Old charters still shed light on recent monetary developments… While in the Leeuwarden archive, investigating 19th century quantities and insurance prices of clay soil hay in central Friesland (a coastal part of the Netherlands) I got sub-focused and found myself thumbing through the Frisian ‘Charter books’ (internet version here). These books contain all Frisian government ‘oorkonden’ from the end of the fifteenth century onwards. ‘Oorkonden’ literally translates as ‘ear messages’. And they were: before Sunday mass or, later, sermon, they were read aloud in churches. These charters sometimes have a monetary nature. I happened to stumble upon some from 1579, the most revolutionary year in the entire history of Friesland (but see also this). Why and how did the new, revolutionary, and,

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

Old charters still shed light on recent monetary developments…

While in the Leeuwarden archive, investigating 19th century quantities and insurance prices of clay soil hay in central Friesland (a coastal part of the Netherlands) I got sub-focused and found myself thumbing through the Frisian ‘Charter books’ (internet version here). These books contain all Frisian government ‘oorkonden’ from the end of the fifteenth century onwards. ‘Oorkonden’ literally translates as ‘ear messages’. And they were: before Sunday mass or, later, sermon, they were read aloud in churches. These charters sometimes have a monetary nature. I happened to stumble upon some from 1579, the most revolutionary year in the entire history of Friesland (but see also this). Why and how did the new, revolutionary, and, more important, modern government get involved with monetary matters and why and how is this related to recent bank insolvencies?

