From David Ruccio In the United States and around the world, governments are responding to the twin pandemics—of novel coronavirus and escalating unemployment—with massive bailouts. Not unlike what happened more than a decade ago, after the global crash of 2007-08. But there seems to be something different this time around—not only because of the speed of both the viral contamination and the economic meltdown, but also as a reaction to the terms of the bailout that was enacted in the midst of the Second Great Depression. Here, for example, is Peter S. Goodman reflecting on the response in Britain and the European Union: During the last crisis, the global financial catastrophe of 2008, the authorities protected corporate interests above those of ordinary people, many economists assert.

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

In the United States and around the world, governments are responding to the twin pandemics—of novel coronavirus and escalating unemployment—with massive bailouts. Not unlike what happened more than a decade ago, after the global crash of 2007-08.

But there seems to be something different this time around—not only because of the speed of both the viral contamination and the economic meltdown, but also as a reaction to the terms of the bailout that was enacted in the midst of the Second Great Depression.

Here, for example, is

During the last crisis, the global financial catastrophe of 2008, the authorities protected corporate interests above those of ordinary people, many economists assert. Britain and the European Union bailed out financial institutions, then recovered the costs by hacking away at public services, effectively punishing laborers and taxpayers for the sins of wealthy bankers.

Just like that, with no apparent controversy, he drops in the idea that, after the last major crash, those in charge sought to safeguard corporations and neglect the interests of “ordinary people.” That was certainly the stance, in the United States, of groups like the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street but Goodman now asserts it as a commonly held view, with a gesture to authority (“many economists assert”).

Another example is NBC News Senior Business correspondent Stephanie Ruhle, certainly no radical, who argues the last bailout “didn’t trickle down to workers,” and strings need to be attached to corporations in any new bailout.

Even Donald Trump said he would be “OK” with a conditional coronavirus bailout that bans stock buybacks for companies that receive federal relief—joining both Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren.

The question is, is something going on here—in the United States, Europe, and perhaps elsewhere—that represents a shifting of the ground, a fundamental change in the common sense concerning economic issues?

Now, to be clear, I am using the term common sense not in the manner of Thomas Paine or as it is often invoked in English, but instead as it figured prominently in the writings of the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci, in his Prison Notebooks. As Kate Crehan explains in the preface to her insightful and prescient book, Gramsci’s Common Sense: Inequality and Its Narratives (Duke University Press),

the Italian senso comune is a far more neutral term than the English common sense. The English term, with its overwhelmingly positive connotations, puts the emphasis, so to speak, on the “sense,” senso comune on the held-in-common (comune) nature of the beliefs. In the notebooks, Gramsci reflects on the complicated roots of such collective knowledge, its shifting and often contradictory components, the ways it becomes accepted as beyond question—and by whom—and when, and how it changes. The collective here is important: “What matters is not the opinion of Tom, Dick, and Harry but the ensemble of opinions that have become collective and a powerful factor in society.”

Common sense, as I am deploying it here, is a generally accepted, collective, body of knowledge, a way of understanding or interpreting what is going on in the world that appears, at least at any moment in time, as beyond dispute. Moreover, there is nothing fixed about common sense, since it can—indeed, we should expect it to—shift and change over time.*

So, again, the question is, has the common sense about economic issues been moving in a new direction in recent weeks?

It’s pretty clear, at least to those of us on the Left, that the $2.2 trillion (or, if you count the leveraging, close to $6 trillion) CARES Act is mostly a bailout to large corporations—Boeing, the airline industry, and, with little oversight, any other corporation that manages to get its snout into the trough.

In fact, as Tim Wu and

The companies that will be receiving the largest bailouts were, until recently, enjoying unprecedented levels of corporate profitability, thanks to large corporate tax cuts, industry mergers and the avoidance of significant wage increases for employees.

And, indeed, spending enormous sums on stock buybacks, which reward only shareholders and increase executive pay.

But the way the bailout has been discussed, at least outside the halls of Congress and the White House, reflects a critique of the bailout of Wall Street and the automobile industry that was orchestrated by the administrations of George W. Bush and Barack Obama after the crash of 2007-08. The ground, it seems, has shifted.

