In September 2021, a Dutch judge decided, in a case of the FNV Union against Uber, that Uber drivers are employees, not dependent or independent contractors. Meaning, on the micro level, that these employees in one stroke were entitled to more money, more protection and more rights. In the macro-conceptual framework of the International Labour Organization (ILO) this means that they shifted from a somewhat informal status to a formal status (see below). While it shows up, in the conceptual framework of the economist Guy Standing, as a shift from the ‘precariat’ towards the ‘salariat’: “the old salaried class has splintered into two groups: the salariat, with strong employment security and an array of non-wage forms of remuneration, and a small but rapidly growing group of

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

In September 2021, a Dutch judge decided, in a case of the FNV Union against Uber, that Uber drivers are employees, not dependent or independent contractors. Meaning, on the micro level, that these employees in one stroke were entitled to more money, more protection and more rights. In the macro-conceptual framework of the International Labour Organization (ILO) this means that they shifted from a somewhat informal status to a formal status (see below). While it shows up, in the conceptual framework of the economist Guy Standing, as a shift from the ‘precariat’ towards the ‘salariat’:

“the old salaried class has splintered into two groups: the salariat, with strong employment security and an array of non-wage forms of remuneration, and a small but rapidly growing group of proficians. The latter, which includes small-scale businesses, consists of workers who are project-oriented, entrepreneurial, multi-skilled, and likely to suffer from burn-out sooner or later. Traditionally, the next income group down has been the proletariat, but old notions of a mass working class are out-dated, since there is no common situation among workers. The earlier norm of this diminishing male-dominated class was a lifetime of stable full-time labor, in which a range of entitlements called “labor rights” was built up alongside negotiated wages. As the proletariat shrinks, a new class is evolving—the precariat”.

Source: Standing, G. (2014) ‘The precariat’, Contexts 13-4, pp. 10-12.

Source: ILO (2021), Conceptual Framework for Statistics on the Informal Economy (Geneva) p. 48.

Official statistics (the ILO is the main powerhouse for conceptualizing new labor statistics) as well as academic discourse are moving to encompass recent developments on the labor market. The question here: are these endeavors, one (ILO) mainly using juridical and institutional delineations while the other (Standing) also looks at alienation, exploitation and class struggle, compatible? According to me, the answer is yes. Let me explain why.

Both the ILO and Standing thy to develop, broaden and enrich the present macro labor statistics. And even when ‘informal labor’ is not the same thing as ‘precarious labor’ I do think that the concepts as well as the motives to conceptualize and operationalize these concepts overlap. .In 2020 and 2021, the International Labour Organization (ILO) has organized and hosted some conferences on how to measure informal labor. This is no coincidence: the ILO is the ‘go to place’ for statisticians when it comes to conceptualizing and operationalizing labor statistics. Contrary to some other sciences, questions of conceptualizing and operationalizing macro economic variables are not answered by academic economists but ‘left’ to statistical agencies, in case of labor statistics the ILO. This is slightly dull and dreary. The ILO working paper I linked to starts with: “it is based on the discussions that took place during the second meeting of the International Labour Organization (ILO) Working Group for the Revision of the standards for statistics on informality in 2020 (ILO, 2021a) as well as the discussions in the four subgroups of the Working Group established following the meeting. The paper can be viewed as an update or continuation of the discussion paper Conceptual Framework for Statistics on Informality (ILO, 2020a) which was presented and discussed at the second meeting”. To conceptualize the concept of informality the ILO uses the SNA production boundary (the ‘money economy’ of the national accounts) as well as the SNA general production boundary (the national accounts economy plus household production of goods and services for own use plus communal production of goods and services for use of the community). Which enables us to tie it to the statistics of employment and unemployment (which are based upon the ‘money economy’) but also to broader concepts of production, as well as to national accounts production and productivity. Also, lemma 320 and 321 (of 323) of the ILO report state: “The fourth dimension, Contextual vulnerability, includes indicators that provide further context on the degree of informality and formality, degree of protection for informal and formal workers as well as vulnerabilities and protection at the household level. This dimension is important in order to contextualize the situation of informal and formal workers and to create a more in-depth understanding of the exposure to risks that informal and formal workers are facing as well as regarding the drivers behind informality. The fourth dimension is expected to include indicators that are typically less frequently included in 83 statistical sources and could therefore be recommended to be compiled with less frequency and depending on the needs and objectives for measurement … The fifth dimension, Other structural factors, includes the possibility to carry out a legal mapping of enterprises and workers according to the national legal and regulative scope of the formal arrangements. This allows an assessment of whether the source of informality is due to a lack of legal coverage or a lack of effective coverage, which can provide important input for the design of policies addressing informality. Thus this dimension is partly based on qualitative as well as quantitative indicators and could be produced with less frequency, depending on the countries need and objectives. It includes also the assessment of other structural factors of informality associated to the structure of employment (e.g. prevalence of certain status in employment and sectors) and to the composition of growth.”

