From David Ruccio It must be confessed that though the plague was chiefly among the poor, yet were the poor the most venturous and fearless of it, and went about their employment with a sort of brutal courage; I must call it so, for it was founded neither on religion nor prudence; scarce did they use any caution, but ran into any business which they could get employment in, though it was the most hazardous. Such was that of tending the sick, watching houses shut up, carrying infected persons to the pest-house, and, which was still worse, carrying the dead away to their graves. — Daniel Defoe, A Journal of the Plague Year I’m almost sick of hearing the refrain, “We’re all in this together.” I say almost, because I do think there’s a utopian moment in that phrase in the midst of the

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

It must be confessed that though the plague was chiefly among the poor, yet were the poor the most venturous and fearless of it, and went about their employment with a sort of brutal courage; I must call it so, for it was founded neither on religion nor prudence; scarce did they use any caution, but ran into any business which they could get employment in, though it was the most hazardous. Such was that of tending the sick, watching houses shut up, carrying infected persons to the pest-house, and, which was still worse, carrying the dead away to their graves.

— Daniel Defoe, A Journal of the Plague Year

I’m almost sick of hearing the refrain, “We’re all in this together.”

I say almost, because I do think there’s a utopian moment in that phrase in the midst of the current pandemic. It speaks of solidarity, of being in common, of paying attention to and honoring healthcare workers and others who are currently laboring in “essential” activities while the rest of us are instructed to stay at home. In that sense, it betokens—or at least aspires to—a thinking about and caring for others.

Otherwise, and this is why I’m getting tired of it, the expression serves to deflect our attention from and to paper over the obscene inequalities that afflict American society. I’m referring not only to the pre-existing unequal condition in the United States—the sharp fissures and enormous chasms that have been highlighted by the pandemic—but also to the ways the gap between the haves and have-nots has played an important role in actually causing the spread of the dreaded disease, as well as to the possibility those inequalities will only get worse as a result of the pandemic and the way the response to it has been devised and implemented in the United States.

It has now become almost commonplace, at least within the liberal mainstream media, to note that the unfolding of the novel coronavirus pandemic and the ensuing economic crisis have focused a spotlight on the grotesque inequalities that preceded their onset. With every day that has gone by, it has become clearer that the spread of the virus has been profoundly lopsided and uneven—from access to testing and decent, affordable healthcare and who’s been able to shelter in place to the presence of underlying “comorbidities,” all of which have made the virus both more prevalent and more lethal among working-class Americans, including African Americans, who have been left behind.

The pandemic has also brought with it an economic crisis—and that too has reflected existing inequalities. On one hand, tens of millions of low-wage workers have been especially vulnerable to layoffs, with restaurant and retail workers especially at risk, increasingly obliged to acquire sustenance for themselves and their families in the country’s understocked food pantries. On the other hand, millions of other workers—who drive buses, care for hospital patients and the elderly, pack and transport commodities, take their places on the assembly-line in slaughterhouses—have been forced to have the freedom to continue to commute to and labor at their jobs in perilous conditions, increasing the risk of contagion to themselves, their families, and the communities in which they live.

Meanwhile, the former or current employers of those same workers have been lining up to receive loans from private banks and through the various government bailouts, with few of any restrictions (e.g., on stock buybacks and dividends payments to shareholders) and high-profile chief executives of corporations have announced voluntary salary cuts, which turn out to be nothing more than publicity stunts.

Not only do the consequences of the pandemic appear to reflect existing inequalities. It also seems to be the case that those same inequalities are acting as multipliers on the coronavirus’s spread and deadliness. It is no coincidence that the United States, with the most unequal distribution of income and wealth among rich countries, also has the highest number of confirmed cases of and deaths from the coronavirus. One reason is that, as inequality has increased, health disparities themselves have widened—and lower-income Americans are much likelier than those at the top to have one or more chronic health conditions, thus exposing them to more risk from the coronavirus. Moreover, those same people are the ones who have been continuing to work in their “essential” in-person jobs, which require more contact both with other workers and customers. In other words, workers, who have more health problems and less health care, are at greater risk of transmission.

The pandemic under extreme inequality thus involves a devastating feedback loop, for workers and society as a whole. The people who can least afford it, given their health and working conditions, are forced into the position of being more exposed to contagion and becoming agents of transmitting the disease to others—in their workplaces and households and in the wider community.

And there’s another feedback loop, or cycle of injustice—from existing inequalities through the uneven effects of the pandemic to even more inequality in the future. As Charlie Cooper has argued,

With social distancing here to stay for the foreseeable future, it’s becoming increasingly clear that the next stage of the pandemic is going to change many lives for the worse.

Specifically, it’s going to exacerbate existing inequalities, as the privileged buffer themselves against its pernicious effects while the world’s most vulnerable struggle not to fall through the rapidly widening economic fissures.

For one thing, even after recovery from the immediate affliction, the coronavirus infection may cause lasting damage throughout the body, thereby worsening both the health and economic activity of some (still unknown) portion of an entire generation.

On top of that, the effects of the economic crisis, with tens of millions of workers furloughed or laid off while banks and corporations are bailed out and the stock market is on the rebound, may be even worse than those of the Second Great Depression. Let’s remember that, aside from a brief hiatus (in 2009), the trend of growing inequality that preceded the crash of 2007-08 was quickly restored during and after the so-called recovery.

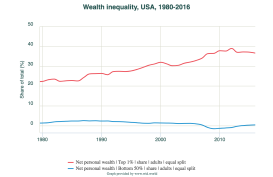

For example, in 2007, the top 1 percent of Americans captured 19.9 percent of pretax national income (the blue line in the chart on the left), while the bottom 50 percent had only 13.7 percent (the red line). By 2014 (the last year for which data are available), the percentages were 20.2 and 12.6, respectively. The story of wealth inequality is even more dramatic: while the share of wealth owned by the top 1 percent (the red line in the chart on the right) grew from 34.1 percent in 2007 to 36.6 percent in 2016, the tiny share owned by the bottom 50 percent (the blue line) barely changed, rising from 0.3 percent to 0.4 percent.

Since we’re only at the beginning of the current crisis, we still don’t know what the final results will be. Even a quick, V-shaped economic recovery (about which I have my doubts) would still be accompanied, according to current modeling, with millions of cases of coronavirus and 100 thousand or more deaths, spread unevenly within the U.S. population (especially now that the Trump administration is set to dismantle its coronavirus task force). While the effects of a longer and more severe downturn—a third economic depression, perhaps—will likely be characterized, especially since there have been no major policy changes compared a decade ago, by the same kind of unequalizing dynamic.

All signs, then, point to the fact that existing inequalities will give rise, on their own and through the consequences of the pandemic, to even more obscene levels of inequality in the future—unless, of course, there is a profound change in the way the American economy and healthcare system are currently organized.

Undoing those inequalities is the only way of ensuring that, in reality, “we’re all in this together.”