From C.P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh The monetary policies of the major advanced economies have been obsessively nationalist for more than two decades now, with hardly any genuine international cooperation beyond some coordination among G7 economies. These policies in turn have had all sorts of impacts—often very negative—in the rest of the world, and particularly in the low and middle income countries referred to collectively as emerging and developing economies (EMDEs). After the Global Financial Crisis, the advanced economies unleashed historically loose monetary policies, with major liquidity expansion and very low or even negative interest rates of their central banks. This enabled and encouraged massive increases in debt both within their own economies and in the rest of the

Topics:

Editor considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from C.P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

The monetary policies of the major advanced economies have been obsessively nationalist for more than two decades now, with hardly any genuine international cooperation beyond some coordination among G7 economies. These policies in turn have had all sorts of impacts—often very negative—in the rest of the world, and particularly in the low and middle income countries referred to collectively as emerging and developing economies (EMDEs).

After the Global Financial Crisis, the advanced economies unleashed historically loose monetary policies, with major liquidity expansion and very low or even negative interest rates of their central banks. This enabled and encouraged massive increases in debt both within their own economies and in the rest of the world, as banks and other financial companies sought to use cheap money to maximise returns in sectors and locations that would otherwise not record much capital inflow. Since these cross-border capital flows were inherently speculative, much of this debt was short-term in nature or in bond markets that facilitated easy withdrawal.

This rush of finance of emerging and “frontier” markets did not necessarily result in productive investment. Instead, they typically pushed up domestic assets prices and caused exchange rate appreciation in the recipient countries, which actually worked against encouraging more investment in tradeable sectors even as they made the balance of payments more fragile and vulnerable to sudden shocks.

The impact of this became starkly evident during the Covid-19 pandemic, when advanced economies once more engaged in massive liquidity expansion, accompanied this time by very large fiscal stimuli. By contrast, EMDE governments on average spent significantly less (in fiscal terms) than they had after the Global Financial Crisis, and their own monetary policies were affected by the need to manage the very volatile flows of global capital from 2020 onwards.

Then, as inflationary pressures created the knee-jerk reaction of tighter monetary policies and rising interest rates in the advanced economies, a new and different set of pressures has emerged, this time causing recession. EMDEs that have barely recovered from the pandemic and are already dealing with significant external debt overhangs, taken on by both public and private sectors, are being forced to respond to interest rate hikes in the US and EU, by forcing up their own rates.

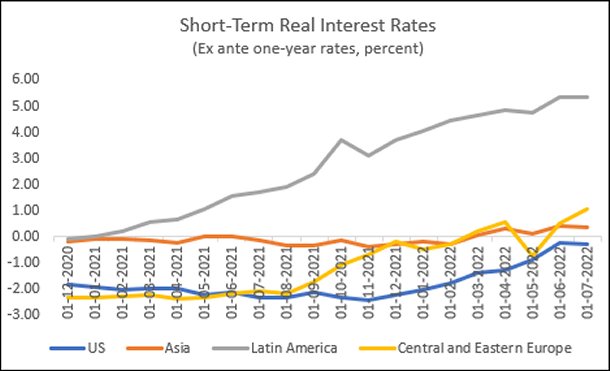

True to form, the EMDEs now have to impose even bigger increases in interest rates than the advanced economies, with even more adverse effects on domestic economic activity and employment. As a result, real interest rates have risen sharply in all developing regions. Figure 1 shows that, despite significant recent hikes, real short-term rates in the US remained negative until July 2022, although they have probably moved into positive territory since then. But real interest rates have turned positive in developing Asia (and would show even greater increases if China were excluded) and central and eastern Europe, and have risen to very high positive rate in Latin America.

Figure 1

Source: IMF Financial Stability Report Oct 2022

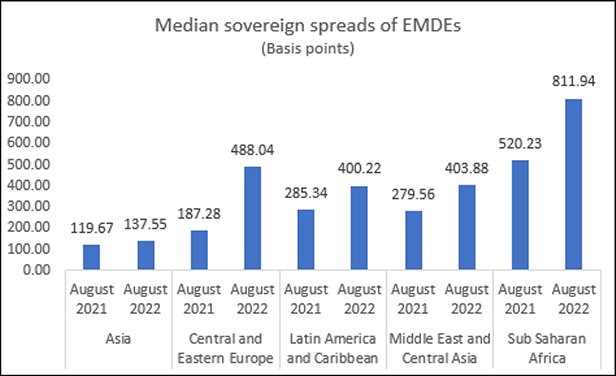

Despite their domestic macroeconomic policy efforts (or partly because of them, since it is evident that the outcome of higher interest rates and restrained fiscal stance will be recessionary) the bond markets have punished EMDEs as a result of policies implemented in advanced economies. Figure 2 shows that the median spreads on sovereign bonds have increased sharply over the year to August 2022, with truly dramatic and destructive increases in central and eastern Europe and sub-Saharan Africa. Once again, the situation is likely to have deteriorated further since then, making repayment even harder and more likely for many countries.

