From Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan This note contextualizes the ongoing U.S. policy shift toward greater ‘regulation’ of large corporations. Cory Doctorow (2021) and Blair Fix (2021) are optimistic about this shift. We doubt it. The Limits of Power Large U.S.-based corporations are extremely powerful, but the growth of their power has decelerated considerably. Figure 1, updated from our ‘Corporate Power and the Future of U.S. Capitalism’ (Bichler and Nitzan 2021), shows the earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) of the top 200 U.S.-based corporations, ranked by market capitalization, relative to those earned by the average U.S. corporation. The top series confirms that this differential – which proxies the relative power of the top 200 firms – has grown exponentially,

Topics:

Editor considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan

This note contextualizes the ongoing U.S. policy shift toward greater ‘regulation’ of large corporations. Cory Doctorow (2021) and Blair Fix (2021) are optimistic about this shift. We doubt it.

- The Limits of Power

Large U.S.-based corporations are extremely powerful, but the growth of their power has decelerated considerably.

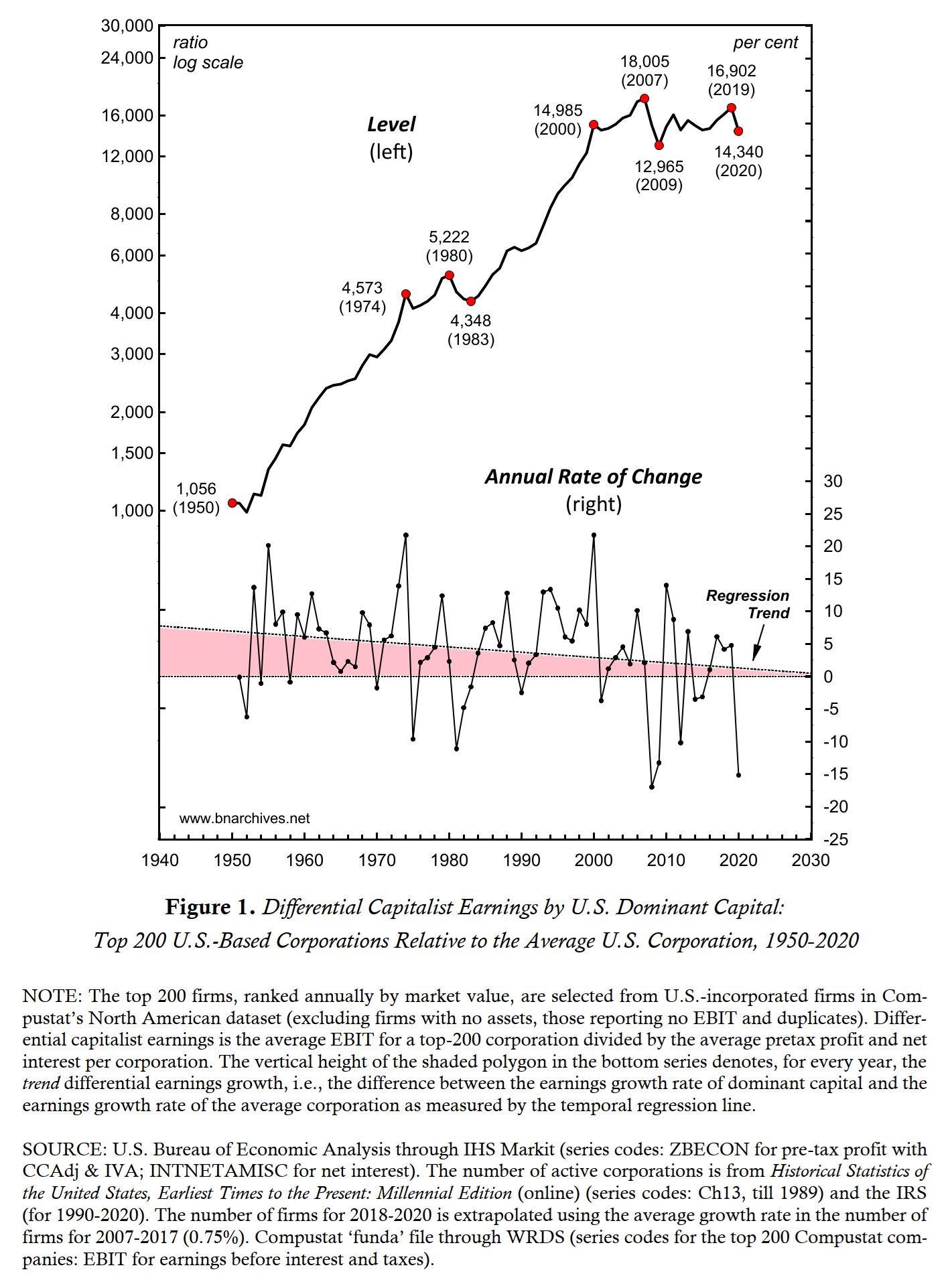

Figure 1, updated from our ‘Corporate Power and the Future of U.S. Capitalism’ (Bichler and Nitzan 2021), shows the earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) of the top 200 U.S.-based corporations, ranked by market capitalization, relative to those earned by the average U.S. corporation. The top series confirms that this differential – which proxies the relative power of the top 200 firms – has grown exponentially, rising from roughly 1,000 in 1950 to more than 15,000 in the 2000s. The bottom series, though, shows that the rate at which this differential power has grown trends downwards.

This long-term deceleration is not accidental. In fact, it is built into the very nature of social power. In our capital-as-power research – or CasP, for short – we argue that power always elicits resistance from those on whom it is imposed; that this resistance tends to rise along with power; and that the greater the resistance the more difficult it is to augment power even further. In other words, power is self-limiting (Bichler and Nitzan 2012, 2016, 2020).

