From David Ruccio The phrase, which was used in the early nineteenth century to describe the the spoils system of appointing government workers, accurately describes the American economy today.* And it’s pretty clear who the victor is, and it’s not the working-class. Instead, a small group at the top have come out as the victor—and that’s been true for decades now. How do we know? Well, all we have to do is look at the growing gap between the amount produced by American workers and what they received in their wages. Gross Domestic Product (the green line in the chart above) grew by a factor of almost 16 from 1973 onward while workers’ wages increased by a bit more than 5 before the COVID Depression. So, American workers only received back in the form of wages a small percentage

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

The phrase, which was used in the early nineteenth century to describe the the spoils system of appointing government workers, accurately describes the American economy today.* And it’s pretty clear who the victor is, and it’s not the working-class.

Instead, a small group at the top have come out as the victor—and that’s been true for decades now.

How do we know?

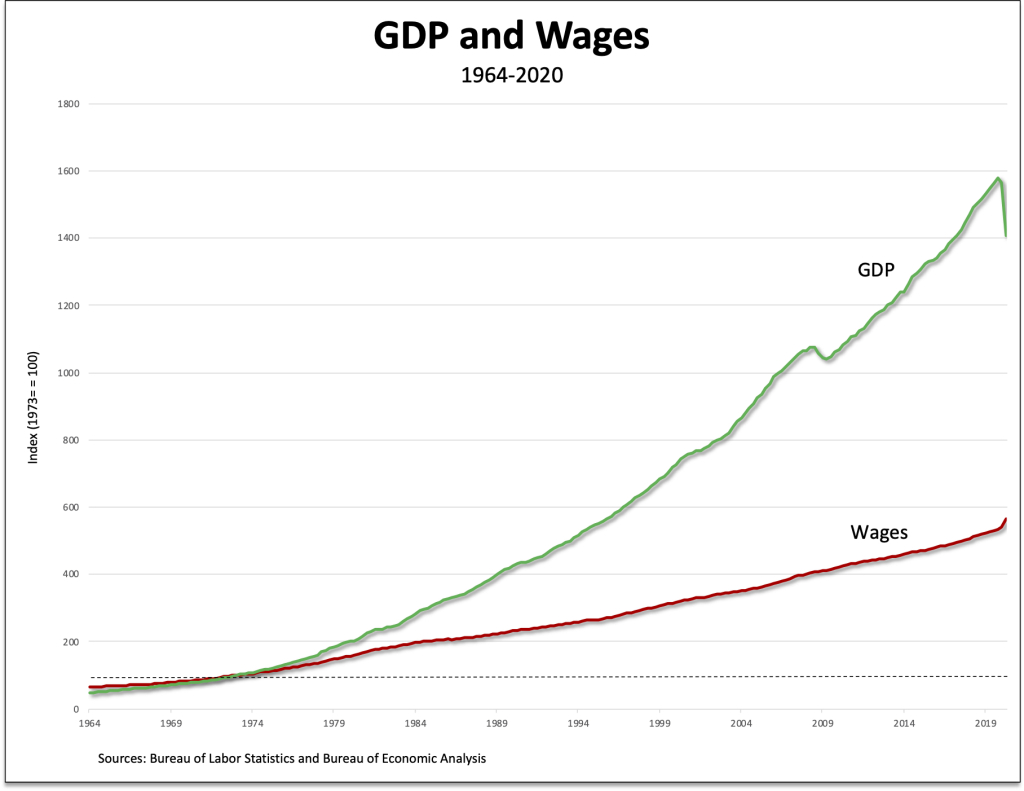

Well, all we have to do is look at the growing gap between the amount produced by American workers and what they received in their wages. Gross Domestic Product (the green line in the chart above) grew by a factor of almost 16 from 1973 onward while workers’ wages increased by a bit more than 5 before the COVID Depression.

So, American workers only received back in the form of wages a small percentage of the increased amount they produced. The rest went to their employers.

