From Blair Fix I recently had a lively Twitter debate with Jonathan Nitzan, Shimshon Bichler and Cory Doctorow1 about the future of big corporations in the United States. The debate was prompted by Doctorow’s piece ‘End of the line for Reaganomics’, which I reposted on capitalaspower.com. Doctorow argues that we may be witnessing a sea change in the way governments treat big corporations. Since the Reagan era, the US government has taken most of the teeth out of antitrust enforcement. The reason is not well known. In fact, I’m ashamed to admit that as a trained political economist, I didn’t learn this antitrust history in grad school. I learned it from Doctorow’s blog. In Bork we trust The antitrust story revolves around a judge named Robert Bork, who came up with a way to defang

Topics:

Editor considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from Blair Fix

I recently had a lively Twitter debate with Jonathan Nitzan, Shimshon Bichler and Cory Doctorow1 about the future of big corporations in the United States. The debate was prompted by Doctorow’s piece ‘End of the line for Reaganomics’, which I reposted on capitalaspower.com.

Doctorow argues that we may be witnessing a sea change in the way governments treat big corporations. Since the Reagan era, the US government has taken most of the teeth out of antitrust enforcement. The reason is not well known. In fact, I’m ashamed to admit that as a trained political economist, I didn’t learn this antitrust history in grad school. I learned it from Doctorow’s blog.

In Bork we trust

The antitrust story revolves around a judge named Robert Bork, who came up with a way to defang antitrust law by changing how it was interpreted. His 1978 book The Antitrust Paradox argued that antitrust law should be interpreted narrowly in terms of ‘consumer welfare’. And ‘consumer welfare’, in turn, meant one thing: low prices.

To make an antitrust case, Bork argued that you needed to show that the offending firm had used its monopoly power to raise prices. Moreover, you needed to demonstrate that government intervention would do more good than harm. The paradox, according to Bork, was that by interfering in the ‘free market’, antitrust prosecution tended to protect inefficient firms from competition, and so led to higher prices.

From a scientific standpoint, Bork’s arguments are a flaming pile of garbage. But they are fiendishly clever ideology. Once judges were indoctrinated in the Borkian worldview, it became nearly impossible to successfully prosecute an antitrust case. The problem is simple: if a sector is monopolized, you cannot tell what the prices would be if the sector was not monopolized.

Take, for example, big tech companies like Google and Facebook, which dominate the market for online advertisements. Do these companies use their power to set prices? Absolutely. Can we tell what advertising prices would be in a ‘competitive’ market? Absolutely not.

Sure, we can speculate about these prices. We can even run models. But once we start doing that, antitrust law devolves into an obscure exercise in model building. In other words, it enters the terrain of neoclassical economics, where absurd assumptions get buried in a wall of math, and where the outcome can be tweaked to give the results you want. Whoever can hire the most model-building economists wins. When you play that game, deep-pocketed corporations are almost always victorious. And so as Bork’s ideas became widespread (in the 1980s), antitrust law all but died.

Fortunately, Doctorow notes, there are signs that things are changing. The Biden administration has put antitrust proponent Lina Khan in charge of running the FTC. Under her watch, the government has launched a major antitrust case against Facebook.

That’s the good news. The bad news is that the judiciary remains indoctrinated in the Borkian worldview. In June 2021, justice James E. Boasberg threw out the Facebook case, arguing that prosecutors had failed to provide evidence that Facebook was a monopolist. Channelling Borkian ideology, Boasberg wrote:

It is almost as if the agency expects the Court to simply nod to the conventional wisdom that Facebook is a monopolist. After all, no one who hears the title of the 2010 film “The Social Network” wonders which company it is about. Yet, whatever it may mean to the public, ‘monopoly power’ is a term of art under federal law with a precise economic meaning.

(my emphasis)

What Boasberg actually means is that under federal law, ‘monopoly power’ has a precise ideological meaning that differs from the common-sense view held by the public. Hence, what seems like an obvious monopoly to the average person is, in the eyes of the law, a ‘competitive market’.

Legal setbacks aside, Doctorow remains optimistic that antitrust law is poised to regain its teeth.

A tight grip on power

Alright, that’s Doctorow’s take. Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler then entered the Twitter debate backed by their own research on corporate power. For their part, Nitzan and Bichler are less optimistic that the US government will seriously challenge the power of big corporations.

