Are we living in an epoch of high inflation? it’s a difficult question to answer as we’re lacking the tools to do this. Economics – heterodox and mainstream alike – is lacking a profound ‘periodic table’ of prices. This hampers them when they write and talk about inflation. There are a lot of pieces to this puzzle. The framework of the national accounts provides us with the distinction between expenditure prices (investments, government purchases, household consumption, exports), factor prices (wages, rents) and producer prices, including and excluding taxes. Gardiner Means developed the idea of ‘administered’, in-company prices. Joan Robinson made practical distinctions between prices and systems of price-setting: monopsony, imperfect competition and the like. And there is,

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

- Are we living in an epoch of high inflation? it’s a difficult question to answer as we’re lacking the tools to do this. Economics – heterodox and mainstream alike – is lacking a profound ‘periodic table’ of prices. This hampers them when they write and talk about inflation. There are a lot of pieces to this puzzle. The framework of the national accounts provides us with the distinction between expenditure prices (investments, government purchases, household consumption, exports), factor prices (wages, rents) and producer prices, including and excluding taxes. Gardiner Means developed the idea of ‘administered’, in-company prices. Joan Robinson made practical distinctions between prices and systems of price-setting: monopsony, imperfect competition and the like. And there is, of course, the distinction between market prices (which are set before a transaction is finalized) and non-market prices, which are not part of a market transactions (like the already mentioned ‘administered’ prices or, in the Netherlands, the ‘rekenrente’ interest rate set by the central bank and which pension funds have to use to calculate the present value of their obligations. Somebody has to come up with such a ‘periodic table for prices’.