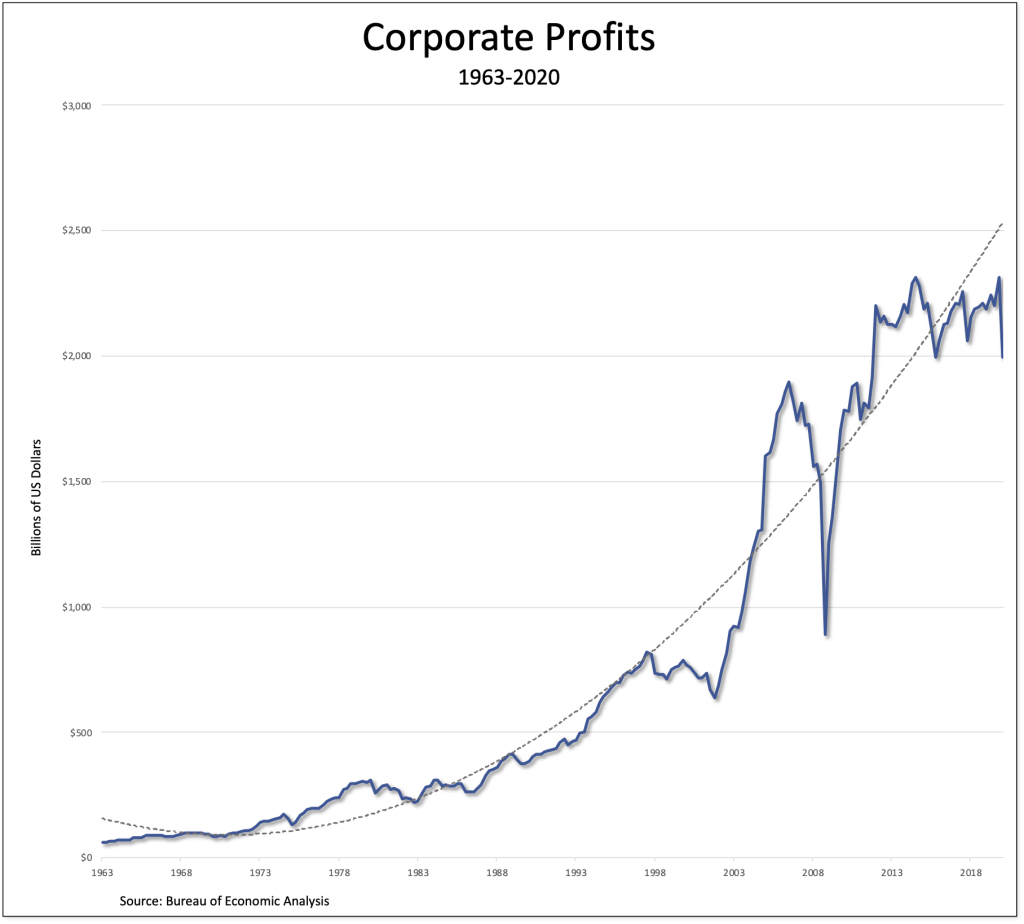

The result has been an enormous rise in U.S. corporate profits (before tax, without inventory valuation and capital consumption adjustments)—particularly evident in the trendline fitted to the data in the chart above.

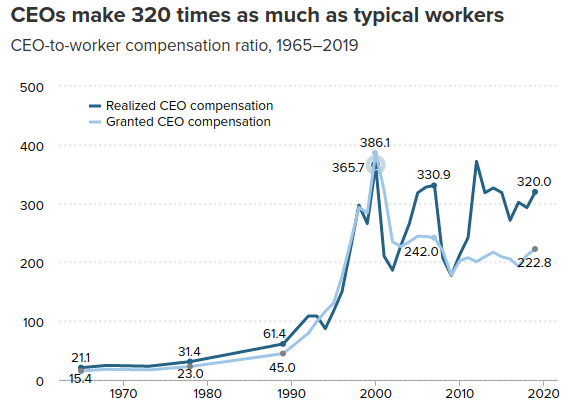

The employers, in turn, transferred a portion of those profits to the Chief Executive Officers of their corporations.