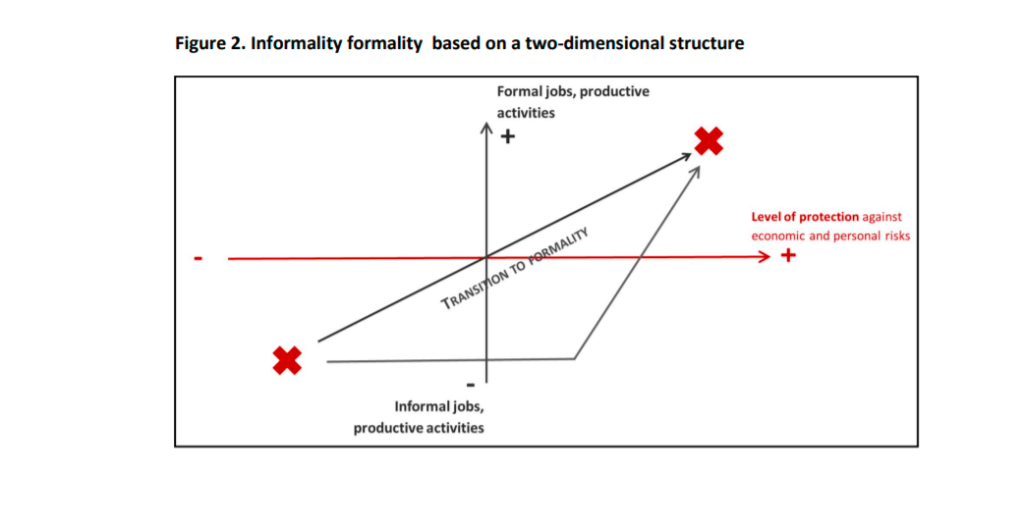

Which means that the decision of the Dutch judge is totally compatible and can be tackled with this conceptual framework. As is shown by the graph on p. 81 on the ILO report:

Now, Standing does add a third dimension to this: alienation. And puts it in a political, class struggle context. At the same time, precarious workers in the sense of Standing can be entirely formal. Even when his idea that the labor of precarious workers often requires a lot of ‘work’, i.e. a lot of unpaid activities like travelling but also work preparation have to be carried out before the worker can start with gainful employment – informal elements of formal jobs. But the point: exiting things are happening, at the ILO and at universities: ever better conceptualization and operationalization of new kinds of work, sometimes in an outright political economy perspective and sometimes in a sightly tamer but compatible institutional framework. Neoclassical economists came up with the unmeasurable concept of NAIRU: the Non Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (or, in Europe, with NAWRU – never mind). Let’s forget about that and move towards what we can measure: vulnerabilities, informality, exploitation and alienation, in a macro framework tied to the money economy as well as to a broader concept of production and distribution.