The twenty-first century revival of anti-corporate sentiments and anti-capitalist movements around the world is part of this resistance – as are some of the policy reforms emerging in their wake. But these reforms shouldn’t be over-hyped.

- The Capitalist Mode of Power

Our CasP analysis claims that, as capitalism develops, governments and large corporations become increasingly intertwined organs of the same capitalist mode of power. We call this mode of power the ‘state of capital,’ and we label the large government-backed corporate coalitions at its core ‘dominant capital’.

The coalescence of governments into the capitalist mode of power does not mean that ‘policymakers’ can no longer take an independent stance. They can. But the likelihood of them doing so, as well as the scope of their independence, tend to diminish as the capitalist mode of power creorders – or creates the order of – more and more aspects of social and private life. As this corporate-government integration unfolds, government organizations and officials, including ‘reformers’, not only get entangled in the web of capitalized power, but they also find themselves conditioned by its very concepts, symbols, ideologies and rituals. Consequently, most of them cannot even conceive of fundamental change, let alone bring it about.

From this broad perspective, a meaningful shift within capitalism – and certainly a shift away from it – is less and less likely to come from above. If this shift is to materialize – and in our view, the current prospects for it remain dim – it is likely to come not from reformist governments and soulful corporations, but from below or from without. It will be affected either by social movements mobilized by radical rethinking of capitalized power, or by environmental calamity. Finally, and importantly, this change is likely to materialize not peacefully, but conflictually.

- Why are Neoliberal Governments so Big?

Think of contemporary governments. Since the 1980s, neoliberal ideology has demanded that state ‘intervention’ and ‘regulation’ be scaled back. It has called for capitalist efficiency to substitute for bureaucratic red tape, for market transparency to replace state corruption, and for equal opportunity to displace hierarchical power. It insists that government should stop ‘crowding-out’ private investment and cease interfering with the so-called free market. It argues that for markets to expand, governments must shrink.

