From David Ruccio I’ve often read that people who wash their hands in innocence do so in blood-stained basins. And their hands bear the traces.— Bertolt Brecht, Mother Courage The first time care for elderly and chronically ill Americans was radically transformed was during the first Great Depression, as almshouses were overwhelmed and public support grew to replace old-style charitable “indoor relief” with new-style government-funded “outdoor relief,” based on cash payments to people to support themselves in the community. According to Sidney D. Watson (pdf), “The Social Security Act of 1935 embodied this new approach to American social welfare, creating cash benefit programs to provide the elderly and needy with the money to support themselves at home rather than in institutions.”*

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

I’ve often read that people who wash their hands in innocence do so in blood-stained basins. And their hands bear the traces.

— Bertolt Brecht, Mother Courage

The first time care for elderly and chronically ill Americans was radically transformed was during the first Great Depression, as almshouses were overwhelmed and public support grew to replace old-style charitable “indoor relief” with new-style government-funded “outdoor relief,” based on cash payments to people to support themselves in the community. According to Sidney D. Watson (pdf), “The Social Security Act of 1935 embodied this new approach to American social welfare, creating cash benefit programs to provide the elderly and needy with the money to support themselves at home rather than in institutions.”*

The first time care for elderly and chronically ill Americans was radically transformed was during the first Great Depression, as almshouses were overwhelmed and public support grew to replace old-style charitable “indoor relief” with new-style government-funded “outdoor relief,” based on cash payments to people to support themselves in the community. According to Sidney D. Watson (pdf), “The Social Security Act of 1935 embodied this new approach to American social welfare, creating cash benefit programs to provide the elderly and needy with the money to support themselves at home rather than in institutions.”*

Later, the Social Security Amendments of 1950, 1956, 1960, and 1965 (which created Medicaid), a combination of federal and state payments fueled the growth of nursing homes by expanding eligibility and authorizing states to make vendor payments directly to for-profit care institutions. The existing nursing home industry fought to get Medicaid funding and, through its lobbying efforts, to keep and expand based on Medicaid funding.** It then used those funds to warehouse the elderly and infirm, in the care of workers who earn low wages, most of whom are women of color, a large portion of whom are immigrant workers.

Now, those same nursing homes, like the almshouses of the 1930s, have been overwhelmed by a “tidal wave of human need”—but for a very different reason: they have become one of the key sites of the novel coronavirus pandemic.

According to a recent investigation by the New York Times, about one-third of all U.S. coronavirus deaths are nursing-home residents or workers. At least 25,600 residents and workers have died from the coronavirus at nursing homes and other long-term care facilities for older adults in the United States, which has infected more than 143,000 people at some 7,500 facilities. Moreover, in about a dozen states, the number of residents and workers who have died accounts for more than half of all deaths from the virus.***

For example, in Massachusetts, more than half the state’s deaths, 2,922, come from long-term care facilities that have become major sources of infection. As of this past Saturday, 336 long-term care centers in the state had reported at least one COVID-19 case and some 15,965 residents and health care workers have been sickened.

Unfortunately, the existing data can’t for the most part distinguish between patients and workers. What we do know is that most nursing-home patients (60 percent) are supported by Medicaid, and therefore are (or are made) poor or near-poor. Across the country, they are being infected by and dying from COVID-19 at rates that are much higher than for the general population.

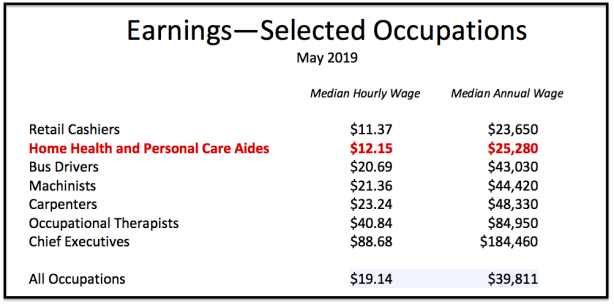

As for the more than 3 million nursing-home workers in the United States, they earn a median wage of $12.15 an hour, for a median annual wage of only $25,280.**** The chart above demonstrates that, while the typical nursing-home worker earns more than retail cashiers, their wages and annual pay put them substantially below the national average as well as many other occupations, from bus drivers to chief executives.

We also know that, thanks to a recent study (pdf) by PHI (formerly the Paraprofessional Healthcare Institute), a great deal about the demographic makeup of the nursing-home workforce (which, for their purposes, include, in addition to home health and personal care aides, nursing assistants). It is predominantly (86 percent) female, a majority (59 percent) people of color (including 30 percent who are Black and 18 percent Latinx), and about one in four (26 percent) born outside the United States. Because of their low wages, about 1 in 7 nursing-home workers live in poverty, almost half (44 percent) are low-income (defined as below twice the poverty line), and 2 in 5 (42 percent) require some form of public assistance.

Taken together, these data reveal a workforce that is collectively marginalized in the labor market.

Unfortunately, it should come as no surprise, given the obscene levels of inequality in the United States and the nature of long-term care for the elderly and infirm, that both residents and workers in nursing homes occupy a marginalized position in American society. As a result, both groups are living and working—and, increasingly, dying—in one of the veritable hellholes of the current pandemic.

For a century now, the United States has not had to rely on charity and poorhouses to care for the elderly and infirm. But if we didn’t know before, then surely the effects of the novel coronavirus pandemic have demonstrated how much their replacement—the nursing-home industry—like many other capitalist institutions, has failed to protect both those who have been placed in its care and those who have worked so diligently, under impossible conditions, to provide that care. Today, the nursing-home industry requires a transformation that is as at least radical as the one that was started during the first Great Depression.

In the meantime, the industry needs to be pushed by individual states and the federal government, by any means necessary, to rescue its residents and workers from their pandemic-induced nightmare.

*Watson argues that

The Social Security Act was an epochal event in American social welfare. It reflected a belief that public assistance recipients should, and could, be trusted to spend their benefits as they saw fit and that use of “in-kind” benefits was unnecessary, demeaning, and stigmatizing. The disabled would continue to be cared for through “indoor relief” in a variety of institutions including mental asylums, tuberculosis sanitariums, public hospitals, and schools for the deaf.

**As Watson explains,

By making nursing home care free for all senior citizens without assets, nearly half of the elderly in 1975, Medicaid provided a powerful incentive to families to institutionalize parents, who might previously have moved in with grown children or sought the part-time care of a home health aide. By offering states a federally funded alternative to state psychiatric hospitals, nursing homes also became the place to institutionalize those with developmental disabilities and long-term mental illness.

***The BBC recently reported that one-third of all coronavirus deaths in England and Wales are now happening in “care homes”—an ominous feature of the Anglo-American response to the pandemic.

****Bureau of Labor Statistics earnings data are for 3,161,500 Home Health and Personal Care Aides (2018 SOC occupations 31-1121 Home Health Aides and 31-1122 Personal Care Aides and the 2010 SOC occupations 31-1011 Home Health Aides and 39-9021 Personal Care Aides) for May 2019.