From Blair Fix When it comes to Bitcoin, there’s one thing that almost everyone agrees on: the network sucks up a tremendous amount of energy. But from there, disagreement is the rule. For critics, Bitcoin’s thirst for energy is self-evidently bad — the equivalent of pouring gasoline in a hole and setting it on fire. But for Bitcoin advocates, the network’s energy gluttony is the necessary price of having a secure digital currency. When judging Bitcoin’s energy demands, the advocates continue, keep in mind that mainstream finance is itself no model of efficiency. Here, I think the advocates have a point. If you want to argue that Bitcoin is an energy hog, you’ve got to do more than just point at its energy budget and say ‘bad’. You’ve got to show that this budget is worse than

Topics:

Editor considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from Blair Fix

When it comes to Bitcoin, there’s one thing that almost everyone agrees on: the network sucks up a tremendous amount of energy. But from there, disagreement is the rule.

For critics, Bitcoin’s thirst for energy is self-evidently bad — the equivalent of pouring gasoline in a hole and setting it on fire. But for Bitcoin advocates, the network’s energy gluttony is the necessary price of having a secure digital currency. When judging Bitcoin’s energy demands, the advocates continue, keep in mind that mainstream finance is itself no model of efficiency.

Here, I think the advocates have a point.

If you want to argue that Bitcoin is an energy hog, you’ve got to do more than just point at its energy budget and say ‘bad’. You’ve got to show that this budget is worse than mainstream finance.

On this comparison front, there seems to be a vacuum of good information. For their part, crypto promoters are happy to show that Bitcoin uses less energy than the global banking system. But this result is as unsurprising as it is meaningless. Compared to Bitcoin, global finance operates on a vastly larger scale. So of course it uses more energy.

To be meaningful, any comparison between Bitcoin and mainstream finance must account for the different scales of the two systems. So instead of looking at energy alone, we need to look at energy intensity — the energy per unit of circulating currency. That’s what I’ll do here. In this post, I compare the energy intensity of Bitcoin to the energy intensity of mainstream US finance.

Which system comes out on top? The results may surprise you.

Proof of energy wasted

Although many people know that the Bitcoin network uses lots of electricity, the reasons for this energy appetite remain widely misunderstood. So before we get to the energy data, it’s worth pausing for a brief primer on how the Bitcoin network works.

For starters, the Bitcoin network is nothing but a database — a monetary ledger that records transactions of digital currency. For their part, banks have a similar ledger that tracks how their customers spend money. With banks, however, the database is private and under their exclusive command. Not so with Bitcoin. Think of the Bitcoin database like the banking equivalent of Wikipedia. Anyone can read the ledger, and anyone can (in principle) write to it.

Admittedly, this latter part sounds crazy. If anyone can write to the Bitcoin ledger, it means fraud should be pervasive. (Why write a legitimate transaction when you can write a fraudulent one that benefits you?) And that’s precisely why write access to Bitcoin’s database comes with a caveat. To write transactions to the Bitcoin ledger, you must demonstrate that you’ve paid a toll. The purpose of this toll is simple: it makes writing to the ledger so expensive that fraud doesn’t payoff.

Now here’s the interesting part. On the Bitcoin network, the toll is computational. To gain write access to the database, Bitcoin users must demonstrate that they’ve solved a computationally intensive puzzle. Importantly, the only purpose of this puzzle is to prove to the community that you’ve wasted significant amounts of energy — so much energy that fraud becomes impractical.

Now in crypto circles, this approach is know as ‘proof-of-work’. To write a block of transactions to the blockchain (the ledger), you must prove that you’ve done the work needed to solve a taxing hash problem. But since the ‘work’ is done exclusively by electricity-guzzling machines, the system is more aptly described as ‘proof-of-energy-wasted’. It is a system purposefully designed to waste electricity.

Keeping numbers scarce

Looking at Bitcoin’s built-in waste, critics see enormous ‘inefficiency’. But I think that’s presumptuous. Built-in waste is not unique to cryptocurrency. It’s part of all financial systems.

To see this waste, it helps to think about the nature of ‘money’. In the most basic sense, money is just a mathematical idea. It’s a set of accounting rules attached to a system of property rights. Now, since numbers cost nothing to conjure, there’s no physical reason to waste energy on money ‘creation’. Anyone can conjure money, anytime they want.

And that’s precisely the problem. Numbers are infinitely plentiful. But money must be scarce. It is this (artificial) scarcity that converts numbers into ‘currency’. Without it, monetary accounting quickly devolves into the children’s game of number conjuring:

“I have a thousand dollars,” says Alice.

“I have a million dollars,” says Bob.

“I have a billion dollars,” says Charlotte.

And so on, to infinity.

Adults may laugh at this childhood naivety, but the joke is on us. Numbers can be conjured at will, exactly as the children understand. But what the children don’t understand are the (arbitrary) monetary rules that adults have internalized. To make numbers behave like money, we create rules about how monetary values can be conjured. Break these rules and you haven’t ‘created’ money. You’ve forged it.

It’s with ‘forgery’ that energy enters the picture. You see, it requires energy to ensure that monetary numbers are not conjured freely.

