Summary: to understand inflation we should not use the neoclassical ‘one good, one worker, one sector, one piece of physical capital’ or Y = f(K,L) concept of production. We should use a concept looking at nominal production (Y(n)) with multiple interrelated sectors (‘S’), multiple products and capital conceptualized not as a physical entity but as ownership rights of land (including natural resources), depreciable capital and ‘non produced’ capital like patents and marketing rights: K’. These ownership rights enable as well as restrict access to and use of land, natural resources, depreciable capital, patents, markets and financial capital while the relations between sector show how shocks are propagated: Y(n) = f(S K’, L). Estimated models using such a concept exist and lead to

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

Summary: to understand inflation we should not use the neoclassical ‘one good, one worker, one sector, one piece of physical capital’ or Y = f(K,L) concept of production. We should use a concept looking at nominal production (Y(n)) with multiple interrelated sectors (‘S’), multiple products and capital conceptualized not as a physical entity but as ownership rights of land (including natural resources), depreciable capital and ‘non produced’ capital like patents and marketing rights: K’. These ownership rights enable as well as restrict access to and use of land, natural resources, depreciable capital, patents, markets and financial capital while the relations between sector show how shocks are propagated: Y(n) = f(S K’, L). Estimated models using such a concept exist and lead to quite another analysis of inflation than the neoclassical model.

Inflation, even when on the wane, is still unacceptably high.

A sudden increase of the energy bill of 200 Euro a month – and that’s only one of the price increases we’re talking about – means big and lasting problems for people with low and even median incomes. Household purchasing power is falling over a cliff as inflation is about 10% while the combination of employment growth and wage growth in the Eurozone will only be about 6% to 7%. Especially households which were not sell more labor will take a large hit. The European Central Bank tries to get inflation down in the only way they are able to, by increasing interest rates. This is based on an economic model which states that tight labor markets will lead to inflation meaning that labor markets have to become less tight – at this moment this model seems to be the only one they use. One can question such policies, as Paul Krugman does. He points out some real world anomalies (good!). As an alternative, he leads us to a model of Guerrieri, Lorenzoni and Straub who, according to him (and I think Krugman summarizes the argument in an apt way) ‘basically assume a big shift in the composition of demand, plus sluggish reallocation and downward wage and maybe price rigidity…What a model along these lines would predict is a jump in overall prices, with very high but temporary inflation in some sectors. Also a lot of churn as labor reallocated to expanding sectors’. It’s an expansion of the one sector neoclassical macro to a two sector model, with labor modelled a bit more precise than usual (jobs, hours and persons are supposed to be the same thing, but the authors at least state this clearly which not always happens, more about this here, chapter 4). It is, however, still only a 2 sector model, it has no foreign sector and it’s not estimated. We can do better, as Weber, Jauregui, Teixeira and Nassif Pires show. They present, using input-output tables based on national accounts data, an estimated model based on dozens of sectors, including (as they use the supply and use tables of the national accounts) ‘import’ and ‘export’. Their results? When we look at the last year it shows that inflation is generated ‘land’ related sectors (land including natural resources).

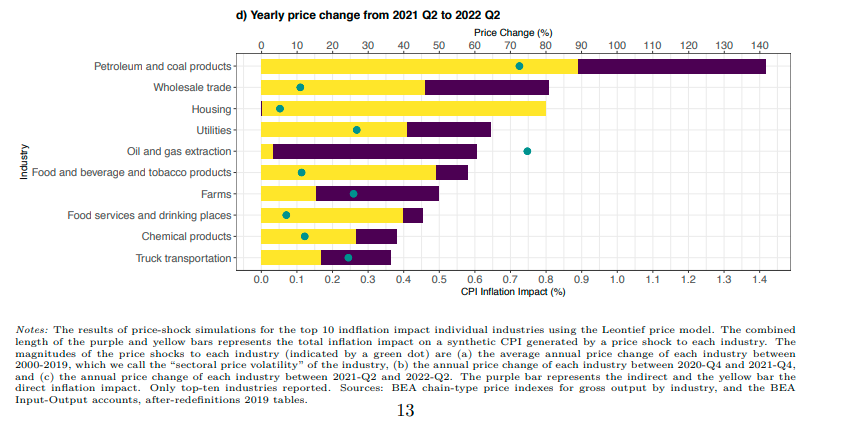

Graph 1. Contribution of different sectors to inflation according to Weber e.a., last year.

