David Ruccio If we needed any more confirmation of who’s been laid off during the current crisis, all we need to do is examine the change in average hourly wages in the United States. In the past month (so, April 2020), the year-over-year increase in hourly wages jumped to 7.9 percent. That’s more than three times the average increase since 2008 (2.5 percent) and more than two and half times the increase since Donald Trump took office (3 percent). That doesn’t mean American workers are now earning more. Oh, sure, perhaps a few, who have been granted temporary increases to commute and work in precarious conditions—the ones who were receiving so-called “heroic pay,” which in many cases (such as Kroger supermarkets) is now being cancelled. No, the April increase mostly tells us, first,

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

David Ruccio

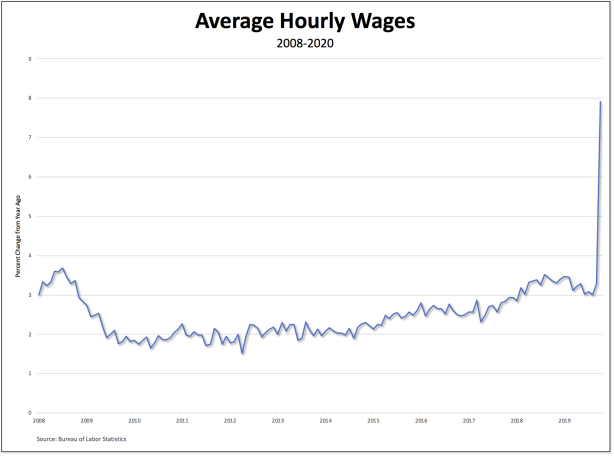

If we needed any more confirmation of who’s been laid off during the current crisis, all we need to do is examine the change in average hourly wages in the United States.

In the past month (so, April 2020), the year-over-year increase in hourly wages jumped to 7.9 percent. That’s more than three times the average increase since 2008 (2.5 percent) and more than two and half times the increase since Donald Trump took office (3 percent).

That doesn’t mean American workers are now earning more. Oh, sure, perhaps a few, who have been granted temporary increases to commute and work in precarious conditions—the ones who were receiving so-called “heroic pay,” which in many cases (such as Kroger supermarkets) is now being cancelled. No, the April increase mostly tells us, first, that tens of millions of works have been laid off and, second, that the vast majority of the workers who were fired in April were at the lower end of the wage scale.

Those low-wage workers—in retail, hospitality, healthcare, and other sectors—are no longer employed. So, their wages don’t count as part of the average. Therefore, the average hourly wage (of all private-sector workers), in comparison to last year at the same time, rose dramatically.

What it means, then, is those who can least afford it, have been let go and are now struggling to survive on unemployment insurance and charity from food banks. They are the new members of the reserve army of unemployed workers, which in the months and years ahead will serve to hold down wage increases for and generally weaken the position of all workers.

That, alas, is how capitalist labor markets are working (for employers) and not working (for employees) during this pandemic crisis.