From Dean Baker Last week, David Brooks had a column that was quite literally a celebration of American capitalism. He makes a number of points showing the U.S. doing better than other wealthy countries over the last three decades. While his numbers are not exactly wrong, they are somewhat misleading. (I see Paul Krugman beat me to the punch, so I’ll try not to be completely redundant.) Brooks points to the faster GDP growth in the United States than in other wealthy countries. As Krugman notes, much of this gap is due to the fact that they have older populations; the differences are much smaller if we look at GDP per working-age person. However, a big part of the story is also that they have opted to take much of the benefit of productivity growth in the form of more leisure time. In

Topics:

Dean Baker considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from Dean Baker

Last week, David Brooks had a column that was quite literally a celebration of American capitalism. He makes a number of points showing the U.S. doing better than other wealthy countries over the last three decades. While his numbers are not exactly wrong, they are somewhat misleading. (I see Paul Krugman beat me to the punch, so I’ll try not to be completely redundant.)

Brooks points to the faster GDP growth in the United States than in other wealthy countries. As Krugman notes, much of this gap is due to the fact that they have older populations; the differences are much smaller if we look at GDP per working-age person.

However, a big part of the story is also that they have opted to take much of the benefit of productivity growth in the form of more leisure time. In France, the length of the average work year was reduced by 9.1 percent between 1990 and 2021. In Germany, the decline was 13.8 percent. In Japan, average hours fell by 20.9 percent. In the United States, the length of the average work year fell by just 2.3 percent. On this score, there is not much to brag about here.

Brooks also cites data showing that the U.S. has seen more rapid productivity growth than other rich countries over the last three decades. This is true (austerity, which is more widely practiced in the EU than in the U.S., is a great way to kill growth), but it is worth mentioning some complicating factors in these comparisons.

For example, more than one-sixth of our GDP goes to health care. As Krugman points out, life expectancy in the United States has been stagnating and, in fact, declining for the poorer half of the population. That suggests that the share of our output that has gone into health care hasn’t done us too much good. (It’s true the decline might have been larger if not for the increased spending, but I’m not sure we want to brag much that our system is great because it slowed the decline in life expectancy.)

There are other things that get counted in GDP, and therefore productivity, that are of questionable value. For example, the money devoted to preventing school shootings (e.g. stronger doors, security alarms, school security guards, and grief counselors after the fact) all add to GDP and productivity growth. In a context where we have school shootings, these might be worthwhile expenditures, but most people would probably agree that we were better off in 1990 when we didn’t have to spend this money and school shootings were a rarity.

The other point about productivity growth is that we are still living in a slowdown world. In the years from 1947 to 1973, annual productivity growth averaged 2.8 percent. Since 1990 it has averaged 1.9 percent. That isn’t horrible, but it is markedly slower than the Golden Age growth. It is also worth noting that much of this growth was due to the Internet boom from 1995 to 2005 when growth averaged 3.0 percent annually. In the years before and after this period, productivity growth averaged just over 1.0 percent.

As Krugman points out, the benefits of the growth we have seen went disproportionately to those at the top. The median wage grew by 18.9 percent from 1990 to 2022, an average of just over 0.5 percent annually. It’s also worth noting that almost all of this growth took place in the tight labor markets of the late 1990s and from 2015 until the pandemic.

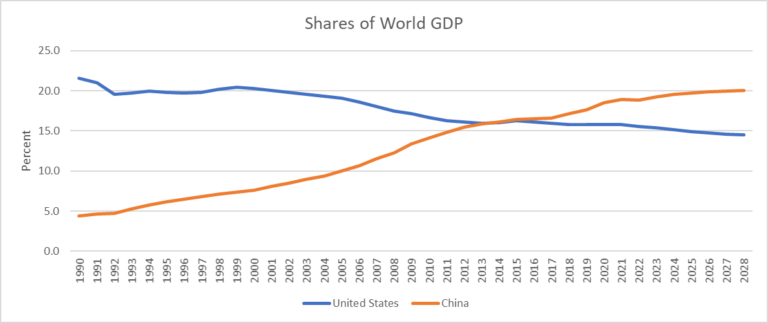

Finally, Brooks has the U.S. share of world GDP being unchanged in the years since 1990. This is likely because he was using GDP measured at exchange rate values. This is a rather arbitrary measure that varies hugely as currencies fluctuate. The U.S. GDP by this measure will also be inflated insofar as countries “manipulate” their currency by buying up dollar-based assets with their reserves.

A more standard measure of economic output for purposes of international comparisons is purchasing power parity GDP. This measure applies a common set of prices to all goods and services produced in each country. This measure tells a very different story.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

As can be seen, the U.S. share has declined from 21.5 percent in 1990 to a projected 15.4 percent this year. I have also included the I.M.F. projections which show a further decline to 14.5 percent by 2028. Perhaps more importantly, China’s share has risen dramatically.[1] It crossed the U.S. share in 2014 and is projected to be 19.3 percent this year. It is projected to rise further to 20.1 percent in 2028, not far below the U.S. share in 1990. In short, China is now the top dog in terms of contribution to work GDP by a fairly large margin.

There are still plenty of good things that can be said about the U.S. economy, but there is perhaps less to celebrate than David Brooks would have us believe.