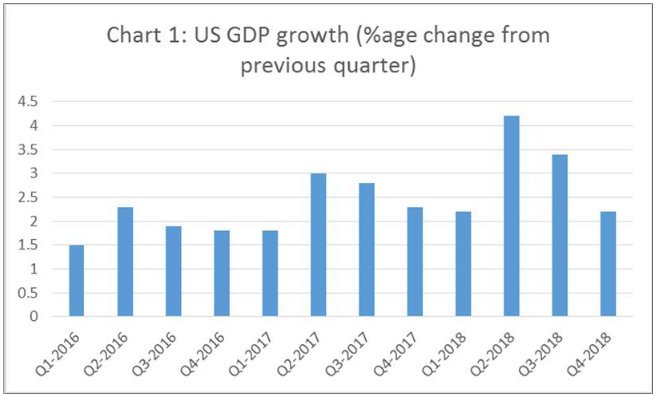

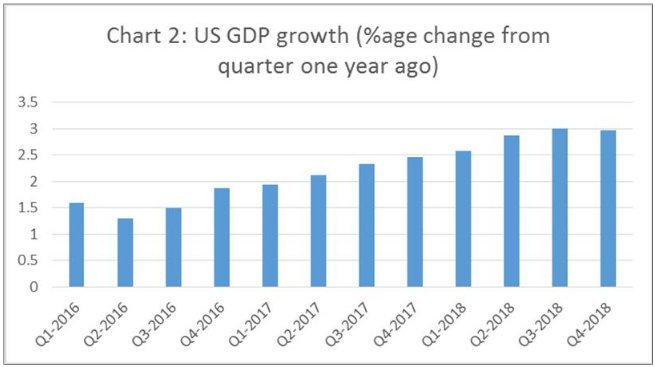

From C.P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh When the third estimate of US growth in the last quarter of 2018 was released the euphoria exuded by forecasters of global growth even a few months earlier waned. The annualised quarter on quarter growth rate that had risen to a more than comfortable 4.2 per cent in the second quarter of 2018, had fallen to 3.4 and 2.2 per cent in the subsequent two quarters (Chart 1). The quarterly rates measuring growth relative to the corresponding quarter in the previous year after having risen consistently have stagnated (Chart 2). Once again it appears that growth in the US is losing momentum, contrary to the optimistic projections of recovery that figures relating to the periods prior to the last quarter had generated. This is having repercussions at a

Topics:

Editor considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from C.P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

When the third estimate of US growth in the last quarter of 2018 was released the euphoria exuded by forecasters of global growth even a few months earlier waned. The annualised quarter on quarter growth rate that had risen to a more than comfortable 4.2 per cent in the second quarter of 2018, had fallen to 3.4 and 2.2 per cent in the subsequent two quarters (Chart 1). The quarterly rates measuring growth relative to the corresponding quarter in the previous year after having risen consistently have stagnated (Chart 2). Once again it appears that growth in the US is losing momentum, contrary to the optimistic projections of recovery that figures relating to the periods prior to the last quarter had generated.

This is having repercussions at a policy level too. The Federal Reserve, which after having tapered out its bond purchasing programme had begun raising interest rates, announced that it would not be implementing the further interest rate hikes in 2019 it had declared it was committed to.

There are a number of messages that can be read into these developments, of which four are particularly significant. The first is that the stimulus to US growth, if any, that the Trump tax-cuts and infrastructural investments had delivered, had lost its edge. The second is that the protectionist turn, focused on China, of the Trump administration was not triggering growth. The third is that though monetary policy initiatives involving infusion of liquidity and near zero interest rates had not helped deliver a recovery, that was the only option that governments seem willing to adopt. There are no signs, despite low inflation, of an effort to restore a role for fiscal policy, which could make a difference. And, the fourth is that uncertainties generated by the rise of unpredictable right-wing regimes and by the never-ending Brexit prospect have possibly had some dampening effect on investment and growth.

The despondency this has generated is also tinged with an element of alarm, because of signs of an inversion of the yield curve. While it is normal under capitalism for longer term interest rates to rule higher than short term rates, in late March, the interest rate on a three-month Treasury bill was, at 2.43 percent, 0.05 percentage points higher than the interest rate on a 10-year Treasury bond of 2.38 percent. In the past, an inverted yield curve pointing to little interest in accessing long term capital was a signal of a possible recession. Combined with the evidence on slowing growth that prospect is being referred to by many observers as a signal that another downturn is likely.