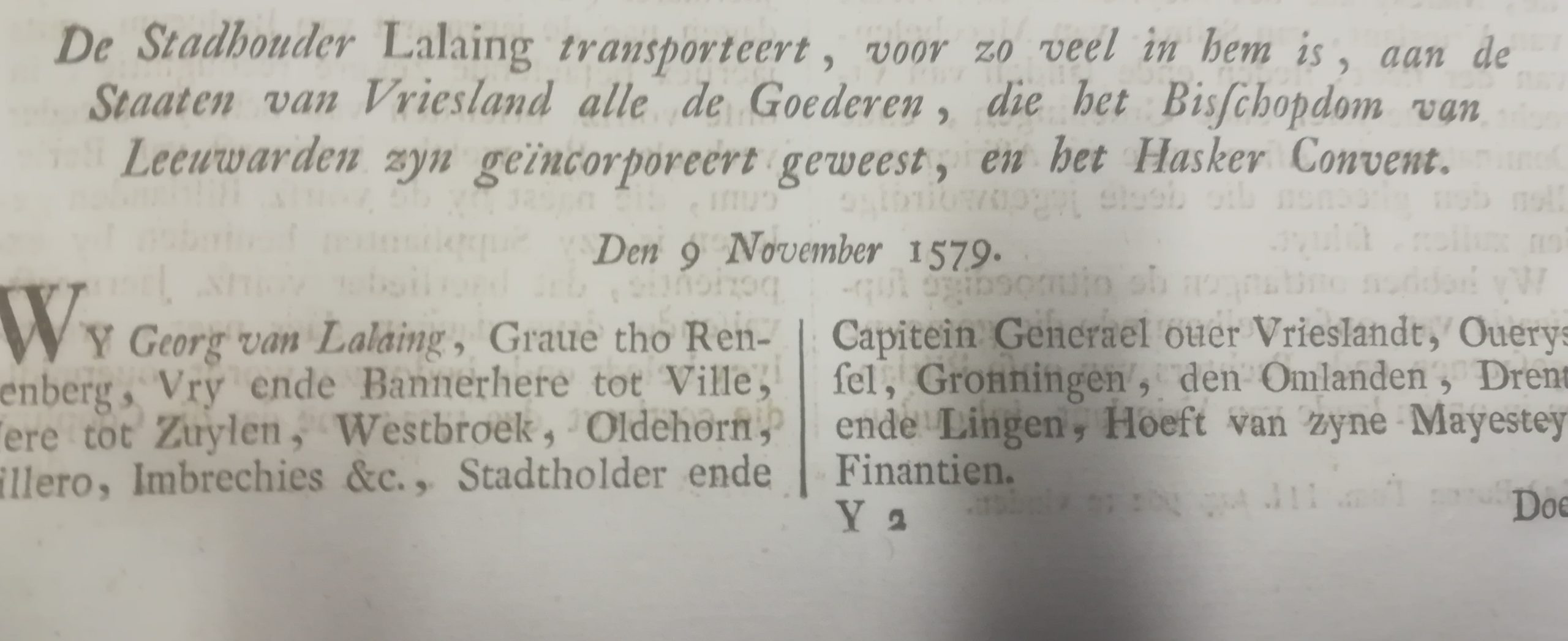

- Seizing, distribution and defining of ownership rights. The sizeable ecclesiastical lands from the monasteries and the bishopric (but not of the local churches) were seized which led to a large transfer of income (mainly land rents, look here for an interactive map of these lands) from the church to the state (exhibit 1, in Dutch (i.e. the language spoken in Holland), not in the local Frisian language, Translation is not important, the point is that the new, revolutionary government seized lands from the catholic church. Seizing ownership (or vesting it) is nothing new but is and was one of the crucial powers of the modern state, whoever controls this state. Mind: this was a ‘reasonable’ and I am tempted to say ‘Frisian’ revolution. The former monks got a pension while the former priests and their maids had to marry but could carry on (unless they chose to stay catholic, but the catholic church was not outlawed). Parts of the lands were re-distributed from the government to underfunded charitable institutions which took care of orphans and old widows while the rest was sold around 1635. Many of these institutions still exist.

