From Blair Fix and current RWER issue A key problem with eugenics is that it neglects the social nature of human traits. It assumes that productivity is an innate trait of the individual, and that breeding for this trait would lead to a better society. It is a seductive idea that is deeply flawed. In all likelihood, selectively breeding people for productivity would, like chickens, lead to a psychopathic strain of human. The rise of human capital theory After the horrors of the Holocaust, eugenics fell into disrepute. As a result, few people today dare argue that we should selectively breed humans for productivity. Still, the sentiment behind eugenics (that some people are far more productive than others) lingers on in mainstream academia. It survives – even thrives – in human capital

Topics:

Editor considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from Blair Fix and current RWER issue

A key problem with eugenics is that it neglects the social nature of human traits. It assumes that productivity is an innate trait of the individual, and that breeding for this trait would lead to a better society. It is a seductive idea that is deeply flawed. In all likelihood, selectively breeding people for productivity would, like chickens, lead to a psychopathic strain of human.

The rise of human capital theory

After the horrors of the Holocaust, eugenics fell into disrepute. As a result, few people today dare argue that we should selectively breed humans for productivity. Still, the sentiment behind eugenics (that some people are far more productive than others) lingers on in mainstream academia. It survives – even thrives – in human capital theory.

The ground work for human capital theory was laid just as eugenics fell out of favor. In the 1950s, economists at the University of Chicago tackled the question of individual income.[1] Why do some people earn more than others? The explanation that these economists settled on was that income resulted from productivity. So a CEO who earns hundreds of times more than a janitor does so for a simple reason: the CEO contributes far more to society.

The claim that income stems from productivity was not new. It dated back to the 19th-century work of John Bates Clark (1899) and Philip Wicksteed (1894), founders of the neoclassical theory of marginal productivity.[2] Clark and Wicksteed, though, were concerned only with the income of social classes. What the Chicago-school economists did was expand productivist theory to individuals.

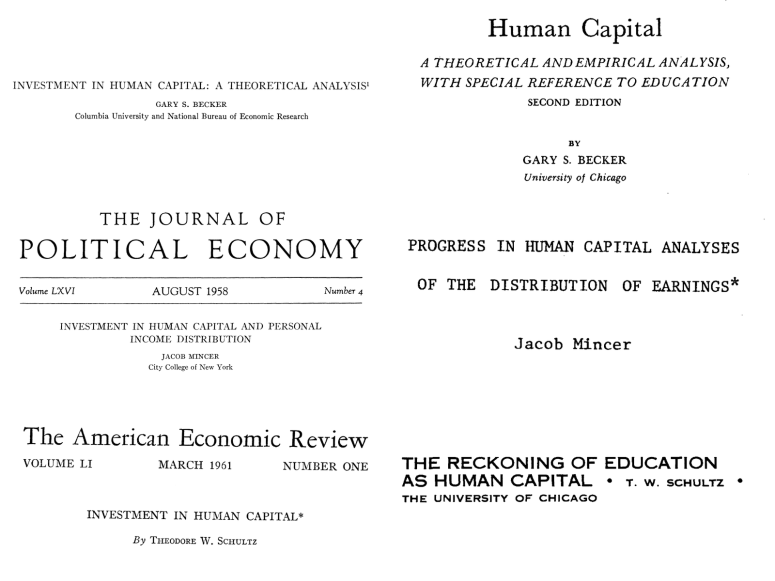

oing so required inventing a new form of capital. The idea was that individuals’ skills and abilities actually constituted a stock of capital – human capital. This stock made individuals more productive, and hence, earn more income. Figure 3 shows key papers that initiated human capital theory.

Figure 3. Key papers that initiated human capital theory

The theory of human capital began in the late 1950s and early 1960s with papers by Chicago-school economists Gary Becker, Jacob Mincer, and Theodore Schultz. Pictured here from top to bottom: Becker (1962) and the 2nd edition of Becker (1964); Mincer (1958) and Mincer (1974); Schultz (1961) and (1970).

The idea that skills constituted “human capital” was initially greeted with skepticism. For one thing, the term itself smacked of slavery. (Capital is property, so “human capital” implies human property.) For another, human capital theory overtly justified inequality. It implied that no matter how fat their incomes, the rich always earned what they produced. Any attempt (by the government) to redistribute income would therefore “distort” the natural order. During the 1950s and 1960s, there was little tolerance for such views. It was the era of welfare-state expansion, driven by Keynesian-style thinking. Yes, big government may have been “distorting” the free market – but society seemed all the better for it.

Until the 1970s, human capital theory remained obscure. But then politics began to change. In the words of Ronald Reagan, “People were tired of wasteful government programs and welfare chisellers” (1990). The welfare system was not a social safety net, Reagan declared. It was a “creator and reinforcer of dependency” (1987). Reagan’s language, you will note, is eerily similar to the eugenics sentiment of old:

“Some people are born to be a burden on the rest.”

Yes, Reagan removed the crass genetic component. But the sentiment remained the same:

“Some people are a burden on the rest.”

The stage was set for a return to eugenics-style thinking – to the idea that the poor were a burden on the rich (not the other way around). As a result, the fortunes of human capital theory rose.

[1] It is no coincidence that human capital theory arose out of the University of Chicago. The school was established in 1890 with a $600,000 donation from John D. Rockefeller. In return, the school became a bastion of neoclassical economics. Rockefeller later described his donation as “the best investment I ever made” (Collier & Horowitz, 1976; quoted in Nitzan & Bichler, 2009).

[2] We can go further and trace productivist sentiment back to the 17th-century philosopher John Locke, who argued that property comes from the exertion of productive labor (Locke, 1689).