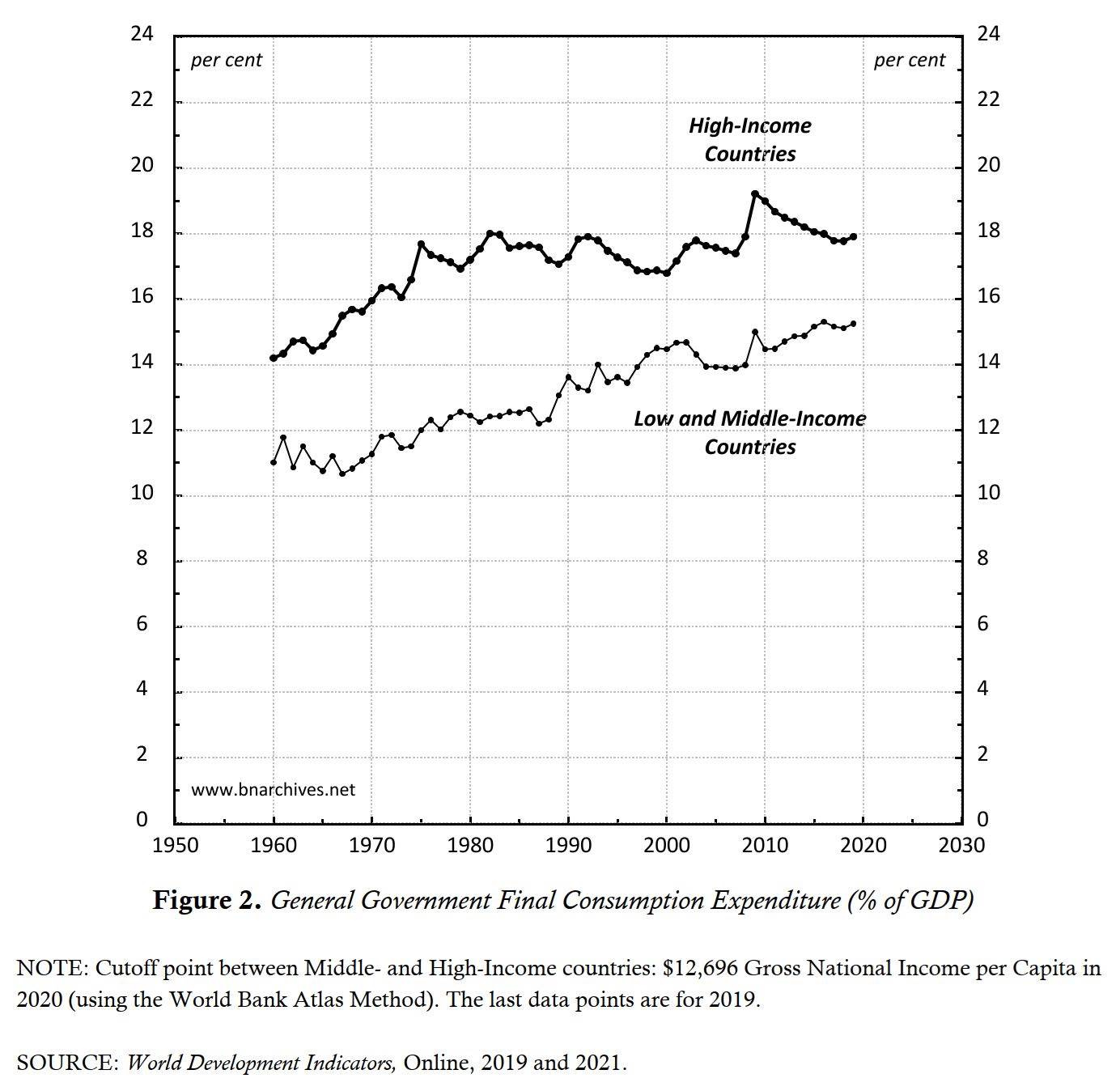

And yet, as Figure 2 shows, the victory of neoliberalism hasn’t made government any smaller. Not by a long shot. In high-income countries, the national income share of government consumption spending remains as large as it was before the onset of neoliberalism, while in low- and middle-income countries, it continues to grow bigger and bigger.

And that shouldn’t surprise us. The capitalist mode of power and the dominant-capital coalitions that rule it do not require small governments. In fact, in many respects, they need larger ones.

As a mode of power, capitalism thrives on multiple forms of ‘strategic sabotage’ – that is, on limiting and redirecting the energy of human beings toward the augmentation of capitalizing power. Dominant capital prevents most people from cooperating, democratically and directly, to improve the well-being of their society and environment. Instead, it forces them to fortify and amplify the very capitalized power that dominates them. And this forcing requires a whole slew of threats, limitations, and the open use of force – in other words, it begets strategic sabotage.

