As nobody else bothers, I’m tinkering with designing a (badly needed) periodic table of prices. Look here and here. Economists are fond of ex post market prices – i.e. prices paid for actual transactions. But other kinds of prices abound. Administered prices, shadow prices, cost prices and more. Each of these prices are important and are used to influence the production and distribution of goods and services. Each of these are, separately, defined on all kind of webpages. but an intelligent overview and categorization is lacking. Hence this series. Today: insurance prices for hay and milk cows in Friesland, 19th century. What kind of prices were these? The answer: ‘commons-prices’, to introduce a neology. After 1810, Frisian farmers established mutual fire insurance companies.

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

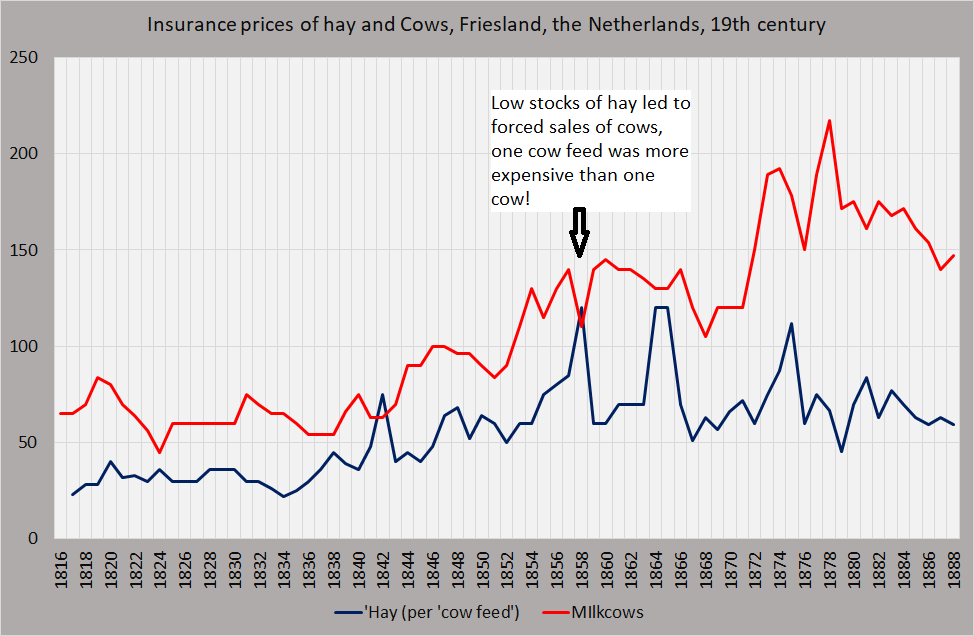

As nobody else bothers, I’m tinkering with designing a (badly needed) periodic table of prices. Look here and here. Economists are fond of ex post market prices – i.e. prices paid for actual transactions. But other kinds of prices abound. Administered prices, shadow prices, cost prices and more. Each of these prices are important and are used to influence the production and distribution of goods and services. Each of these are, separately, defined on all kind of webpages. but an intelligent overview and categorization is lacking. Hence this series. Today: insurance prices for hay and milk cows in Friesland, 19th century. What kind of prices were these? The answer: ‘commons-prices’, to introduce a neology.

After 1810, Frisian farmers established mutual fire insurance companies. Other members had to pay up when a farm of one of the members went down in flames. Individual risk was, on an ex post basis, mutualized. There were two main risks of fire: thunderstorms (during about the same time lightning rods were introduced) and the spontaneous combustion of hay (“hooibroei” in Dutch, “Hea broei in Frysian, a very common risk in areas with high quality hay, I could not find a matching English word). The risk was not new. Dutch farmers had used ‘hay rods’ (“hooiroede’, iron bars) to measure the internal temperature of hay stacks for centuries. But when ever more stacks of hay were stored in ever larger farm buildings instead of being stored separately in hay barns, the consequences of “hooibroei” increased (storing hay above the stables enabled large savings on labor). Membership of the mutual insurance companies spread like wildfire. To be able to pay the victims it was necessary to assess the value of lost hay (and cows and other stocks). These assessments were based on ex ante price lists. Every year in August, this list was, after due deliberation by the board, written down and farmers could extend their membership. How to judge these prices? Were these market prices? Nope. These were surely administered prices, as there was no individual of communal negotiation about these. They were inspired by market prices paid for hay (or cows, horses, wheat, clover and a whole bunch of other products) and hence were a kind of shadow price. They also clearly were administered prices, in the sense of Gardiner Means even when they were not based on cost prices but upon perceived market circumstances and prices. They also were a kind of ‘intra-organization’ prices, as the new mutual insurance companies can be understood as a kind of collective organization, a ‘Non Profit Serving Households’ in the parlance of the national accounts. Or a kind of ‘commons’ in the sense of Elinor Ostrom (her commons are, good to know, recognized by higher authorities, just like these mutual insurance companies). So, let’s call it a ‘commons price’: an administered price, expressed in a ‘unit of account’ per item and enforced by a governing body, which is used to exploit the ‘Blessings of the Commons’ as it regulates risk and redistributes and/or enables economic calculation and/or induces/enforces/enables behavior fostering the reaping of the Blessings. Prices should not just be categorized based upon technical aspects but also with regard to their institutional embedding! Think: fees of a union or a local soccer club. And the Univé insurance company, on of the heirs of the 19th century mutual companies, still is a non-profit cooperation charging a kind of commons prices. Aside: the combined value of cows and hay could, on diary farms, in 19th century Friesland easily be as high as the value of the impressive farm buildings (which I know as buildings were insured, too).