unrealistic in just the wrong way.

One of the limitations with economics is the restricted possibility to perform experiments, forcing it to mainly rely on observational studies for knowledge of real-world economies.

But still — the idea of performing laboratory experiments holds a firm grip of our wish to discover (causal) relationships between economic ‘variables.’  If we only could isolate and manipulate variables in controlled environments, we would probably find ourselves in a situation where we with greater ‘rigour’ and ‘precision’ could describe, predict, or explain economic happenings in terms of ‘structural’ causes, ‘parameter’ values of relevant variables, and economic ‘laws.’

If we only could isolate and manipulate variables in controlled environments, we would probably find ourselves in a situation where we with greater ‘rigour’ and ‘precision’ could describe, predict, or explain economic happenings in terms of ‘structural’ causes, ‘parameter’ values of relevant variables, and economic ‘laws.’

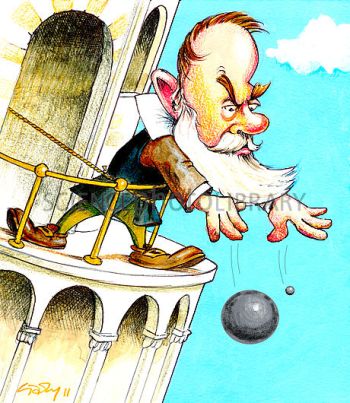

Galileo Galilei’s experiments are often held as exemplary for how to perform experiments to learn something about the real world. Galileo’s experiments were according to Nancy Cartwright (Hunting Causes and Using Them, p. 223)

designed to find out what contribution the motion due to the pull of the earth will make, with the assumption that the contribution is stable across all the different kinds of situations falling bodies will get into … He eliminated (as far as possible) all other causes of motion on the bodies in his experiment so that he could see how they move when only the earth affects them. That is the contribution that the earth’s pull makes to their motion.

Galileo’s heavy balls dropping from the tower of Pisa, confirmed that the distance an object falls is proportional to the square of time and that this law (empirical regularity) of falling bodies could be applicable outside a vacuum tube when e. g. air existence is negligible.

The big problem is to decide or find out exactly for which objects air resistance (and other potentially ‘confounding’ factors) is ‘negligible.’ In the case of heavy balls, air resistance is obviously negligible, but how about feathers or plastic bags?

One possibility is to take the all-encompassing-theory road and find out all about possible disturbing/confounding factors — not only air resistance — influencing the fall and build that into one great model delivering accurate predictions on what happens when the object that falls is not only a heavy ball but feathers and plastic bags. This usually amounts to ultimately state some kind of ceteris paribus interpretation of the ‘law.’

Another road to take would be to concentrate on the negligibility assumption and to specify the domain of applicability to be only heavy compact bodies. The price you have to pay for this is that (1) ‘negligibility’ may be hard to establish in open real-world systems, (2) the generalisation you can make from ‘sample’ to ‘population’ is heavily restricted, and (3) you actually have to use some ‘shoe leather’ and empirically try to find out how large is the ‘reach’ of the ‘law.’

In mainstream economics, one has usually settled for the ‘theoretical’ road (and in case you think the present ‘natural experiments’ hype has changed anything, remember that to mimic real experiments, exceedingly stringent special conditions have to obtain).

In the end, it all boils down to one question — are there any Galilean ‘heavy balls’ to be found in economics, so that we can indisputably establish the existence of economic laws operating in real-world economies?

As far as I can see there some heavy balls out there, but not even one single real economic law.

Economic factors/variables are more like feathers than heavy balls — non-negligible factors (like air resistance and chaotic turbulence) are hard to rule out as having no influence on the object studied.

Galilean experiments are hard to carry out in economics, and the theoretical ‘analogue’ models economists construct and in which they perform their ‘thought-experiments’ build on assumptions that are far away from the kind of idealized conditions under which Galileo performed his experiments. The ‘nomological machines’ that Galileo and other scientists have been able to construct have no real analogues in economics. The stability, autonomy, modularity, and interventional invariance, that we may find between entities in nature, simply are not there in real-world economies. That’s are real-world fact, and contrary to the beliefs of most mainstream economists, they won’t go away simply by applying deductive-axiomatic economic theory with tons of more or less unsubstantiated assumptions.

