From Dean Baker We know that the economy is likely to get worse in the immediate future as the pandemic is spreading out of control in most parts of the country. However, the latest data on average weekly hours indicates we may be facing a longer-term issue that has not generally been anticipated. In a normal recession, we see both a loss of jobs and a reduction in hours for those who managed to keep their jobs. The shortening of hours is a better way for employers to deal with reduced demand for labor since it keeps workers attached to their jobs. (This is the argument for work-sharing as an alternative to unemployment.) However, in this recession, we are actually seeing some lengthening of the average workweek, not the usual shortening. The chart below compares the change in the

Topics:

Dean Baker considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from Dean Baker

We know that the economy is likely to get worse in the immediate future as the pandemic is spreading out of control in most parts of the country. However, the latest data on average weekly hours indicates we may be facing a longer-term issue that has not generally been anticipated.

In a normal recession, we see both a loss of jobs and a reduction in hours for those who managed to keep their jobs. The shortening of hours is a better way for employers to deal with reduced demand for labor since it keeps workers attached to their jobs. (This is the argument for work-sharing as an alternative to unemployment.) However, in this recession, we are actually seeing some lengthening of the average workweek, not the usual shortening.

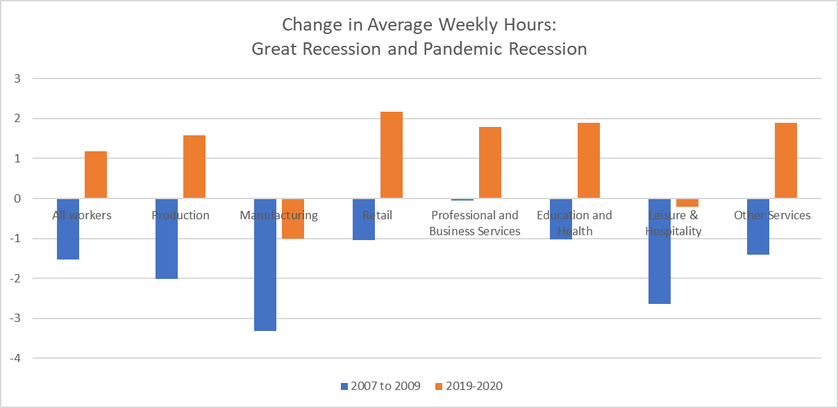

The chart below compares the change in the average workweek from 2007 to 2009 and from 2019 to 2020. For 2020, I have used the most recent two months’ data (September and October) to just take the period where the economy was operating at a level somewhat close to normal.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics and author’s calculations.

As can be seen, we see a very different picture in the pattern of work hours between the two recessions. The average workweek for all employees fell by 1.5 percent in the Great Recession. By contrast, it increased by 1.2 percent from 2019 to September and October of this year. Some of this was undoubtedly due to composition effects. In the Great Recession, like most recessions, construction and manufacturing were the hardest hit sectors. These sectors have longer average hours than most, so job loss in these sectors will automatically reduce the length of the average workweek.

To control for this, I have compared the change in average hours in the two recessions for production and non-supervisory workers in several major sectors. Starting with the overall average, the difference is even sharper. The drop in the Great Recession was 2.0 percent, compared to a 1.6 percent increase in the Pandemic Recession.

Looking at major sectors, there was a drop in the length of the average workweek of 3.0 percent in manufacturing in the Great Recession compared to 1.0 percent in this recession. This may be explained largely by the fact that manufacturing was much harder hit in the Great Recession.

This explanation doesn’t fit for other sectors. Average hours fell by 1.1 percent in retail in the Great Recession, they rose by 2.2 percent in this recession. In the broad category of professional and business services, hours fell by 0.1 percent in the Great Recession, they have risen by 1.8 percent in this recession.

In education and health care, average hours fell by 1.0 percent in the Great Recession, they have risen by 1.9 percent in this recession. In the category leisure and hospitality, which includes hotels and restaurant workers, hours fell by 2.7 percent in the last recession, compared to a drop of just 0.2 percent in this recession. Hours in other services, which includes areas like laundry, gyms, and hair salons, fell by 1.4 percent in the Great Recession, they have risen by 1.9 percent in this recession.

The rise in hours during this recession is a really big deal because it accentuates the unemployment problem. To take the simple arithmetic, if the average workweek is 3 percent longer because of a change in employer behavior, with our pre-pandemic employment of roughly 150 million, that means 4.5 million fewer jobs given the same demand for labor. The real world will of course always be more complicated, but the basic story would apply. Longer hours means fewer jobs.

This is likely to matter not just for the immediate future when the pandemic limits employment in large areas of the economy, but also in the longer term, as we adjust to the work structures that have been permanently altered as a result of the recession. As I have written elsewhere, the increase in telecommuting is likely to be enduring, meaning that there will be many fewer jobs serving a smaller population of commuters.

One way of dealing with this reduction in employment opportunities is to have shorter work weeks/work years. Unfortunately, it seems we are now headed in the wrong direction.