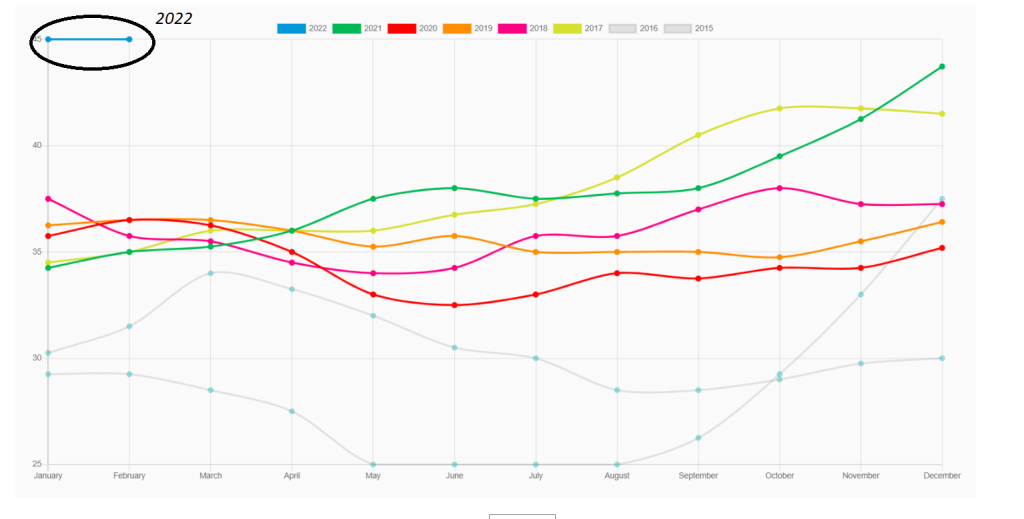

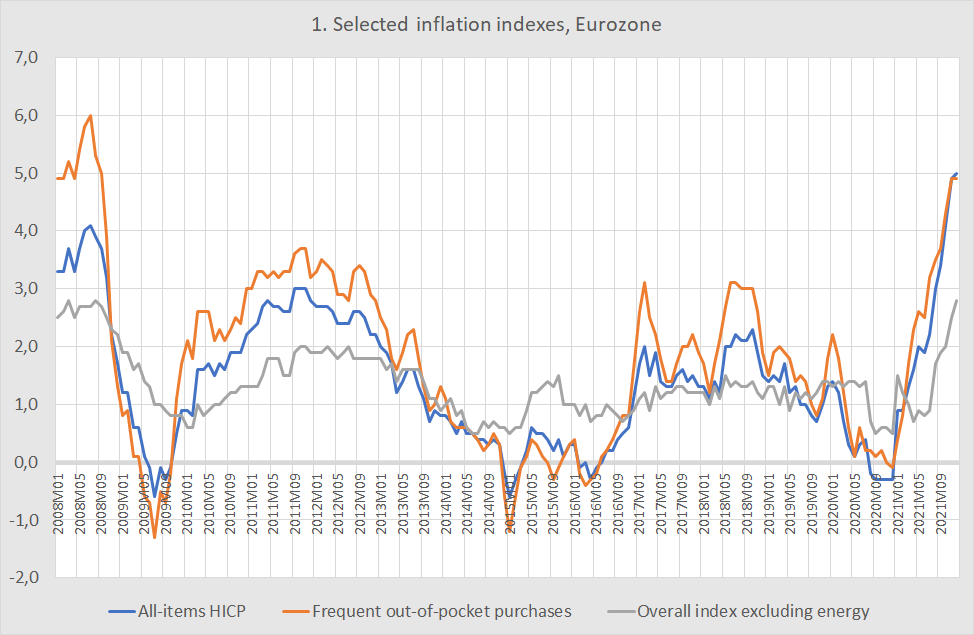

- Having stated this, it still is interesting to analyze inflation from a political economy perspective. First, the question has to be posed: “what is inflation”. Restricting us to Consumer Price Inflation the answer is relatively straightforward: “it is a calculated composite number which enables us to gauge the purchasing power of household income (wages, rents received, profits, transfer incomes)”. There are however many ways to do this, look here for the differences between the Dutch Consumer Price Index and the Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices (HICP)for the Netherlands. One crucial difference: the Dutch CPI uses imputed rents to calculate housing costs of house owners (the monetarist founders of the European Central Bank wanted an inflation metric which was as monetary as possible). Consumer prices are, partly as CPI inflation will influence wage negotiations, also seen as a metric of macro economic stability. Highly variable prices like energy prices are often left out of the index to make it serve this purpose. Also, behavioral economists point out that the ‘feel’ of inflation is influenced by items which are actually paid by consumers (Frequently Out Of Pocket Purchases) and have designed, using the HICP as a basis, FROOPP inflation. Importantly, all of these 4 (!) consumer price indexes use the same basic classification of goods (developed for national accounting). The first graph shows that all kinds of consumer price inflation are increasing, even when the difference between ‘core’ inflation and ‘headline’ and FROOPP inflation is exceptionally large. Inflation is not what you make it to be. But it does have many sides. And expenditure inflation has increased, quite a bit.

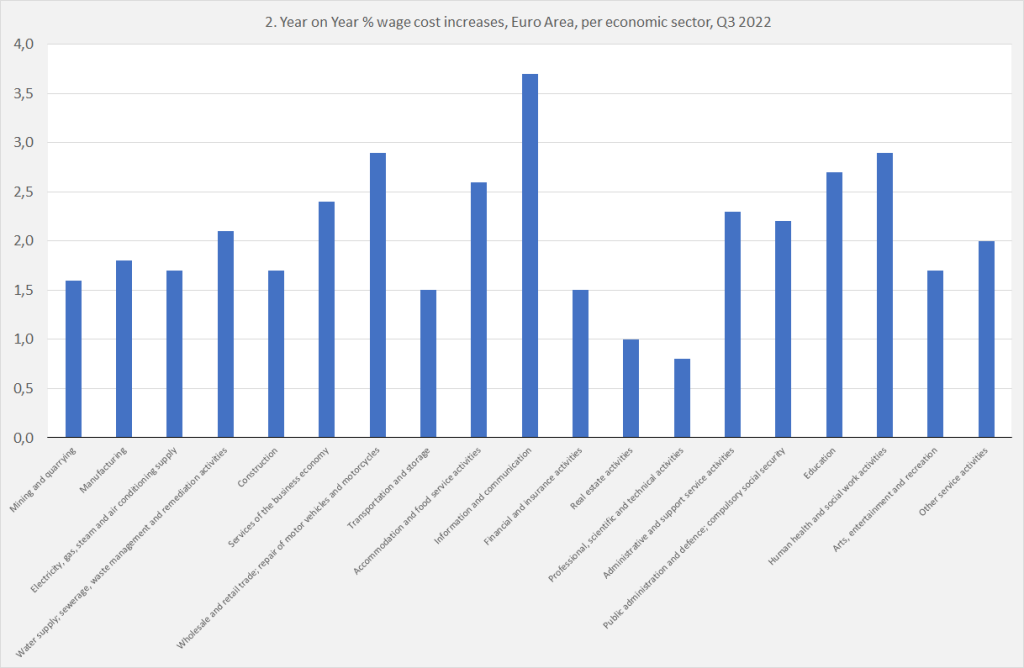

- But, ass stated, there is expenditure inflation and factor price inflation. Below, the development of wages per sector in the Eurozone is shown. High inflation is nowhere to be seen. Let’s make this clear: the economy consists of different realms, like the expenditure realm, the factor prices realm and the producer prices realm. During non epochs of non transitory high inflation prices will increase in all of these. At this moment, this is not happening. Actually there is quite some room to increase wages! Seen from this angle, we’re not living in an high inflation epoch. Not at all.

4. Still, consumer price inflation is high, which erodes purchasing power (see also graph 2). Where does this come from? There seem to be two main culprits. One is the price of fossil ‘fuels’. High prices for fossil are what we want as these will ease the transition to a low carbon economy. But even as they stay as high as they were during the last months of last year the influence on the price level will be permanent but the influence on inflation, which measures the increase of the price level, will be transitory. The contribution of fossils fuels to inflation is in fact already waning. Another culprit are food prices. This is more of a problem. Looking at producer prices of a major food like milk it shows that prices went through the roof. These are not market prices but administrated prices paid by the cooperative FrieslandCampina based on costs on one side and prices of outputs like cheese and yoghurt and the like on the other side. Milk prices are way more complicated than one would imagine (these prices also contain some renumeratioin for capital provided by farmers and are in fact prices for fat, protein, milk sugar and even ‘weidegang’, or keeping the cows outside). But the question: does this make farmers rich? Hmmm… they complain about high prices for feed, fertilizer and energy. Mind that producing chemical fertilizer is quite energy intensive. This suggests that there might be some kind of ‘finite earth’ inflation going on and the owners of the scarcest resource, ‘land’, eventually win. If so, inflation could, considering the rather inelastic nature of food demand, become quite a bit higher. While we might also see changes in production chains as peoples and companies owning this scarce resource might want to change the institutions governing price setting in their favor, at least as governments let them do this. Their ownership rights might however also be restricted, or sold (‘land grab’). This is very much a political question – as, hence, is inflation. Anyway – there sure is a chance that we entered an era of ‘finite earth inflation’, a kind of the reverse of the long term price decline of food products and other ‘land’ based products which started after the end of the USA civil war.

Graph 3. MIlk prices paid by the large dairy cooperative FrieslandCampina to members of the cooperative.