By this, I do not mean to say that we have to discard all (causal) theories/laws building on modularity, stability, invariance, etc. But we have to acknowledge the fact that outside the systems that possibly fulfil these requirements/assumptions, they are of little substantial value. Running paper and pen experiments on artificial ‘analogue’ model economies is a sure way of ‘establishing’ (causal) economic laws or solving intricate econometric problems of autonomy, identification, invariance and structural stability — in the model world. But they are pure substitutes for the real thing and they don’t have much bearing on what goes on in real-world open social systems. Setting up convenient circumstances for conducting Galilean experiments may tell us a lot about what happens under those kinds of circumstances. But — few, if any, real-world social systems are ‘convenient.’ So most of those systems, theories and models, are irrelevant for letting us know what we really want to know.

To solve, understand, or explain real-world problems you actually have to know something about them — logic, pure mathematics, data simulations or deductive axiomatics don’t take you very far. Most econometrics and economic theories/models are splendid logic machines. But — applying them to the real world is a totally hopeless undertaking! The assumptions one has to make in order to successfully apply these deductive-axiomatic theories/models/machines are devastatingly restrictive and mostly empirically untestable– and hence make their real-world scope ridiculously narrow. To fruitfully analyse real-world phenomena with models and theories you cannot build on patently and known to be ridiculously absurd assumptions. No matter how much you would like the world to entirely consist of heavy balls, the world is not like that. The world also has its fair share of feathers and plastic bags.

The problem articulated by Cartwright (in the quote at the top of this post) is that most of the ‘idealizations’ we find in mainstream economic models are not ‘core’ assumptions, but rather structural ‘auxiliary’ assumptions. Without those supplementary assumptions, the core assumptions deliver next to nothing of interest. So to come up with interesting conclusions you have to rely heavily on those other — ‘structural’ — assumptions.

Let me just take one example to show that as a result of this the Galilean virtue is totally lost — there is no way the results achieved within the model can be exported to other circumstances.

When Pissarides — in his ‘Loss of Skill during Unemployment and the Persistence of Unemployment Shocks’ QJE (1992) —try to explain involuntary unemployment, he do so by constructing a model using assumptions such as e. g. ”two overlapping generations of fixed size”, ”wages determined by Nash bargaining”, ”actors maximizing expected utility”,”endogenous job openings”, and ”job matching describable by a probability distribution.” The core assumption of expected utility maximizing agents doesn’t take the models anywhere, so to get some results Pissarides have to load his model with all these constraining auxiliary assumptions. Without those assumptions, the model would deliver nothing. The auxiliary assumptions matter crucially. So, what’s the problem? There is no way the results we get in that model would happen in reality! Not even extreme idealizations in the form of invoking non-existent entities such as ‘actors maximizing expected utility’ delivers. The model is not a Galilean thought-experiment. Given the set of constraining assumptions, this happens. But change only one of these assumptions and something completely different may happen.

Whenever model-based causal claims are made, experimentalists quickly find that these claims do not hold under disturbances that were not written into the model. Our own stock example is from auction design – models say that open auctions are supposed to foster better information exchange leading to more efficient allocation. Do they do that in general? Or at least under any real world conditions that we actually know about? Maybe. But we know that introducing the smallest unmodelled detail into the setup, for instance complementarities between different items for sale, unleashes a cascade of interactive effects. Careful mechanism designers do not trust models in the way they would trust genuine Galilean thought experiments. Nor should they.

The lack of ‘robustness’ with respect to variation of the model assumptions underscores that this is not the kind of knowledge we are looking for. We want to know what happens to unemployment in general in the real world, not what might possibly happen in a model given a constraining set of known to be false assumptions. This should come as no surprise. How that model with all its more or less outlandishly looking assumptions ever should be able to connect with the real world is, to say the least, somewhat unclear. The total absence of strong empirical evidence and the lack of similarity between the heavily constrained model and the real world makes it even more difficult to see how there could ever be any inductive bridging between them. As Cartwright has it, the assumptions are not only unrealistic, they are unrealistic “in just the wrong way.”

In physics, we have theories and centuries of experience and experiments that show how gravity makes bodies move. In economics, we know there is nothing equivalent. So instead mainstream economists necessarily have to load their theories and models with sets of auxiliary structural assumptions to get any results at all int their models.

So why do mainstream economists keep on pursuing this modelling project?