Figure 2

Source: IMF Financial Stability Report Oct 2022

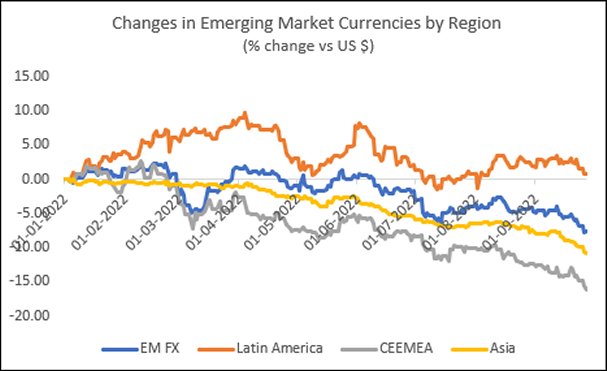

Despite higher interest rates (at some damage to domestic economies) and fiscal tightening, the bleeding of capital from EMDEs continues. This has generated significant nominal depreciation in most EMDE currencies. Figure 3 shows that the average EMDE index of currencies vis-à-vis the US dollar has shown significant decline throughout the year, and this has encompassed all regions other than Latin America. Of course, some debt-distressed countries have experienced truly large declines, in the range of 20-40 per cent since the start of the year.

Figure 3

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook October 2022

Exchange rate depreciation is usually seen to have contradictory effects: a positive effect on exports and tradeable goods (and thereby on domestic economic activity) and a negative effect on inflation and on imports of essential goods. In the current global scenario, the net positive export effect is likely to be extremely muted if not absent for most countries, as global trade continues to falter. Instead, the problem of rising costs of imports, and particularly food and fuel imports, will be worsened by the exchange rate devaluations that are adding to the impact of higher global prices.

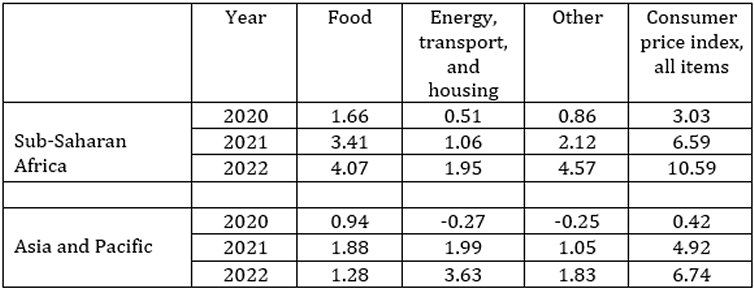

Indeed, as we have noted in an earlier MacroScan (https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/opinion/a-food-crisis-not-of-their-making/article65911286.ece) even as global food and fuel prices have gone through the speculative bubble and are now back to levels of the pre-Ukraine War period, prices in EMDE have continued to rise. Table 1 shows the increasing impact of food and energy on the total consumer price inflation in EMDEs of sub-Saharan Africa and Asia and the Pacific. In countries in which food items still constitute between one-third to one-half of the consumption basket, particularly among the bottom half of the population that is already poor, this is a serious problem. And because energy prices necessarily enter into production and distribution of all goods and services, energy-importing countries are also very badly affected.

Table 1: Inflation driven by food and fuel (annualized per cent)

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook October 2022

What makes it all so much worse is that most EMDEs—under the misleading advice of the IMF—are following the same hatchet approach to monetary policy as the advanced economies, of higher interest rates and fiscal consolidation. This is counterproductive, as it does not address the causes of inflation while adding to recessionary forces. Instead, more imaginative policies better tailored to specific needs are required: capital controls that prevent volatile movements of capital that add to depreciation; price management of essential commodities, especially those that have strong forward linkages; specific policies oriented to ensure greater supply of such goods; and fiscal policy focused on social protection for those affected by inflation and loss of livelihood.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on November 14, 2022)