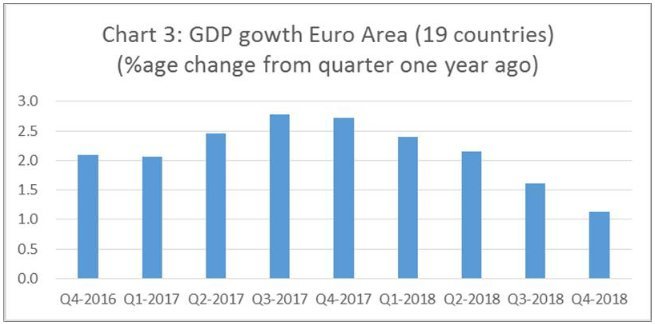

For the world economy, these developments on the US front are especially troubling, because the US was expected to pull the rest out of a recessionary quagmire. Economies in the eurozone are languishing with annualised quarterly growth rates in the 19 euro area countries falling consistently since the third quarter of 2017 (Chart 3). From a high of 2.8 per cent in that quarter, growth is down to just 1.1 per cent in the last quarter of 2018. The long-term buoyancy displayed by Germany has given way to projections that the country’s growth in 2019 would be lower than 1 per cent as compared with earlier expectations of nearly 2 per cent. As compared with a peak rate of 2.8 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2017, Germany’s GDP rose by just 0.6 per cent year-on-year in the fourth quarter of 2018.

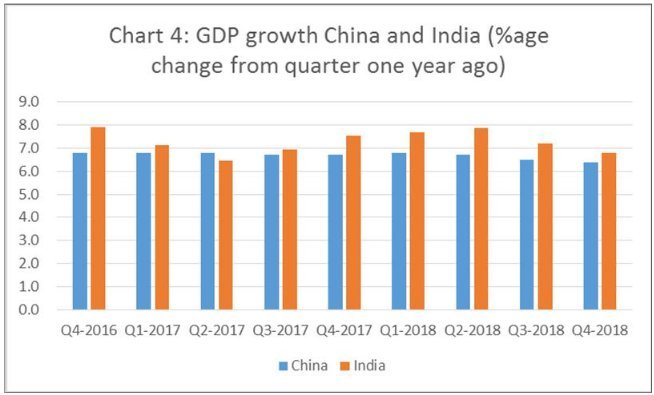

Elsewhere, the two fast growing emerging markets, China and India are also showing signs of losing momentum (Chart 4). After having been stuck with year-on-year growth rates of 6.7-6.8 per cent for seven quarters ending Q2 2018, GDP growth in China has moved further down to 6.4 per cent by Q4 2018. India’s quarterly rates have been volatile, but have come down from 7.9 per cent to 6.8 per cent in the three quarters ending Q4 2018. These were the economics that were seen as decoupled from the rest of the world system at the time of the 2008 crisis, and capable of lifting the rest out of recession. They too seem to be slipping now.

To any sensible observer, ten years of waiting for a robust recovery should have driven home one lesson. Since everything tried so far has not worked, the only option left is a strong countercyclical thrust delivered by restoring a leading role for fiscal policy. But there are two among many other factors constraining the exercise of that option. The first is the power of finance, restored after the financial crisis through state action in the form of fiscal support to prevent insolvency and monetary support with cheap and bountiful credit to help financial firms ride back to profit. But having won back strength and power finance stands as a bulwark against any effort to use fiscal policy that would legitimise the state and delegitimise the market.

The second is that in a globalised world with absent capital controls and hence volatile cross-border financial flows, no one nation can choose to adopt a proactive fiscal policy by itself. Since government deficits are anathema for finance, that could trigger capital outflows and a precipitous depreciation of the currency. What is needed is a coordinated fiscal stimulus. Unfortunately, the cooperative spirit among nations needed for action of that kind is absent, and was seen in recent times only briefly during the worst phase pf the 2008 crisis and the Great Recession that followed.

In sum, the world is poised in a peculiar situation. Slow growth can possibly give way to recession. Monetary policy has been pushed to its limits without much success. And even the little effect it had in recent times cannot be realised if there is another recession, since there is little monetary headroom available. Yet the mainstream consensus is that proactive fiscal policies, whose role circumstances demand must be restored, must be abjured. One crisis has not been enough for the system to restructure itself, so that another is now a real possibility.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on April 8, 2019)