Financial wizardry recently caused massive problems for UK pension funds and the Bank of England. The Bank of England forces pension funds to take part in ‘LDI’ contracts which aim to insure possible future liquidity problems. These contracts however lead to real liquidity problems, which forced the Bank of England to intervene to prevent a market melt down. The solution became the problem. Deputy Governor John Cunliff of the Bank of England stated: “The Bank was informed by a number of LDI fund managers that, at the prevailing yields, multiple LDI funds were likely to fall into negative net asset value. As a result, it was likely that these funds would have to begin the process of winding up the following morning… In that eventuality, a large quantity of gilts, held as

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

Financial wizardry recently caused massive problems for UK pension funds and the Bank of England. The Bank of England forces pension funds to take part in ‘LDI’ contracts which aim to insure possible future liquidity problems. These contracts however lead to real liquidity problems, which forced the Bank of England to intervene to prevent a market melt down. The solution became the problem.

Deputy Governor John Cunliff of the Bank of England stated:

“The Bank was informed by a number of LDI fund managers that, at the prevailing yields, multiple LDI funds were likely to fall into negative net asset value. As a result, it was likely that these funds would have to begin the process of winding up the following morning… In that eventuality, a large quantity of gilts, held as collateral by banks that had lent to these LDI funds, was likely to be sold on the market, driving a potentially self-reinforcing spiral and threatening severe disruption of core funding markets and consequent widespread financial instability.”

Notice the ultra short periods whichm presumably, are specified in the LDI contracts: ‘Cash, Now!’. I haven’t read any of these contracts, if somebody can provide me with one: please! I do not see any reason for such ultra short periods.

This did not just happen in the UK. Related problems in the Netherlands in 2020 forced the ECB to intervene, to prevent a market melt down. This led Anil Kashyap, in a November 2020 speech at the Bank of England about the March 2020 crisis, to issue the next warning (emphasis added):

“One is whether the regulatory system addresses these challenges adequately? We do have some

protections in place that require liquidity buffers for some sectors. Are these sufficient? We can also ask

whether the post GFC regulatory reforms we have enacted might have inadvertently created incentives to organise funding through chains that are particularly vulnerable?”

The Bank of England was warned. They are to blame. They did not take immediate action to force pension funds to wind down the ‘LDI” contracts, which, as was shown in 2020, are the source of the fragility. It is worthwhile to investigate the situation in more detail. I will do this below, using data form De Nederlandsche Bank (Dutch Central Bank) about the consolidated Dutch pension fund sector.

To do this, we first have to answer some questions.