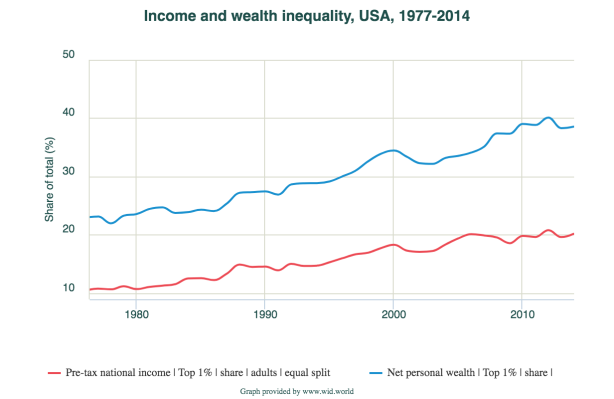

The debate about the terms of the bailout—across media platforms, from many different pundits and political perspectives—has been much more attuned to how workers and others got completely shafted in the previous “recovery” and how corporations, banks, and the rich were handed bags of money, almost none of which “trickled down” to workers, poor people, and others at the bottom of the economic pyramid. Even more, the way the bailout was structured added to the ability of those at the top to capture the lion’s share of whatever new income and wealth were generated in the aftermath. My sense is, there is a common understanding that economic inequality in the United States got a whole lot worse because of the way the bailout was first envisioned and then enacted.

Even the Wall Street Journal now admits, joining others in acknowledging the new common sense:

what many remember from a decade ago is that after the banks were bailed out, the stock market and financial industry rebounded, while ordinary workers and homeowners struggled with stagnant wages and underwater mortgages.

But, of course, this shift hasn’t occurred in a vacuum. In addition to concerns about how the United States was transformed in a much more unequal manner during the Second Great Depression, people have witnessed how inadequate the U.S. private, profit-driven, medical-industrial complex has been in either preparing for or responding to the health pandemic.** And workers—those toiling away on the front lines of overburdened and perilous public health facilities, the many who are required to abandon their families and endure unsafe conditions while laboring in “essential” industries, and the millions and millions of others who are being forced to join the reserve army of the unemployed and underemployed—are the ones who are paying the costs.

To be clear, the outcome of this changing common sense is still quite uncertain. If it has shifted, and I think it has, it has taken on dimensions that both the nationalist right and the progressive left have been able to seize on. Private markets have failed, grotesque levels of inequality are driving the divergent costs of the health and unemployment pandemics, and the previous bailout enriched a small group at the top and failed, more than a decade on, to reach the vast majority of American workers. But that common understanding of what has gone wrong in recent years opens up new possibilities for both ends of the political spectrum when it comes to economic issues.

Where this changing common sense actually ends up will depend on who is more effective in pushing and pulling that collective understanding. As I see it, the final result depends on the work of intellectuals as well as the lived experience of the “masses,” the reporting on events in the media and the positions articulated by political parties, comparisons with what is happening in other countries and what can be delivered in newly imagined ways of organizing economic and social life.

There will be many, of course, who, in the midst of the current crises, will call for the previous common sense to be restored.*** My view, for what it’s worth, is that time is past. The old common sense has been effectively discarded. We just don’t know, at this point, which one will take its place.

*The other, related term that has some play in the United States is the so-called Overton Window, which was produced within public choice economics and is central to the work of the conservative think tank the Mackinac Center for Public Policy. What I don’t particularly like about the Overton Window is that it is defined not as a body of collective knowledge, which comprises “shifting and often contradictory components,” but instead as a set of policy options, a “window,” that forms the boundaries of political debate.

**The irony, of course, is, the ideas and policies that Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren articulated during the campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination, which the extreme moderates in the party did their best to stamp out, have become increasingly “mainstream,” especially in reaction to the crash that has happened and will no doubt escalate in the midst of the health and unemployment pandemics.

***The tragic irony is that Joe Biden, the presumptive Democratic nominee, is precisely the candidate who has articulated and defended the Obama administration’s bailout and thus the old common sense. How exactly he’s going to invoke the previous common sense and position himself and his party to defeat Trump in the November election is anybody’s guess.