From Blair Fix A revolution is underway around us and it’s called the digital. And it’s changing everything. More than 80% of wealth is now non-material. — Charles Foran in Just don’t say his name: the modern left on Karl Marx’s place in politics (41:30) Both critics and cheerleaders of capitalism claim it has. The critics see non-material wealth as a problem. Digital wealth, they say, is fictitious. It’s lost touch with reality. The cheerleaders of capitalism see the same thing as a boon. Non-material wealth, they say, will decouple the economy from physical constraints. So the economy can grow forever! Which side is right? Neither, in my opinion. Instead, both sides misunderstand the nature of wealth. Wealth is not becoming non-material. No. Wealth has always been non-material. So

Topics:

Editor considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from Blair Fix

A revolution is underway around us and it’s called the digital. And it’s changing everything. More than 80% of wealth is now non-material.

— Charles Foran in Just don’t say his name: the modern left on Karl Marx’s place in politics (41:30)

Both critics and cheerleaders of capitalism claim it has. The critics see non-material wealth as a problem. Digital wealth, they say, is fictitious. It’s lost touch with reality.

The cheerleaders of capitalism see the same thing as a boon. Non-material wealth, they say, will decouple the economy from physical constraints. So the economy can grow forever!

Which side is right?

Neither, in my opinion.

Instead, both sides misunderstand the nature of wealth. Wealth is not becoming non-material. No. Wealth has always been non-material. So the digital revolution isn’t changing the nature of wealth. It’s just laying bare the facts that have always been there.

What is wealth?

We use the word ‘wealth’ all the time. We say things like “Bill Gates is wealthy”, or “The United States is a wealthy nation”. But what do we mean by this? What exactly is ‘wealth’?

When we stop to think about the word ‘wealth’, we find that it has two meanings.

Sometimes we use the word ‘wealth’ to mean stuff — a stock of goods. So wealthy people are those who have lots of stuff. They own mansions, sports cars, yachts and private jets. Think of the opulence showcased on the 1980s show Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous.

But wealth can also mean money. If I have a billion dollars in the bank, I’m wealthy — even if I have no stuff at all.

So is wealth stuff? Or is it money?

Mainstream economists say it’s both. Wealth, they say, has two sides. It’s both a ‘real’ stock of goods and a symbolic stock of money. The key, economists say, is that the two sides are related. The monetary side of wealth quantifies the material side. Conversely, the material side of wealth is what ‘backs’ the monetary side.

Wealth distortions

Because (say economists) wealth has two sides, this opens the door for ‘distortions’. A distortion occurs when the two sides of the wealth coin don’t add up. Somehow monetary wealth gets out of whack with material wealth.

When monetary wealth overstates material wealth, economists say there’s a bubble. Conversely, when monetary wealth understates material wealth, economists say that assets are ‘undervalued’. In either case, monetary value isn’t doing its job correctly. It’s distorting (rather than representing) the ‘true’ stock of material wealth.

The idea of a wealth distortion is used by people of all political stripes. Curiously, their claims are often mutually contradictory.

Mainstream economists use the idea of wealth distortions to advocate free markets. Government intervention, they claim, ‘distorts’ prices. If the government would just let the market be, wealth distortions would go away and ‘true’ prices would be restored. At least, that’s what economists tell us.

Critics of capitalism turn this logic on its head. They see wealth distortions as a sign that capitalism (not government) has run amok. Companies like Facebook and Google, critics observe, are worth billions of dollars. But these companies don’t produce anything ‘real’. And so the critics claim that wealth is becoming fictitious. And this, in turn, is a sign that capitalism is in trouble. It’s lost touch with material reality.

In contrast, techno-optimists think digital wealth is good for capitalism. It’s a sign that companies are learning to produce (real) wealth without using resources. So we should celebrate, because wealth is becoming decoupled from material constraints.

Nearly everybody, it seems, uses the idea of wealth distortions to promote their (mutually contradictory) agendas. This is a sure sign that there’s a problem with our concept of wealth. Ideas that are infinitely malleable usually turn out to be wrong. Or worse, they’re not even wrong (they can never be tested).

The duality of wealth probably falls into both categories.

It’s not even wrong because there is no single way to objectively measure the material side of wealth. Any material definition of wealth is based on subjective decisions about the dimension of analysis. And these decisions affect the resulting stock of ‘real’ wealth. (See The Aggregation Problem for an explanation of this dilemma). So the idea that monetary value could misrepresent the stock of ‘real’ wealth is untestable.

The duality of wealth is also just plain wrong. It’s based on a misunderstanding of the nature of wealth. Wealth is not about property — the stuff that is owned. Instead, wealth is about the act of ownership. Wealth is about property rights.

Property vs. property rights

What’s the difference between property and property rights? Think of the difference between a fence and whatever it surrounds. The fence represents property rights. The stuff inside the fence is property.

This distinction is important, because the value of wealth doesn’t stem from property. It stems from property rights. Without the fence of property rights, anyone can use your property for free. And when it’s free, your property has no value. So monetary wealth depends on property rights, not property itself.

Skeptical? Think about this real-life example. A hotshot programmer creates a new operating system. The OS is heralded as revolutionary and is adopted by millions of people.

Does the programmer become wealthy?

It depends on property rights.

Suppose our programmer is Bill Gates. When he released MS-DOS (and later Windows), Gates fiercely enforced property rights. He patented his software and made people pay to use it. Through a series of shrewd deals with manufacturers, Microsoft eventually gained a near monopoly on PC operating systems. And as we all know, Gates became a wealthy man.

Now suppose our programmer is Linus Torvalds. In the 1990s, Torvalds created the Linux operating system. Although adoption was slow at first, Linux now dominates the server market. And through its derivative, Android, Linux also dominates the smartphone market.