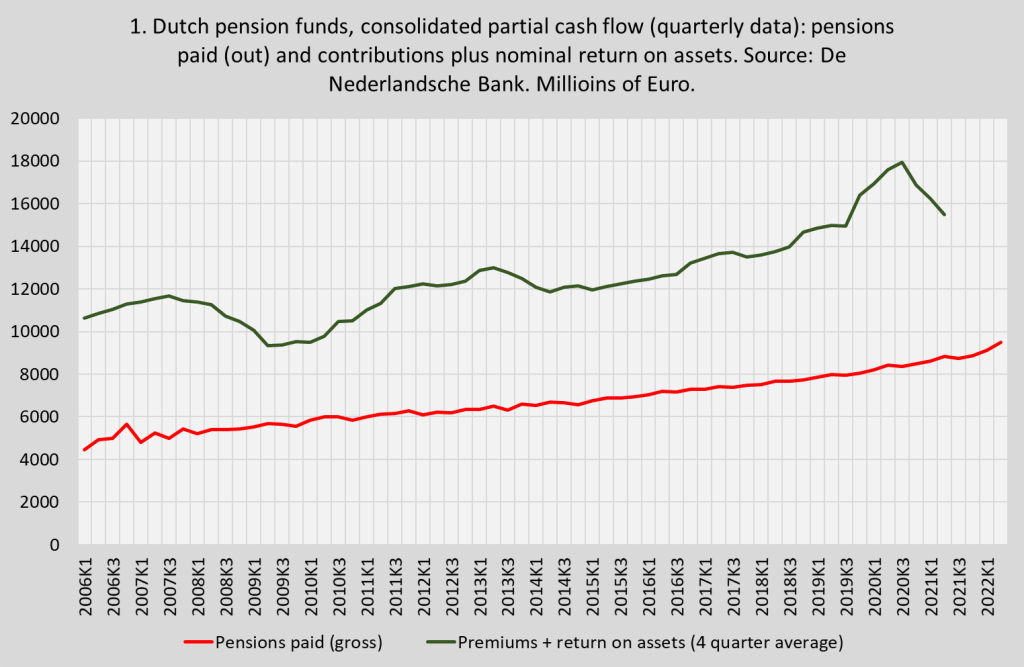

- The first: do Dutch pensions have a liquidity problem. The answer is: no. Looking at the ‘core business’ (graph 1) of funds for the last 16 years, we see an inflow of cash which is roughly twice the size of the outflow (pensions paid). Of course, some money goes to costs and the like, more on that below, but generally there was, ahem, no problem. It is important to know that this was not just caused by generally a quite high nominal return on investments but also by risk mitigating strategies: for ten years, Dutch pensions have not been indexed (they stayed the same in nominal terms). The pension age increased from 65 to 67. And premiums increased quite a bit (with about 9% of gross income of members of the funds). The collectivity is the risk bearing entity. Core cash outflows of pensions are extremely predictable (see the yearly report of the ABP, the largest Dutch pension fund)