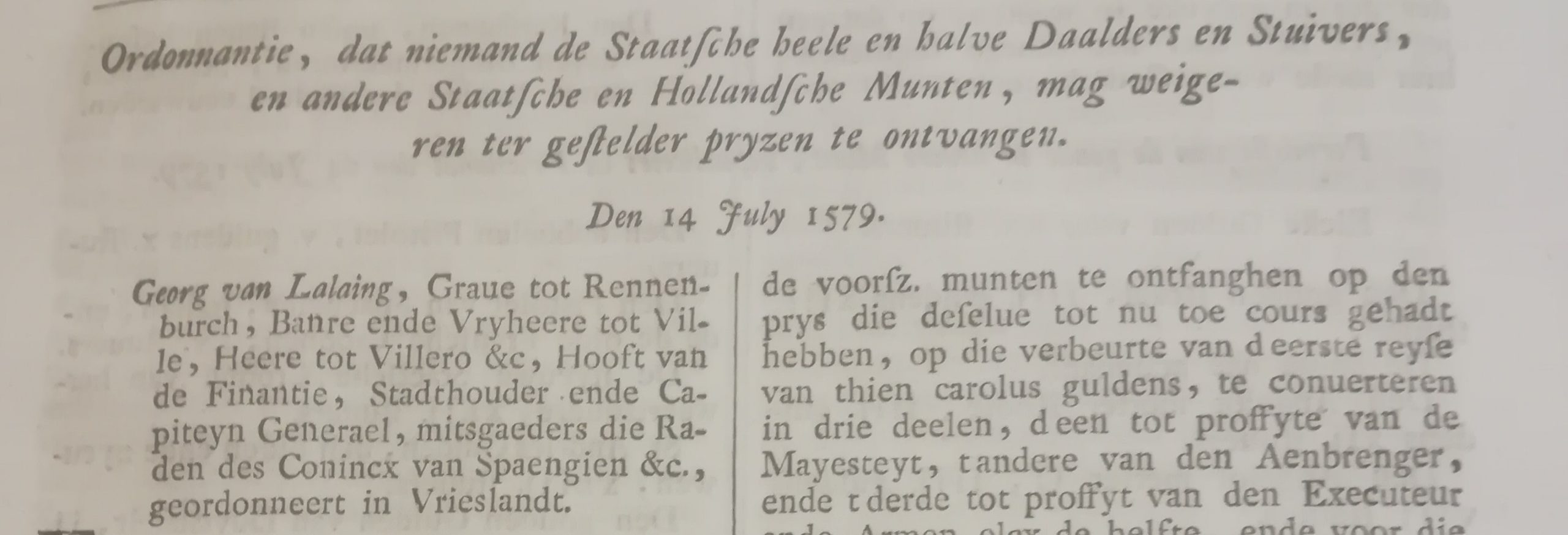

- People lost trust in the means of payment which forced the government to (try to) restore trust (exhibit 2 below). Here, translation matters. The exhibit explicitly denominates this means of payment as ‘Staatsche’ and ‘Hollandsche’ coins. Which relates to the dominant Dutch state at this moment, Holland. These were coins (‘Daalders’, ‘Stuivers’) emitted or at least guaranteed by the emergent Dutch state (The ‘Placcaat van Verlatinghe’, one of the inspirations for the USA ‘Declaration of independence’, was signed in 1581). Clearly, these were not accepted at par anymore and the ‘oorkonde’ states that not accepting them at par would be fined. Which had a meaning beyond direct payments with these coins. In those days there were, in Friesland, no banks. Also, most retail transactions were financed and paid by ‘payables’ – business to business or consumer to business debts which were often only paid after years. Looking at it from the side of the seller, the quality of these ‘receivables’ was important for the trust in his or her company of, stated otherwise, to his or her ability to issue his or her own ‘payables’. Guaranteeing the exchange value of the ‘coins of exchange’ (or trying to guarantee this) influenced the trust people had in the value of these ‘payables/receivables’, some of which were actually used as a means of payment. ‘Hey, I have to pay you twenty guilders, but mr A. have to pay me twenty guilders, so we’ll use his ‘payable’ as a means of paying my transaction’. In a sense, people were their own bank. Guaranteeing the value of debts (or trying to do this) has been a core function of modern governments for a long time. Aside: in those days, wife and husband both had to sign contracts as the property of women was required as collateral for these ‘payables’, too (Dutch women had their own property and, maybe more important, their own right to inheritances). Debts were collateralized, while the government strove to guarantee the unit of account of the state coins of exchange. Interestingly, but not surprising, taxes could not be paid using ‘payables’ but had to be paid using coins.