So Torvalds got rich, right? Actually no. Torvalds released Linux as open source software, meaning it’s free for anyone to use. Because Torvalds didn’t enforce property rights, he didn’t get rich like Bill Gates.

The lesson here is that without property rights, goods and services don’t have a price. And without a price, they don’t get counted as ‘wealth’.

Don’t look inside the fence

Property rights are the fence that gives property value. Now here’s the important thing. When it comes to determining value, it doesn’t matter what’s inside the fence. It could be a house. It could be machinery. It could be knowledge. What matters is the fence itself. The fence — the ability to enforce property rights — is the source of the owner’s monetary wealth.

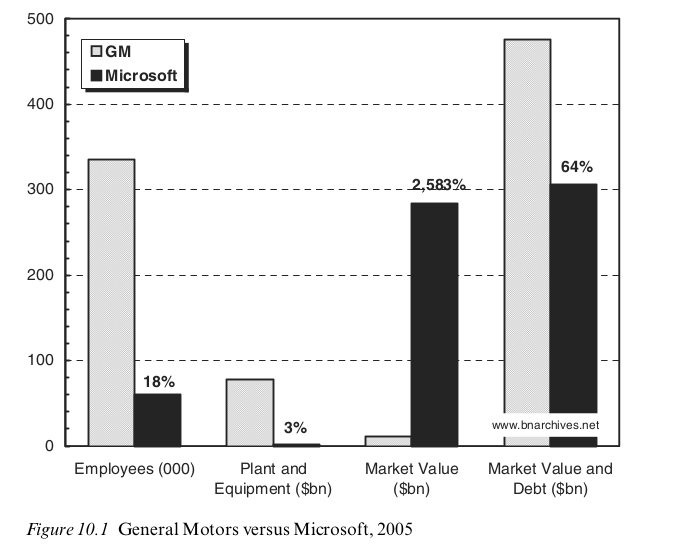

To illustrate that it doesn’t matter what’s inside the fence of property rights, Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler compare Microsoft and General Motors. The chart below shows different features of each company.

In 2005, Microsoft’s market value was 2,583% greater than that of General Motors. Mainstream economists would say that Microsoft therefore had more property than GM. But more of what? Nitzan and Bichler point out that when we look under the hood of market value, there’s nothing ‘real’ to back it up. Microsoft, for instance, has only 18% as many employees as GM. And it owns only 3% as much equipment (in dollar terms).

So is this a distortion? Is it a sign that Microsoft’s wealth is fictitious? No, say Nitzan and Bichler. Wealth isn’t about material property. Instead, they argue that wealth is a commodification of property rights. So Microsoft’s greater market value stems from its greater ability to convert property rights into income. That Microsoft can do this without owning bricks and mortar is interesting, but not surprising. As intellectual property teaches us, property rights need not be attached to anything physical.

The power of owners

If monetary wealth stems from property rights, how should we interpret its value? Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshom Bichler have a provocative answer. The value of property rights, they argue, indicates the relative power of owners.

Nitzan and Bichler’s reasoning is simple. Property rights are about exclusion. And exclusion is about power:

The most important feature of private ownership is not that it enables those who own, but that it disables those who do not. Technically, anyone can get into someone else’s car and drive away, or give an order to sell all of Warren Buffet’s shares in Berkshire Hathaway. The sole purpose of private ownership is to prevent us from doing so. In this sense, private ownership is wholly and only an institution of exclusion, and institutional exclusion is a matter of organized power. (Nitzan and Bichler in Capital as Power)

If we think like Nitzan and Bichler, we realize that wealth is not a thing. It’s an act. Wealth is the commodification of an act of exclusion — an act we call property rights.

When only the fence is left

If Nitzan and Bichler are right (and I think they are), then the digital revolution is not making wealth non-material. Instead, it’s just laying bare the fact that wealth has always been non-material. Wealth has always been about power.

What has confused economists for centuries is that they’ve focused on what’s inside the fence of property rights, not the fence itself. And who can blame them? Historically, the things that were owned were easy to see. In contrast, the act of ownership — the institutional fence of private property — was abstract. And so economists tied wealth to property, not the property-rights fence.

The confusion dates back to the physiocrats. They saw agricultural land and proposed that it was the source of all value. The physiocrats couldn’t see that it was the landowner’s (institutional) fence that made him wealthy, not the land itself.

Then came the neoclassical economists. They saw capital (machines and factories) and proposed that it was a source of value. The neoclassical economists couldn’t see that it was the capitalist’s (institutional) fence that made him wealthy, not capital itself.

Then came the digital revolution. New companies emerged (like Facebook and Google) that owned nothing but algorithms. Wealth had suddenly become non-material. Or so it seemed to economists.

In reality, wealth had always been non-material — a social relation of exclusion. The digital revolution just laid this fact bare because it emptied out property, leaving only the fence of property rights. The digital revolution got rid of land. It got rid of physical capital. It got rid of all the physical things on which to pin wealth. All that was left (in digital tech firms) was the fence of property rights. And this fence was put up around the most non-material of things — ideas themselves.

Changing power

If the digital revolution isn’t making wealth non-material, what is it doing?

Like previous revolutions, the digital revolution is changing who has power in our society. Tech firms are wrestling power from industrial firms. Two hundred years ago the industrial revolution did something similar. In it, the captains of industry wrestled power from the landed aristocracy.

Nitzan and Bichler’s insight is to realize that we can study the power of different types of owners using the value of their property rights. This is an exciting research area that we’re only beginning to investigate.

So yes, the value of property rights is increasingly dominated by tech firms. But no, this doesn’t mean that wealth is becoming non-material. Wealth is the commodification of a social relation — the right of owners to exclude everyone else. As such, wealth has always been non-material.