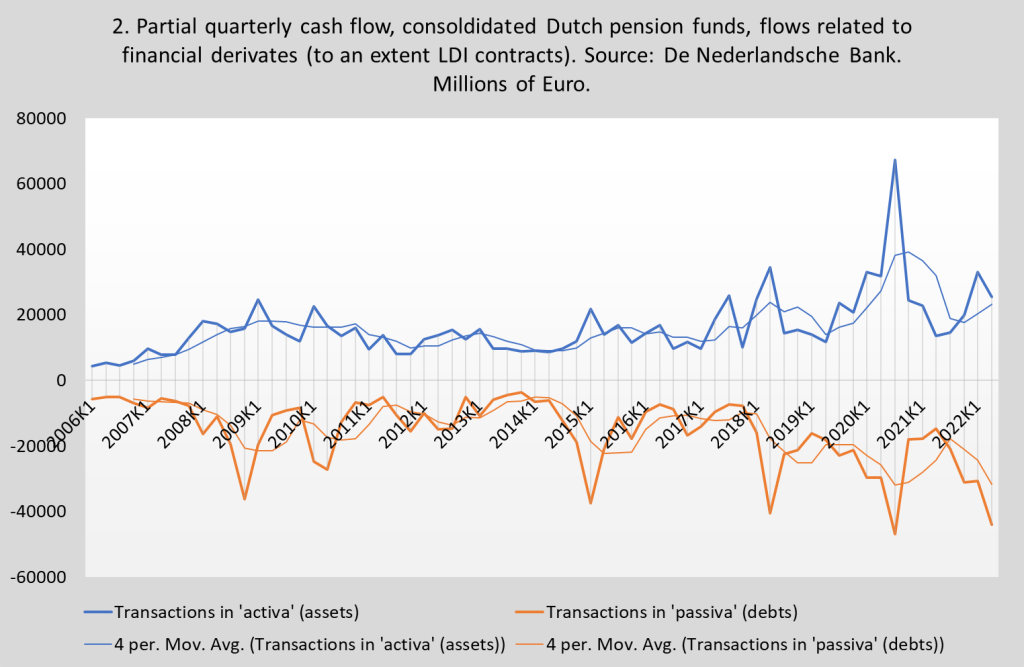

- The second question: if there were no liquidity problems (to the contrary, the question was where they had to stack the cash) why did pension funds have to invest in these LDI contracts? I did not read the contracts but it seems to that they are based on the assumed return on assets. The problem: liabilities (pensions to pay) have a duration of 19,5 years (data from the Yearly report of the ABP, the largest Dutch pension fund) while many assets (government bonds). Assets like government bonds often have a shorter duration, like five years. Which leads to the risk that when these bonds reach maturity and the money has to be reinvested the next part of the 19,5 period, the interest rate on bonds may differ from the rate of the matured bonds. If these bonds have a rate of 0% the new bonds might have a rate of -2%. Or +6%. If the present rate is 0%, the -2% will be a whammy for the funds as the LDI stipulate that in that case, the counterparty has to pay. While the +6% will be a boon for the counterparty (say: Goldman Sachs). If it’s -2% the funds will receive money, if it’s 6% they have to pay money. Eduard Bomhoff suggests that conterparts gambled that, in case of interest rates which are already negative, the chance of a large increase is larger than the chance of an equally large decrease, while funds were captive customers… The sums due are calculated on a daily basis (huh…?), assuming interest rates today are indicative for interest rates at the end of the duration period of the assets (it’s a bit more complicated than this as liabilities are discounted, too, but I do think this is the gist of the argument). Meaning that when rates suddenly rise from 0 to 1% (and they can rise suddenly) pensions funds directly (huh…?) have to pay huge amounts of money. Graph 2 is as close as I can get to these flows, for the Netherlands. These are quarterly data, not the daily flows which caused the fragility problems. Even then it is clear that after 2019 liquidity flows increase quite a bit, while they are much larger than the ‘core business flows.

To an extent, these flows are related to LDI contracts and the increase after 2019 surely seems entirely caused by these contracts (look here). But: do the funds need these contracts? No. If we extend the data 19,5 years, assume a steady flow of premiums, assume a gradual doubling of payments and half the flow of dividends while assuming that the predictability of pension payments enables a gradual sell off of assets – there is zero liquidity problem. Zero. The funds own 1,5 trillion. Even if this value is halved there still is no liquidity problem. There might be a funding problem for the longer term but that’s not the question here and if assets diminish in value that problem would not be solved by LTI contracts. Central Banks are to blame. And yes, the way assets and liabilities are discounted are deeply rooted in neoclassical economics. funds had to invest in these costly and fragility enhancing LDI contracts becaused they were forced by central banks, which could have known better (see above), but which chose to continue to use flawed economic analysis.

Addendum: the Dutch pension system has three pillars.

- A social democratic pillar, called AOW. This is a kind of not means tested basic income for everyone financed by taxes. Some intricacies to these taxes but it is based on the State and the Population.

- A Christian corporatist pillar. This is a non-state pension fund system financed by forced savings, mainly for wage workers. The state regulates these funds, but they are not part of the state.

- A classical liberal party, consisting of voluntary long term savings which are deductable from taxes (all pensions are taxed, however). this is quite regulated, too.

At this moment, Dutch neoliberal economists and politicians, inspired by neoclassical economics, are trying to dismantle the second pillar and to change the collective contract (an insurance) to individual savings accounts. Arguing with these people it turns out that they just can’t grasp the idea of a collectivity and try to understand everything within the framework of rational consumers and idealized general equilibrium markets. Even when it’s clear that, as premiums have increased and the pension age has gone up and there is a possibility that the central bank will force pension funds to decrease pensions, the collectivity is a risk bearing entity they continue to state that these are defined benefit pensions (this idea was abolished in 1996). Weird. Also, people are of no rational ‘homo economicus’. But the new law requires pension funds to act as if they are, as they have to measure ‘generational risk aversion’. No such thing exists, which makes measurement slightly difficult. Anyway: christian social thinking is replaced by neoliberal individualized contractual market thinking.