No Christmas celebration on this blog this year. But a story about communities: the Commons of Buren and Hollum on the Waddensea island of Ameland. Commons have been studied by Elenor Ostrom. Studying Commons is of prime importance: we only have one earth. Reading Ostrom makes one optimistic. One of the things she mentions is the age of commons. Often, they survived centuries. Commons, which invariably voluntarily set limits on the use of resources, are sustainable. The Ameland Commons are no exception. They were also democratic and based on at least some measure of equality. Just like in other commons, on Ameland there were systems to appoint the managers. In Ballum, these were elected in a yearly election in a local pub, every head of a household had one vote. In Hollum there was a

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: accounting, common-poll-resources, commons, history, ostrom, scarce-resources, Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

No Christmas celebration on this blog this year. But a story about communities: the Commons of Buren and Hollum on the Waddensea island of Ameland. Commons have been studied by Elenor Ostrom. Studying Commons is of prime importance: we only have one earth. Reading Ostrom makes one optimistic. One of the things she mentions is the age of commons. Often, they survived centuries. Commons, which invariably voluntarily set limits on the use of resources, are sustainable. The Ameland Commons are no exception. They were also democratic and based on at least some measure of equality. Just like in other commons, on Ameland there were systems to appoint the managers. In Ballum, these were elected in a yearly election in a local pub, every head of a household had one vote. In Hollum there was a yearly mandatory rotation of a part of the management team. The yearly official change of seats took place in a local pub. Whenever there were two pubs in a village, there would be a rotation of pubs.

In 1896, a judge ordered the end of the Commons of Hollum (very long story), the Commons of Buren still exists. Even when the cowherd of Buren is, unlike one hundred years ago, not barefoot and does not sleep in a makeshift hut on the remote eastern part of the island anymore. Nowadays, he drives a quad. There are more nice stories. On this island, which used to be treeless, barren, and windswept, and as on other Waddensea islands, jawbones were used to delineate different parcels of land. Whale jaw bones, that is. We’ll return to this.

Ostrom provides us with eight rules for successful commons. Ostrom identified eight “design principles” of “Stable Local Common Pool Resource Management” (SL-CPRM)

“stable local common pool resource management:

1. Clearly defining the group boundaries (and effective exclusion of external un-entitled parties) and the contents of the common pool resource;

2. The appropriation and provision of common resources that are adapted to local conditions;

3. Collective-choice arrangements that allow most resource appropriators to participate in the decision-making process;

4. Effective monitoring by monitors who are part of or accountable to the appropriators;

5. A scale of graduated sanctions for resource appropriators who violate community rules;

6. Mechanisms of conflict resolution that are cheap and of easy access;

7. Self-determination of the community recognized by higher-level authorities; and

8. In the case of larger common-pool resources, organization in the form of multiple layers of nested enterprises, with small local CPRs at the base level.

These principles have since been slightly modified and expanded to include several additional variables believed to affect the success of self-organized governance systems, including effective communication, internal trust and reciprocity, and the nature of the resource system as a whole

Source: Wikipedia

I would like to add a ninth: meticulous administration.

One example from Ameland: in the twenties of the 18th century the Commons of Hollum paid fl. 1,50 for two large jawbones and 60 cents for a smaller one. Another one: even when more detail is generally not given, we do know how much all these elections in the local pub cost. An occasional mentining allows us to state that the money was spent on “pijpen en toeback” as well as on “jenever”. More generally: a key reason why we know the rules of the Commons and even that many survived the centuries: from an early age they had to write down detailed rules and keep detailed records, some of which ended up in archives.

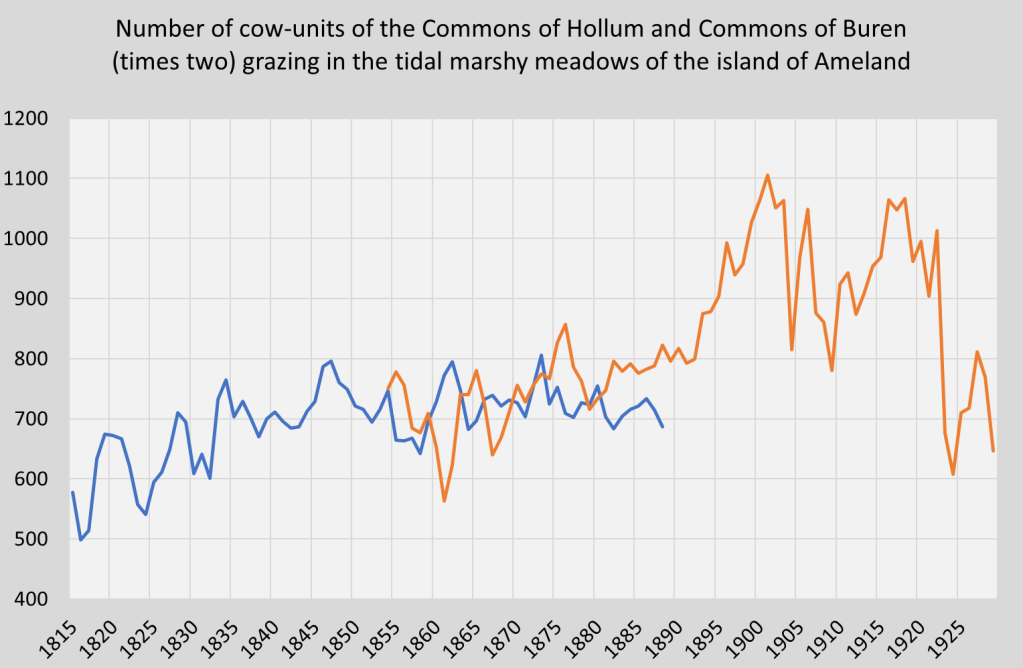

The graph below shows the number of cow units (consisting of cows, heifers, horses, and sheep) of the commons of Hollum and Ballum (yes, I do have to show I studied this in detail, you may forget this).

We can see the low level in 1816, the ‘year without a summer’ after the Tamborah Vulcano eruption of 1815. And the disaster of 1822 when over 120 cows drowned during a severe summer storm. Also, pub quiz question, when was artificial fertilizer introduced? But the point is that we have these data. And much more. Organizing the commons was, as there were over one hundred individual farms involved, no mean administrative task. Many monetary and non-monetary data had to be administrated (thank you, underpaid village teachers, for doing this). For each household, it was known how many cows were grazing on the tidal pastures. Reading Ostrom it turns out that this kind of very precise administrative, down to the individual tree in the Swiss mountains or down to the individual well for Californian Aquifiers, is necessary to make Commons work and to set voluntary limits on the use of the Commons. Limiting this, however, necessitates meticulous, precise, per household or per person accounting. On a planet with 8 billion people, sustainability and limiting the use of common resources require administration and arithmetic. Tracking and managing prices and invoking markets does not suffice. Tracking use will be necessary, too. To prevent an invasive government from doing this, we might have to take recourse to the lessons of the Commons.