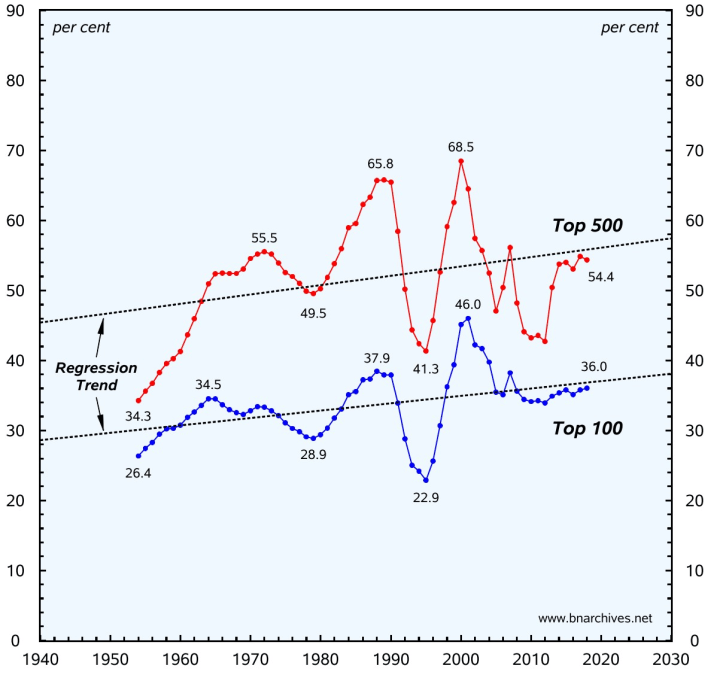

Here’s their reasoning. By several metrics, corporate power has tracked upwards over the last 70 years. Figure 1 shows Bichler and Nitzan’s analysis of profit concentration in the United States. The blue line shows the share of profits earned by the top 100 US corporations (ranked by market capitalization). The red line shows the profit share of the top 500 US corporations. Both measures of concentration have trended upward since data began in 1950.

While this trend is worrying, Bichler and Nitzan argue that it actually understates the growth of corporate power. That’s because at the same time that big corporations have become more profitably, small corporations have struggled. So relative to the average level of profit, big corporations’ grip on power has grown to astonishing levels.

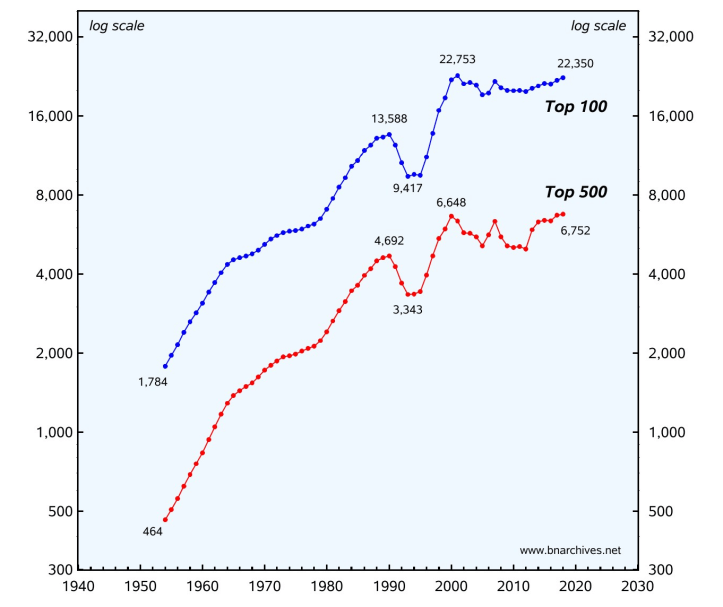

Figure 2 shows this alternative measure of corporate power. The blue line compares the average profits of the top 100 US corporation (ranked by market capitalization) to the average profits of all US corporations. The red line shows the same ratio, but measures the profits of the top 500 corporations. Both metrics have increased by more than an order of magnitude since 1950.

Looking at this data, Bichler and Nitzan argue that big corporations are more powerful than ever. So although the Biden administration may talk about enforcing antitrust law, Bichler and Nitzan think that the government is unlikely to put a serious dent in the power of dominant firms.

Big corporations vs. big government

Here’s where I enter the debate. I am more optimistic than Bichler and Nitzan that the US government will challenge corporate power. The reason is that the COVID crisis has forced a drastic change in government policy. Let’s have a look.

What I think is missing from Bichler and Nitzan’s analysis is government itself. Their data shows that when judged against the average company, top corporations are shockingly powerful. What this data does not show, however, is that big corporations have government under their thumb. To make the case for the corporate dominance of government, we need to analyze government behavior.

One option is to look at government policy and determine whether it is pro-big-business or not. That’s a messy job that I’ll leave for a later date.