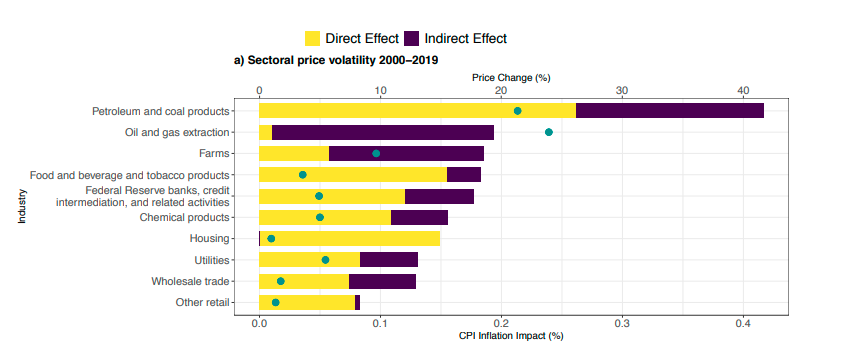

When we look at the last to decades, the same pattern shows (graph 2).

Graph 2. Contribution of different sectors to inflation according to Weber e.a., last two decades.

It are not labor intensive sectors with limited increases of productivity like education, construction or care which contribute most to price volatility. It are very much land intensive activities with a high capital coefficient like oil and gas extraction and oil refineries which contribute a lot. Mind: these contributions can be positive or negative. Energy prices have a large influence when they go up but also when they go down. But that’s the whole point. At this moment, there is a kind of ‘perfect inflation storm’ in which the direct effects (as they are measured in the consumer price index) and the indirect effects (changes in one sector which feed through to other sectors) of several systemic important sectors are high and positive (compare the scale of the x-axes). The large importance of capital (or to state this otherwise: a low labor share of value added and a high capital share) enables this. The capital share is very much a residual which, even when generally high, can and does fluctuate a lot, enabling large swings in prices. When, for whatever reason, several of these sectors experience ‘shocks’ enabling large price increases this might lead to a ‘perfect inflation storm’ – as we’ve seen last year.

The analysis shows that such a storm can be identified and analyzed, with obvious consequences for anti-inflationary policies. In the short run: sit down and wait when it comes to inflation, while supporting groups which are disproportionately hit. In the long run: invest in less dependence on global food and energy markets and supply chains and introduce market systems mitigating short term price changes by stabilizing the capital income share of sectoral value added. Here you can find, by Yanis Varoufakis, a convincing analysis how EU neoliberal energy market reforms did exactly the opposite (private energy companies with low average and marginal cost prices are allowed, in a complicated way and using some intra company transfers, to charge consumers the highest marginal prices of other producers, leading to outsized capital income). Having said this, it also has to be stated that it’s remarkable that EU countries are, at the same time, phasing out nuclear as well as production of natural gas (which in both cases is a clear choice). To an extent this is compensated by the unexpected strong growth and low cost price of solar and wind but that is a happy coincidence and de-growth is not the same thing as increasing external energy dependence. A somewhat comparable stories can be told for food. The Netherlands are the largest butter exporter in the world, the country is drowning in milk – but retail prices for dairy are going through the roof as prices are coupled to world market prices – which is a relatively new situation (since 2015). The Dutch lowered their coastal defenses, expecting that this would lead to a calmer sea. Hmmm… perfect storms do happen. Anyway, identifying the interrelations between sector in combination with an analysis of production and marketing rights and ownership of will enable the formulation of policies aimed at mitigating perfect storms. That’s what input-output analysis of inflation enables us to do.

Sad to say, such kinds of analyses are not new. Here, a 1985 Bureau of Labor Statistics input output study by Duggan and Clem using four factors of production: labor, capital, energy and materials with a conclusion which is highly consistent with the ideas of Weber et all. Look here for a 2022 study by Przybyliński and Gorzałczyński, again with results consistent with the ideas of Weber er all.In both cases fully estimated multi sector models, using input-output analysis. Krugman is right to spot anomalies and to push for multi-sector models. The point is: fully estimated multi-sector inflation models exist and are nothing new. We should have used them.