The thing is that, left unregulated, strategic sabotage can easily overbuild, causing the mode of power to implode under its own weight. And that’s where government spending comes in as a mitigating force. From this viewpoint, bigger government – particularly its sprawling social programs and transfer payments – mirrors not the failure of neoliberalism, but its very success.

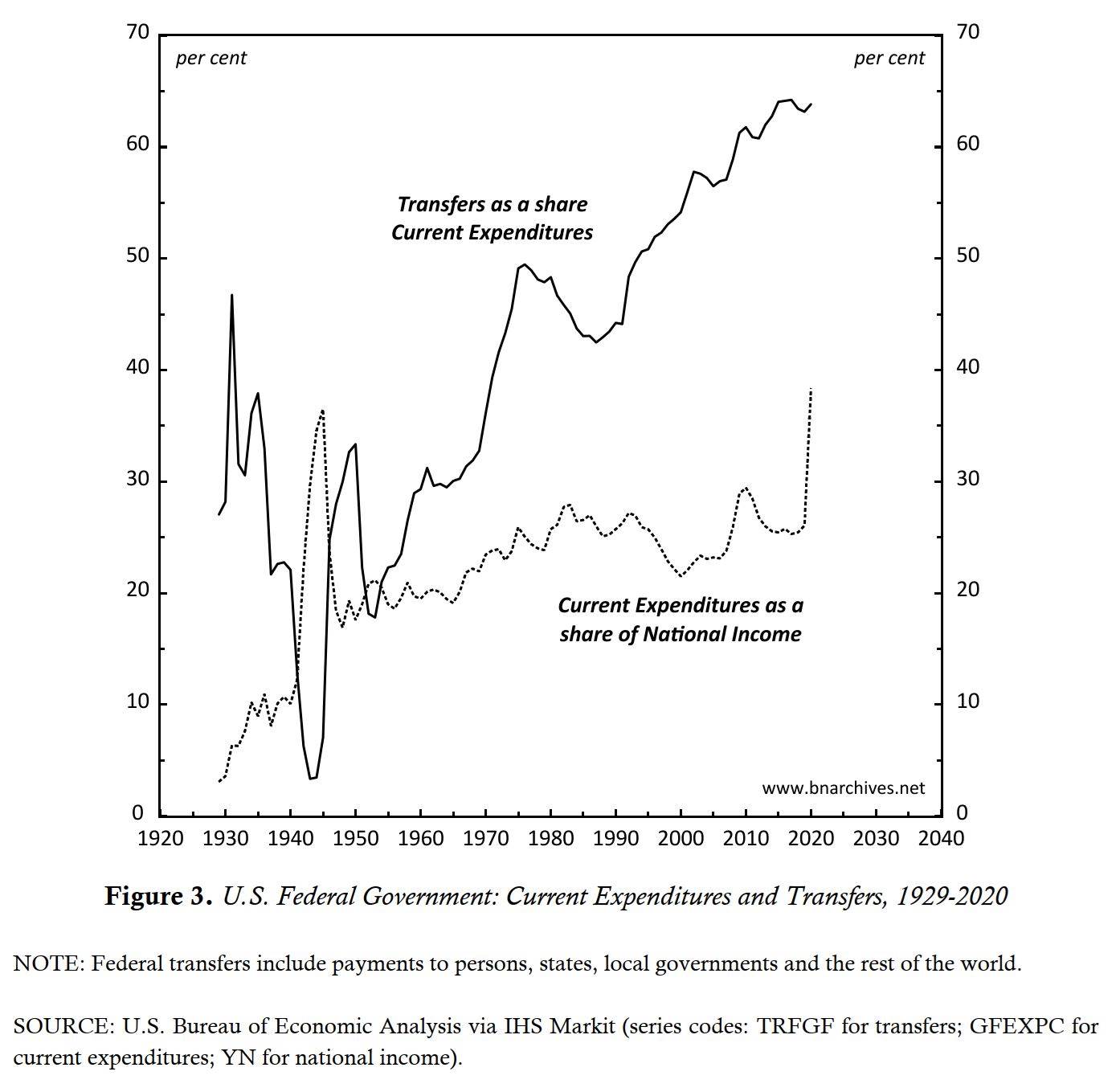

Figure 3 shows the changing importance of federal transfer payments in the United States. The dashed series depicts the level of current expenditures by the federal government, expressed as a share of U.S. national income. Note that these expenditures include purchases of goods and services, as well as transfer payments for which no goods and services are rendered in return. The solid series displays the share of transfer payments in overall current federal expenditures.

The relationship between the two proportions is telling. Initially, the association was negative. During the 1930s and 1940s, when the national income share of current federal expenditures increased, the share of transfers in these expenditures declined – and vice versa when government expenditures fell. This inverse relationship means that transfers were relatively stable, and that most of the ups and downs in federal spending were due to ups and downs in current government consumption.

But soon enough the relationship flipped. From the 1950s onward, the national income share of current federal expenditures trended upward – and, for the most part, this uptrend was driven by a relentless increase in the share of transfers. All in all, during the postwar era, this share rose 13-fold – from less than 5 per cent in the early 1940s, to nearly 65 per cent presently.

With this observation in mind, it is perhaps worth noting that the 2020 Covid19-related surge in current federal spending – a surge that many like/hate to think of as active ‘Keynesianism’ – was accounted for mostly by passive transfers.

The gradual shift from discretionary expenditures on goods and services to reactive transfers is typical of many governments around the world, and it suggests that these governments are far less potent than their size might imply. In fact, one can argue that the bigger ‘transfer states’ of today are far weaker than the smaller ‘consumption states’ of the Keynesian era. Their apparent largess indicates not greater power but subjugation: a built-in deference to dominant capital, whose strategic sabotage must be offset, at least in part, by unemployment insurance benefits, welfare payments and the like.

- Summary