The other option is to simply measure the size of government and see how it compares to the size of big corporations. This size gives us a sense of the tug-of-war between the public and private sector. It’s not a perfect indicator, since government spending can be channelled into private-sector coffers (that’s what the Pentagon does). Still, when the government spends money, it is using its power to shape society.

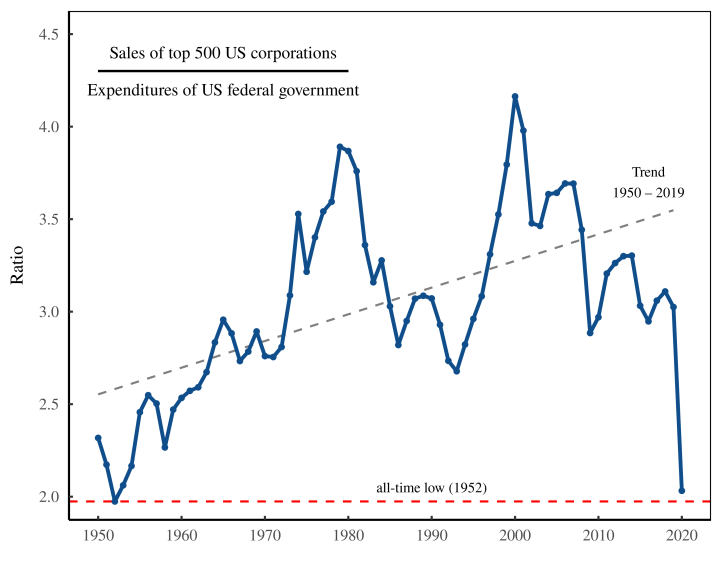

With that in mind, I’m going to compare the sales of top US corporations to the expenditure of the US federal government.2 Think of this comparison as a measure of corporate power relative to government power. If big US corporations have government under their thumb, we expect this metric to increase. And indeed it has.

Figure 3 shows trend in the United States. I’ve plotted here the ratio between the sales of the top 500 US firms (ranked by sales) and the expenditure of the US federal government. From 1950, corporate power trended upwards, as indicated by the dashed grey line.

The steady creep of corporate power (from 1950 to 2019) elicits a feeling of inevitability. And had 2020 been a ‘normal’ year, corporate power might have continued to increase. But 2020 was not a normal year. It was the year of COVID. While there is little to love about the COVID pandemic, it did demonstrate something important: society is the way we make it.

It is our collective ethos that determines the balance of power between big corporations and government. Yes, the ethos can seem inevitable. And under ‘normal’ circumstance, it is difficult to change. That’s why for the last half century, big corporations increasingly dominated society, all the while championing the ethos of ‘free markets’. But we should not forget that an ethos can change, sometimes in a shockingly short time.

And that, I believe, is what we are witnessing in Figure 3. In a single year — 2020 — the corporate grip on power was reversed to levels not seen since 1952. We all know what happened. Faced with the need to keep people home but not have them starve, governments around the world went on spending sprees so massive that they would make JM Keynes blush.

While we can debate the effectiveness of this spending, what seems clear is that it constitutes a cataclysmic shift in our collective ethos. Talk about free-market competition was suddenly dominated by talk about social welfare. As David Graeber put it, COVID woke us from a collective dream:

[t]he crisis we just experienced was waking from a dream, a confrontation with the actual reality of human life, which is that we are a collection of fragile beings taking care of one another, and that those who do the lion’s share of this care work that keeps us alive are overtaxed, underpaid, and daily humiliated, and that a very large proportion of the population don’t do anything at all but spin fantasies, extract rents, and generally get in the way of those who are making, fixing, moving, and transporting things, or tending to the needs of other living beings.

My take, then, is that Doctorow’s optimism is justified. Yes, Bichler and Nitzan are correct that big corporations became increasingly powerful over the last half century — a period during which the public sector was beaten into submission by private power. And until 2020, the growth of corporate power looked inevitable. But it was not. The last year has shown that society is what we make it. If we want pro-social spending that shirks the doctrine of free markets, we can have it.

The last year has been surreal in so many ways. Stock markets are up. Unemployment reached levels not seen since the Great Depression. And yet the poverty rate actually fell. That’s the funny thing about giving people money. It makes them unpoor.

Moreover, widespread eviction moratoriums relieved the burden of paying rent. By so doing, they laid bare the facts of property rights. There is no ‘natural law’ that says landlords should earn money from their property. No, that stems from the human-made law of property rights. And guess what … if the government stops enforcing that law, property income vanishes.

Whether all the changes that COVID has wrought will last is anyone’s guess. And whether these changes will translate into robust antitrust policy is unknown. But I prefer to remain hopeful that pro-social change is possible.