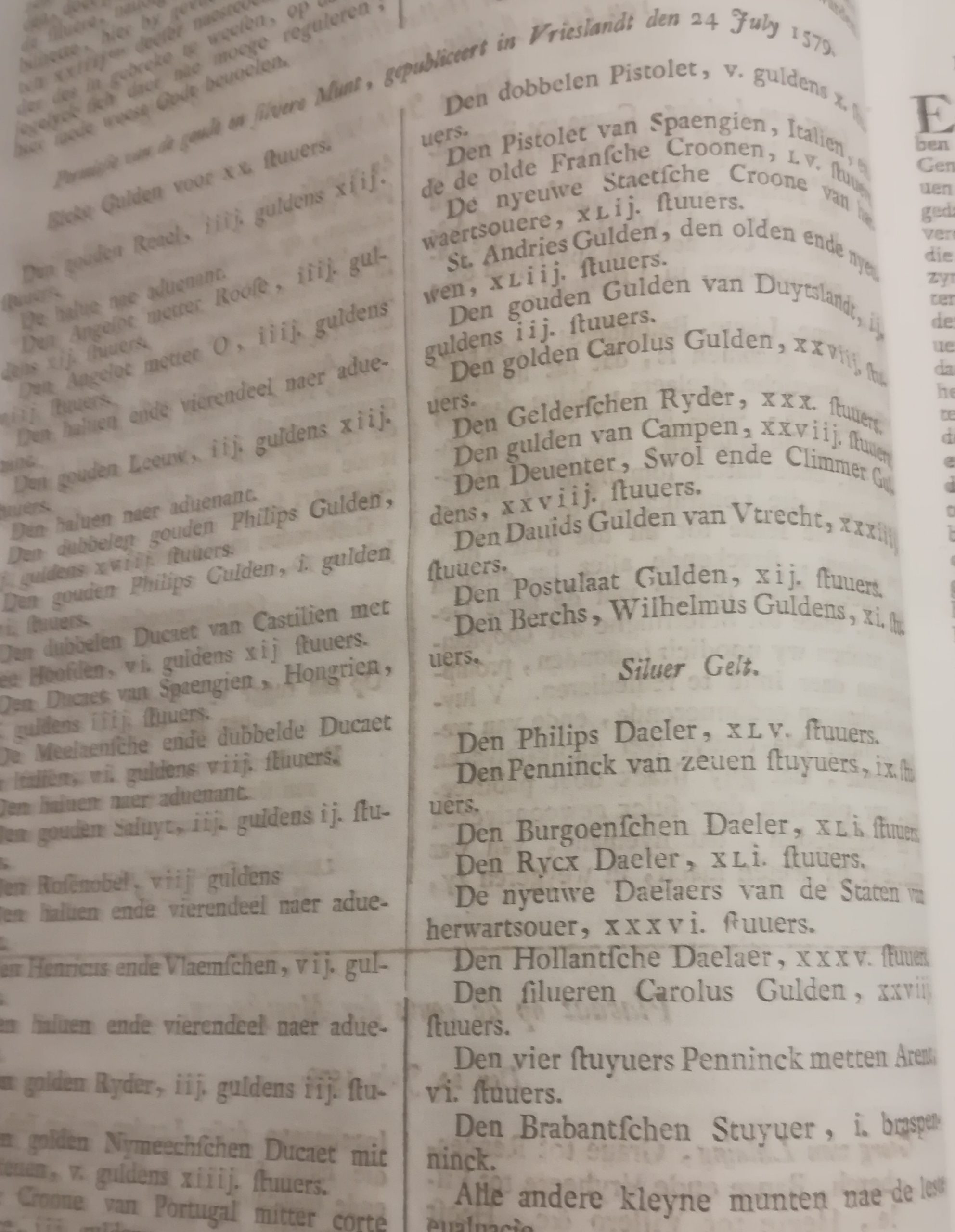

- The government tried to guarantee the exchange rate between different coins. In those days, a staggering number of coins were going around. The number of ‘bureaucratic’ units of account, i.e. the unit of account used in private as well as government written (tax)accounts, was to the contrary very limited (at this time Carolus Guilders of twenty ‘stuivers’, Carolus relating to Charles the fifth). In written contracts, accounts and charters, ‘The government unit of account always drives out other units of account’. As different coins were used as a means of payment this raised the problem of the exchange rate between bureaucratic money and the plethora of coins. The government solved this, or at least tried to solve this, by publishing official exchange rates (exhibit 3 below). Which were also used when accepting coins as a payment for taxes. This might seem not too relevant to the present. But it is. Nowadays, a lot of money creation is outsourced to banks. In a way, banks combine the role of the individual companies and people issuing and accepting payables and receivables and the government who coined money. When you think about it, deposit money is nothing else than a consumer’s or a companies ‘promise to pay’, i.e. a payable. When a consumer uses a credit card to buy a pair of hearing aids this means that he or she issues a ‘payable’ to a bank. The bank accepts this and transfers this promise (now called deposit money and denominated in the state unit of account) to the seller. Basically, this ‘deposit money’ is Credit Agricole or Deutsche Bank money as a specific bank accepts the ‘payable’ and transforms this into deposit money. There is no inherent reason why every bank should use the state unit of account (and indeed, USA and Japanese banks actually do use different units of accounts). Every system bank issues its own deposit money, but they all have a 1:1 exchange rate with cash (government money) and with the money of other banks, at least in the same monetary jurisdiction. Blunt example: there is no guaranteed A:B exchange rate between deposit money from a Japanese and a USA bank. But within a monetary jurisdiction, the government does guarantees the 1:1 exchange rate. In the sixteenth century, the government tried to ensure this by publishing official exchange rates (and accepted different coins as means of paying taxes using these rates). Nowadays, we call it ‘deposit insurance’. Guaranteeing exchange rates between different kinds of (deposit or coin) money is one of the key functions of modern governments. And has been for centuries.

- Defining, seizing and distributing ownership rights with an eye to income distribution but another to state finances, defining the unit of account, guaranteeing exchange rates and enforcing the acceptance of state money to promote the flow of money – it all sounds somewhat ‘Chartalist’. But how were these Frisian books called, again? ‘Charter books…’?

P.S.: the guy signing these charters, Georg van Lalaing, would in 1581 when the Plakkaat van Verlaatinghe was signed (which dissolved the Dutch bonds with the King of Spain) switch sides.