According to the latest report from the Economic Policy Institute, in 2019, a CEO at one of the top 350 firms in the United States was paid $21.3 million on average (using a “realized” measure of CEO pay that counts stock awards when vested and stock options when cashed in rather than when granted). The ratio of CEO-to-typical-worker compensation was therefore 320-to-1 (222.8-to-1 using a different, “granted” measure of CEO pay). That is up from 293-to-1 in 2018 and a gigantic increase from 61.4-to-1 in 1989 and, even more, 21.1-to-1 in 1965.

Exorbitant CEO pay is a major contributor to rising inequality that we could safely do away with. CEOs are getting more because of their power to set pay—and because so much of their pay (about three-fourths) is stock-related, not because they are increasing productivity or possess specific, high-demand skills. This escalation of CEO compensation, and of executive compensation more generally, has fueled the growth of top 1.0% and top 0.1% incomes, leaving less of the fruits of economic growth for ordinary workers and widening the gap between very high earners and the bottom 90%. The economy would suffer no harm if CEOs were paid less (or were taxed more).

An even large—and growing—distribution of the surplus that is the basis of corporate profits has taken the form of dividends, paid to owners of corporate equities. In 1965, dividends were about 26 (25.8) percent of corporate profits; by the beginning of this year they were almost 70 (69.2) percent.

And according to my calculations, the top 1 percent in the United States owns (as of 2014, the last year for which data are available) 62 percent of corporate equities, which has been climbing since the late 1970s. Meanwhile, the share of the entire bottom 90 percent has been falling, and is now only 11 percent.

So, it’s really only the small group at the top that is in a position to “share in the booty” by receiving a cut of corporate profits in the form of CEO pay and stock dividends. They’ve occupied the position of victor for decades now, and to them belong the economic spoils.**

Everyone else is forced to have the freedom to try to get by on their slowly rising wages—and to watch with both fascination and horror the ongoing spectacles in corporate boardrooms and the stock market.

——————

*”To the victor belong the spoils” is attributed to Senator William Learned Marcy of New York who, in 1832, defended Andrew Jackson, whose campaign against President John Quincy Adams was seen partly as a vendetta against Adams, and whose conduct and remarks when taking office seemed to justify the association of Jackson with the spoils system.

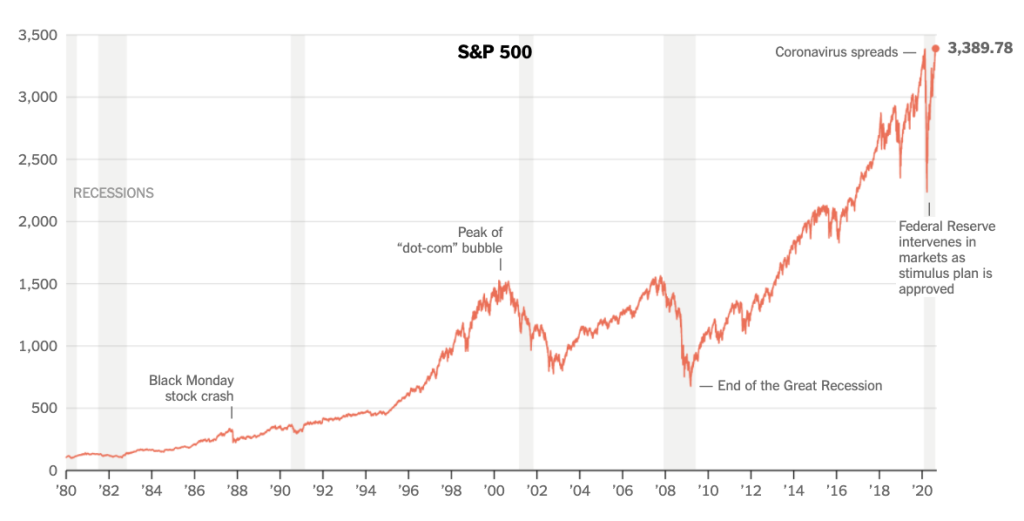

**Just yesterday, in the midst of the pandemic and the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression of the 1930s, the U.S. stock market reached a new high (according to the Standard & Poor’s 500 index).