What’s money? Wrong question. The right question: ‘which kinds of monies do we use for which purposes?’ as there are different kinds of money which are used for different purposes. Here, I want to stress that ‘receivables’ are: money. And are, at the moment, mainly used for inter-company purchases. The quarterly balance sheets (below) of Alphabet (formerly Google) show that, as of September 2020, Accounts Receivable had a value of almost 35 billion dollar. Accounts receivable are privately issued money. They are backed by the law but not created by banks or governments. They are created when a buyer promises to pay and a seller accepts this promise, a promise which can be legally enforced. But it’s not the payment by the debtor which defines the moment of the sale. The actual sale is

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

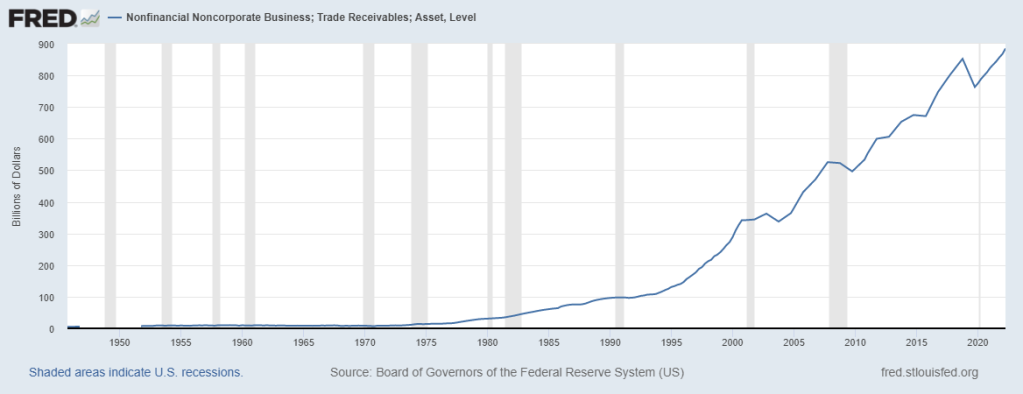

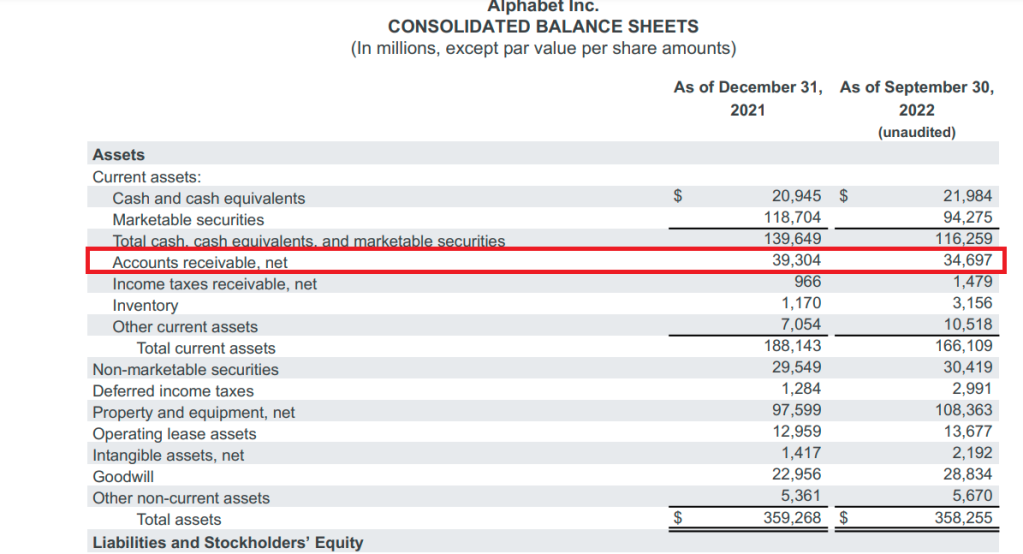

What’s money? Wrong question. The right question: ‘which kinds of monies do we use for which purposes?’ as there are different kinds of money which are used for different purposes. Here, I want to stress that ‘receivables’ are: money. And are, at the moment, mainly used for inter-company purchases. The quarterly balance sheets (below) of Alphabet (formerly Google) show that, as of September 2020, Accounts Receivable had a value of almost 35 billion dollar. Accounts receivable are privately issued money. They are backed by the law but not created by banks or governments. They are created when a buyer promises to pay and a seller accepts this promise, a promise which can be legally enforced. But it’s not the payment by the debtor which defines the moment of the sale. The actual sale is legally finalized when the seller accepts the promise of the buyer. That’s the moment when ownership changes hands. Receivables are stated in a unit of account, they are a legal means of exchange and they surely are a store of value (that’s why they are included on the balance sheet).

‘Accounts receivable’ and ‘Accounts payable’ (on the liability side of the balance sheet) are important. On every balance sheet of every company you will find a considerable amount of payables and receivables and, as there is a flow of them, the value of the quarterly flow might be quite a bit larger than the value on the quarterly balance sheet. It’s tempting to state that this idea of privately issued money is heterodox but it isn’t. It’s a common and universally accepted, albeit not neoclassical, idea. You will see them on every balance sheet but also in the macro statistics (graph below), notably the Flow of Funds. Fact: Marcus Goldman, the founder of Goldman Sachs, started his career in the 1870‘s by buying receivables (promises to pay by specified customers) owned by local craftsmen in New York at a discount and collecting the money. Anthropologists and historians state that there are different kinds of money, used in different spheres of life. At this moment in time, deposit money is used for groceries, rents and taxes while ‘payables/receivables’ are used between companies (even when credit card transactions, a spin off of the ‘payables/receivables’ system and the work of Goldman, do resemble the ‘payables/receivables’ system a little). Hundred dollar bills are used by criminals (the 500 Euro note, while still legal tender, is not issued anymore for comparable reasons). Money has many faces and a certain kind of money will be less of a universal means of payment than generally assumed. So, which monies are issued by which kinds of institution and used for what purpose? Think about this when reading stuff about Digital central bank currencies.