From David Ruccio The coronavirus outbreak is serving as a mind-expansion exercise, making hitherto unthinkable solutions thinkable. Debts that can’t be paid won’t be. A debt jubilee may be the best way out. — Michael Hudson The United States is currently experiencing a dystopian orgy of death and destruction. In the midst of the novel coronavirus pandemic, hundreds of thousands of Americans are falling ill, tens of thousands are dying, and everyone else is living in fear they’ll contract the dreaded disease. Meanwhile, tens of millions of workers have either been laid off from their jobs, losing both their paychecks and healthcare benefits, or are being forced to have the freedom to work under precarious and unsafe conditions. Not surprisingly, they want some relief—both

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

The coronavirus outbreak is serving as a mind-expansion exercise, making hitherto unthinkable solutions thinkable. Debts that can’t be paid won’t be. A debt jubilee may be the best way out.

The United States is currently experiencing a dystopian orgy of death and destruction.

In the midst of the novel coronavirus pandemic, hundreds of thousands of Americans are falling ill, tens of thousands are dying, and everyone else is living in fear they’ll contract the dreaded disease. Meanwhile, tens of millions of workers have either been laid off from their jobs, losing both their paychecks and healthcare benefits, or are being forced to have the freedom to work under precarious and unsafe conditions.

Not surprisingly, they want some relief—both short-term assistance, to pay their bills, and long-term reassurance that a plan is being assembled that will enhance and enrich their lives and those of their family members, communities, and country. Not just getting back to the old normal but a plan to move them to a new and improved normal.

While they wait in vain for that relief, American workers watch as the corporate behemoths they work for are being bailed out, to the tune of $2 trillion (and much more than that, when we take into account the additional trillions the Federal Reserve is pushing into the banking system). Their $1200 stimulus checks and expanded unemployment benefits simply pale in comparison.

So, why not give them some real relief?

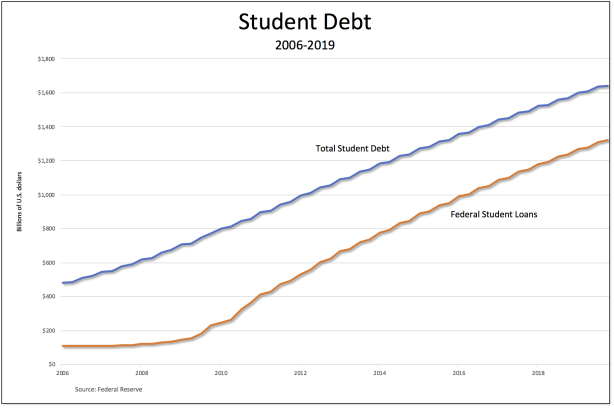

My suggestion is a student debt jubilee. The United States should forgive—simply wipe off the books—the $1.3 trillion in loans students and their families owe to the government.

Yes, I understand, I didn’t invent the idea. Bernie Sanders proposed cancelling student debt during the campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination, and most of the other candidates adopted some version of the plan. I thought it was a good idea then, and it turns out to be an even better idea now.

Cancelling the federal portion of the student loans would wipe off the books 80 percent of the total student debt in the United States. That would be a tremendous relief, in principal and interest payments, to current and former students and their families.

Moreover, it would make up for the inadequate online courses many of them are finishing up with right now (notwithstanding the heroic efforts of their professors), and make it easier to imagine continuing or enrolling in college—whatever form that takes—this coming fall. And it would help all those former students who are either working for paltry paychecks or trying to get by on less-than-generous unemployment benefits. They wouldn’t have to worry about repaying their student loans.

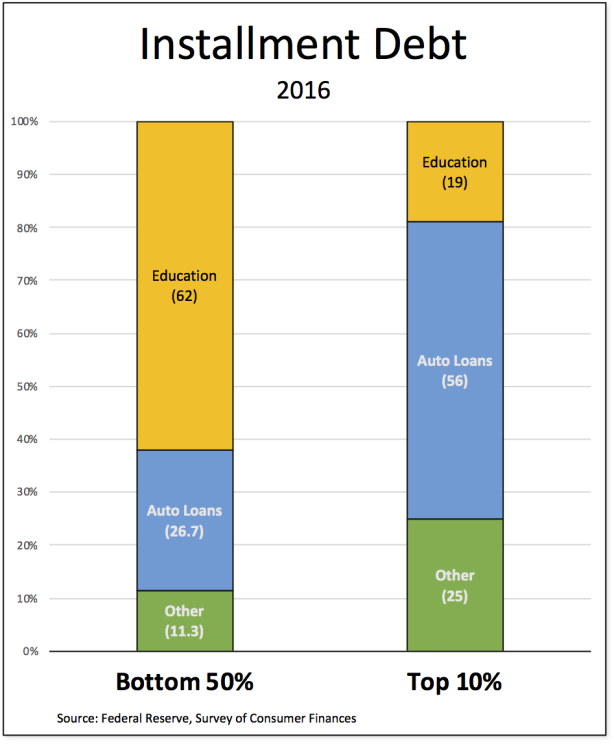

And for those who are concerned about means-testing such a jubilee, consider the fact that, as I showed last fall, for Americans in the bottom 50 percent of the distribution of income, the largest portion—almost two-thirds—of their total installment debt goes to finance their own or their children’s education.*

Now, can it happen? Sure. First, the total debt students have with the U.S. government could be forgiven with a single piece of legislation. (Forgiving the rest of the debt, the 20 percent owed to private lenders, would be a bit more complicated. It would probably require the government’s purchasing that debt, to the tune of $322 billion, and even that shouldn’t be too difficult given the scale of the current bailouts.)

Second, there are precedents. The one that occurs immediately, which came up during the Greek debt crisis, was the 1953 London Debt Accord, which resulted in the cancellation of half of Germany’s (then West Germany’s) debt: 15 billion out of a total of 30 billion Deutschmarks. As Gregori Galofré-Vilà et al. explain,

Even if we were to ascribe the most cynical and instrumental motivations to the LDA of 1953 (namely, the need for a strong Germany in the context of the Cold War of the 1950s, in addition to the realization of the errors of the Versailles Peace Conference and their subsequent effects), it is clear that this debt relief was emphatically designed to help Germany grow and always prioritized German economic health over the repayment of the debt. This involved significant sacrifices by creditors (in the form of renouncing a significant part of their debt), but also the implementation of mechanisms to avoid any risk of stagnating the German economy by the burden of debt repayments.

And it was a success. A decade later, Germany had no debt problems.

A student debt jubilee for American students and workers would have similar effects, affording them substantial breathing room to get through the current crisis and look forward, once a plan is in place, to leave their homes, rejoin their family and friends, and resume their activities.

*According to the latest Survey of Current Finances by the Federal Reserve, 31 percent of Americans in the bottom half carry student loans, and their average outstanding education debt is $34 thousand. (For those in the bottom 25 percent, it’s even worse: 40 percent of families have student debt, and their average is $43 thousand.) Just student debt is considerably more than the $23,250 average annual pre-tax income of those in the bottom 50 percent.