On paper, the U.S. government is free to legislate its path and determine its policies. In principle, there is little to prevent a resolute U.S. administration from challenging the power of the country’s dominant capital and clip the wings of its largest firms.

But it would be good to remember that the U.S. government – like most other governments – has become part and parcel of an increasingly global state of capital. This integration has undermined the de facto autonomy of governments everywhere. Whether willing or reluctant, many if not most policymakers have become pawns of a global mode of power they cannot control and that forces them to tranquilize the increasingly vulnerable population that dominant capital helps create. Government spending has inflated, but this inflation betrays weakness, not strength.

Larger-yet-weaker neoliberal governments are the alter-ego of bigger-and-meaner dominant capital. It is hard to think of any important sector or aspect of society, in the United States and elsewhere, where dominant capital does not dominate. It is true that, faced with increasing resistance, the rising power of dominant capital in the United States has slowed down significantly over the years and seems to have stalled completely in recent times (Figure 1). But the level of this power is still greater than ever, and it is yet to show any meaningful decline. Finally, and importantly, the stalling advance of U.S. dominant capital makes it extra vigilant against any serious challenge.

Prediction: if the current U.S. government delivers on its promise to curtail the might of the country’s largest corporations, it will face the wrath of the most powerful megamachine the world has ever seen.

Endnotes

[1] Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan teach political economy at colleges and universities in Israel and Canada, respectively. All their publications are available for free on The Bichler & Nitzan Archives (http://bnarchives.net). Work on this note was partly supported by SSHRC.

References

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 2012. The Asymptotes of Power. Real-World Economics Review (60, June): 18-53.

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 2016. A CasP Model of the Stock Market. Real-World Economics Review (77, December): 119-154.

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 2020. The Limits of Capitalized Power. A 2020 U.S. Update. Working Papers on Capital as Power (2020/06, December): 1-16.

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 2021. Corporate Power and the Future of U.S. Capitalism. Real-World Economics Review Blog, January 4.

Doctorow, Cory. 2021. End of the Line for Reaganomics. Capital as Power Blog, September 26.

Fix, Blair. 2021. How Dominant are Big US Corporations? Economics from the Top Down, September 29.