From Dean Baker There has been much press around President Biden’s demands that China not support Russia in its invasion of Ukraine. The implication of these demands is that the United States has the ability to punish China economically in a way that imposes more pain on China than on us. That may be true for now, but it’s not clear it will be true much longer, and it may not even prove to be true at present. It is common to refer to China as the world’s second largest economy, after the United States. However, using a purchasing power parity measure, China’s GDP actually passed US GDP in 2016. The IMF projects that it will be more than one third larger by 2026, the last year of its projection period. Source: IMF The purchasing power parity measure, in contrast to the more commonly

Topics:

Dean Baker considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from Dean Baker

There has been much press around President Biden’s demands that China not support Russia in its invasion of Ukraine. The implication of these demands is that the United States has the ability to punish China economically in a way that imposes more pain on China than on us. That may be true for now, but it’s not clear it will be true much longer, and it may not even prove to be true at present.

It is common to refer to China as the world’s second largest economy, after the United States. However, using a purchasing power parity measure, China’s GDP actually passed US GDP in 2016. The IMF projects that it will be more than one third larger by 2026, the last year of its projection period.

Source: IMF

The purchasing power parity measure, in contrast to the more commonly cited exchange rate measure, applies a common set of prices for all the goods and services produced in both economies. Most economists view purchasing power parity measures as a better measure of the strength of an economy, since it is measuring what is actually produced. The exchange rate measure can fluctuate hugely as a country’s currency moves up or down in financial markets. It also will understate a country’s GDP if it is deliberately holding down the value of its currency.

It is worth noting that on a per capita basis China is still much poorer than the United States. It has nearly four times as many people, so its per capita GDP is still less than one-third of the per capita GDP in the United States. Nonetheless, its economic power in the world depends more on its overall GDP than its per capita GDP.

This fact means that Biden is effectively threatening an economy with a bigger GDP than the United States. Any major economic sanctions, such as a sharp reduction in imports, will have large negative effects on the US economy as well, especially in the context of an economy that is still unwinding the supply chain disruptions caused by the pandemic.

The United States would be helped in this sort of confrontation by the fact that Biden can likely count on the support of wealthy allies in Western Europe and Japan, as well as pockets elsewhere in the world. Adding in the economies of US allies, Biden can still command an economic bloc that is larger than China.

But, it is important to remember that China also has allies. This list includes major Asian countries such as Pakistan and Iran, as well as many countries throughout Africa and Latin America, who resent the way the United States and West Europe have treated them over the last two hundred years.

For now, Biden’s economic bloc is almost certainly larger than Xi’s, but that still doesn’t mean that he is better positioned to impose economic pain on China than the other way around. As best we can tell, Xi doesn’t have to worry about opposition within China, at least as long as he isn’t facing a complete economic collapse.

By contrast, we can be absolutely certain that the Republican Party will jump on every price increase and shortage that results from any sanctions imposed by Biden or Chinese counter measures. The Republican attacks will also be supported by most media outlets, who will either embrace them wholeheartedly or do a he said/she said that leaves it to their audience to determine whether economic pain is due to Biden’s inept management of the economy or his efforts to punish China. Given that the political consequences likely mean defeat in the 2022 and 2024 elections for Biden and the Democrats, it is not clear Biden has the better position in an economic confrontation with China.

Getting Beyond Russia’s Invasion

If we can envision a world after the invasion has been resolved in some manner, we will still have major choices to make on our relationship with China. There are many who would like to maintain a stance of confrontation similar to our relationship with the Soviet Union in the Cold War. That is a story that is not likely to turn out well for the United States or the world.

As noted above, China’s economy is already larger than the US economy and the gap will, in all probability, grow considerably in coming decades. This means that the story that we can build up our military and spend China into the ground, which we arguably did with the Soviet Union, simply is not plausible.

We are more likely to spend ourselves into the ground in that story. We need a different strategy. Rather than one of ongoing confrontation, we need one of selective cooperation, where we work with China where we have clear common interests.

The most obvious places where common interests exist is with climate change and health care. The United States, China, and the whole world would benefit from shared and open research in these areas, so that the whole world can quickly adopt innovations, wherever they occur.

This would imply some sort of international agreement on committing funds for research, based on countries’ size and wealth. The details of such an agreement would be contentious, but those who have failed negotiations on the Trans-Pacific Partnership and other trade deals know that negotiations on the current system of intellectual property rules are also very contentious.

There would be enormous benefits from having all new climate technologies transferred at zero cost, without the markups for government-granted patent monopolies or related protections. This should hugely accelerate the pace at which clean energy and electric cars are adopted.

There is a similar story with medical technologies. Without government-granted monopolies, nearly all drugs, vaccines and medical equipment would be cheap.[1] All but the poorest people in the world would find them affordable, and meeting the needs of the poor would be a doable task for international aid organizations.

Protecting “Our” Intellectual Property

When I propose this route in dealing with China, I almost invariably encounter the complaint that we are giving away our intellectual property. This indicates some very serious confusion.

The intellectual property at issue does not belong to any “us,” it belongs to Bill Gates, Pfizer, and Moderna, which has created at least five billionaires since the beginning of the pandemic. In fact, our system of patents and copyrights has been a major cause of the growth in inequality over the last four decades.

It would be incredibly foolish, from a progressive perspective, if we were to confront China in order to protect this antiquated and inequitable system. Bizarrely, rather than contesting intellectual property rules that increase inequality, many are looking to regain manufacturing jobs that were lost to trade with China and other countries, in the last few decades.

This strategy is bizarre because it ignores the changes in the quality of manufacturing jobs over this period, in large part due to trade. Four decades ago, manufacturing was a heavily unionized sector. As a result, jobs in manufacturing paid considerably more than jobs in other industries.

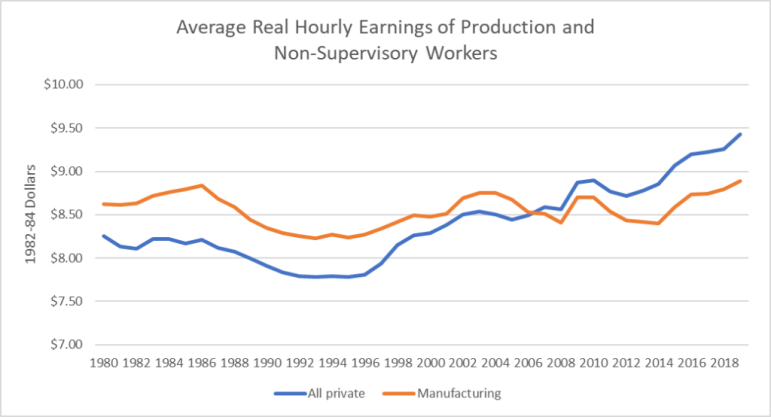

This is no longer true. The unionization rate in manufacturing is only slightly higher than the unionization rate in the private sector as a whole. The wage premium in manufacturing has largely disappeared.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

If progressives were to embrace a path of confrontation with China, that has protection of intellectual property at its center, in exchange for some not especially good jobs in manufacturing, it would be a real lose-lose-lose story for anyone who cares about inequality and peace. We really should not go down that route. It is important that we can have a serious discussion on these issues now.

[1] Nondisclosure agreements, which allow companies to protect industrial secrets, would be unenforceable on publicly funded research in these areas.