From David Ruccio How many of you read Car and Driver magazine? Not many of you, I presume. But maybe you should. At least the June 2020 issue. It’s certainly a sign of our obscenely unequal times that a magazine better known for its reviews of foreign supercars and domestic muscle cars and for an editorial policy that courts controversy only when it attacks SUVs (in favor of minivans and cars) highlights the story of Oliver, Jason M. Vaughn’s family’s 260,000-mile Subaru in a piece subtitled “The Fear of Failure.” Turning the key has become an act of faith. As the engine grumbles to life on this fine southwest Colorado morning, the yellow check-engine light comes on, as it has every day for the past four years, and the same questions swirl in my mind. Is this the day that tiny

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

How many of you read Car and Driver magazine?

Not many of you, I presume. But maybe you should. At least the June 2020 issue.

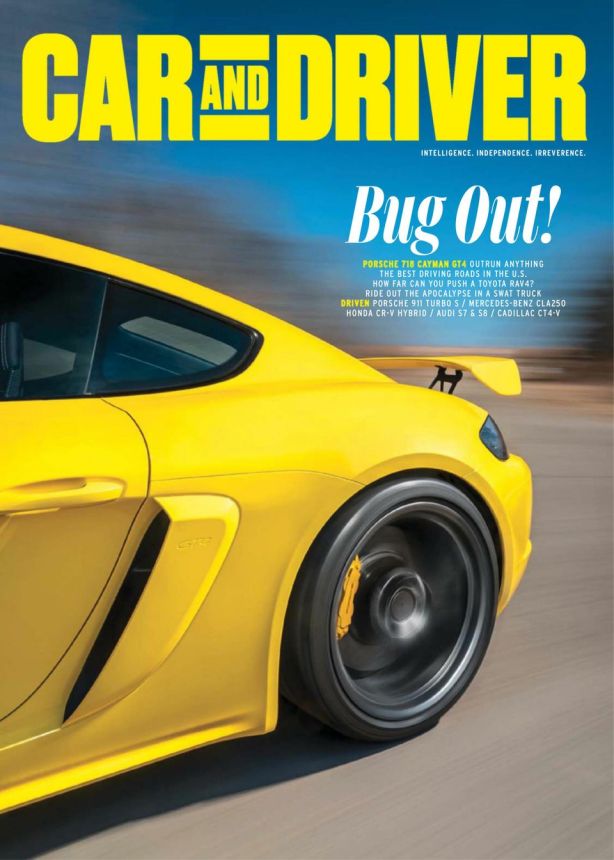

It’s certainly a sign of our obscenely unequal times that a magazine better known for its reviews of foreign supercars and domestic muscle cars and for an editorial policy that courts controversy only when it attacks SUVs (in favor of minivans and cars) highlights the story of Oliver, Jason M. Vaughn’s family’s 260,000-mile Subaru in a piece subtitled “The Fear of Failure.”

Turning the key has become an act of faith. As the engine grumbles to life on this fine southwest Colorado morning, the yellow check-engine light comes on, as it has every day for the past four years, and the same questions swirl in my mind. Is this the day that tiny head-gasket leak turns into a gusher? Is this the day the catalytic converter chokes closed for good? Is this the day that one speck of sand too many works its way into that cracked CV-joint boot, causing it to seize up at some bend in the road and send me spinning into a ravine, not to be discovered until spring?. . .

I intimately know everything wrong with this car. I feel the squishy brakes and the engine straining to get up a hill, and I hear the ominous grinding sounds coming from under the right-front wheel well. But I can’t afford to do anything to ward off those looming disasters.

That’s because Vaughn’s family is like many American households, who don’t have any emergency savings and therefore can’t cover a surprise $400 expense without borrowing money or selling something. Or they can’t come up with the money at all.

Oliver, purchased new in 2004, is also like many other cars on U.S. roads, in being old (at 11.8 years old, the average age of the 278 million vehicles on American highways has never been higher). One reason is because

many Americans—in a time of stagnant wages combined with soaring consumer debt and a high cost of living—can’t afford to replace their old beaters. Or if they can get another vehicle, they’re only able to replace it with another beater.

As for Vaughn, he and his wife were both laid off from their respective, “and not very lucrative jobs,” last year and they can’t afford to keep up on the current maintenance, much less fix all the stuff on the car they’ve been putting off.

That’s why Vaughn identifies so much with Linda Tirado, the author of the 2014 book, Hand to Mouth: Living in Bootstrap America, an account of what it’s like, day after day, to work, eat, shop, raise kids, and keep a roof over your head without enough money. One of the lessons Vaughn highlights is the predicament of the poor working-class:

One of the hardest ironies of all for the working poor is the often unspoken truth that in America, you usually have to already have money to even get an opportunity to make money. And simply moving someplace with better jobs and higher pay isn’t really an option when you’re broke.

To keep Oliver running, Vaughn has taught himself some basic maintenance and repairs (via YouTube videos, of course) and resorted to cheap fixes that betray “more than a twinge of desperation”—all in the hope that the Subaru can last another 100,000 miles. The fact is,

We’ll probably need another 100,000 miles out of Oliver whether we can properly care for him or not.

That makes a lot of sense. It’s exactly the predicament more and more working-class drivers and their cars find themselves in as economic inequality, already grotesque, continues to soar in the United States.

Clearly the problem of inequality is so serious and so widespread that it has forced its way into a Hearst-owned automotive enthusiast magazine, squeezed between articles on the new Porsche 718 Cayman GT4 (price as tested: $118,600) and a golden-wheeled, Kar Tunz-modified Lamborghini Urus (price: $277,904).

Now, tell me, is there a better illustration of what life is like in the United States in the age of inequality?