Paper cash is a good example of this principle. In essence, cash is a number delivery mechanism — a way to give monetary numbers a physical form. Since it is the numbers (not the paper) that matter, the design of a cash bill could be utterly simple — nothing but a digit scrawled on a plain piece of paper. Yet despite this modest requirement, actual cash has an elaborate design. Why?

The purpose of cash’s intricate design is to waste energy. By giving cash a complicated look, governments enforce monetary scarcity by making number conjuring expensive. If counterfeiters want to print money, they have to waste energy copying the government’s design. Sure, a few counterfeiters will take the challenge. But for most people, the cost of mimicking government cash isn’t worth the payoff.

And let’s not forget the cost of getting caught. To maintain their monopoly over money creation, governments actively prosecute and punish ‘illegitimate’ number conjurers. Like Bitcoin’s proof-of-work mechanism, this penal system is nothing but designed-in waste. Its purpose is to maintain monetary scarcity by upping the cost of fraud.1

Turning from paper cash to currencies based on precious metal, the built-in waste is even more severe. To conjure metal-based money, we’re forced to rip rare elements from the Earth’s bowels. With gold, that means wasting about 1.5 megajoules of energy to conjure a single US dollar.2 It’s the antithesis of efficiency. And that’s the point. Gold is a universal currency precisely because it’s scarcity provides a way to reign in number conjuring. If there were some highly efficient method for creating gold — say alchemy — it would ruin gold’s monetary appeal.

With Bitcoin, the situation is similar. Bitcoin’s creator, the pseudonymous ‘Satoshi Nakamoto’, realized that money is simply an accounting ledger that keeps numbers scarce by enforcing a set of rules. How are the rules enforce? By wasting energy.

Looking at the prospect of a digital currency, Satoshi decided that it made sense for the scarcity-inducing waste to be computational. Hence we get Bitcoin’s use of ‘proof-of-work’ — a purposefully wasteful algorithm that is designed solely to enforce the rules of the monetary ledger.3

So does Bitcoin waste loads of energy? Absolutely. But so do all monetary systems. The important question, then, is whether Bitcoin’s waste budget is worse than other forms of currency. And that remains an open question.

Bitcoin’s energy appetite

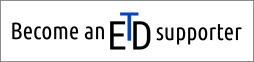

Lifting the hood of the Bitcoin network, let’s now look at its energy demands. Figure 1 shows one of the more rigorous estimates of Bitcoin’s evolving energy budget.

The data comes from the Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index (CBECI), and works as follows. The CBECI first looks at the Bitcoin ‘hash rate’ — the rate that Bitcoin miners guess solutions to their proof-of-work puzzles. Next, the CBECI looks at the technology used for hashing and estimates its ‘efficiency’ — the hash output per unit of electricity input. Finally, the CBECI divides the hash rate by the hashing efficiency, giving an estimate for Bitcoin’s electricity budget.

In this calculation, the main unknown is the mix of hashing technology used by miners. The CBECI knows which technology is available (on the market), but not what’s actually employed. Hence there’s significant uncertainty in their energy estimate.

Fortunately, the growth of Bitcoin’s energy budget has been so spectacular that the surrounding uncertainty is relegated to background noise. Figure 1 shows the pattern. Over the last fourteen years, Bitcoin’s energy thirst has grown by a factor of a million. (The shaded region shows the uncertainty in this estimate.)

As of early 2024, Bitcoin’s energy budget stands at roughly one million Terajoules. No doubt this number sounds large. However, energy units are notorious for being unintuitive. So before we continue, it’s helpful to place Bitcoin’s energy consumption on a more understandable scale.

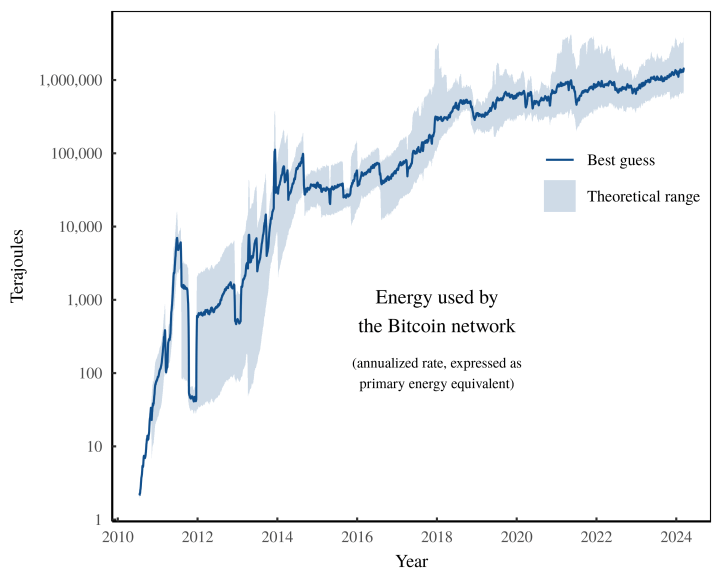

For their part, journalists like to point out that Bitcoin uses more energy than ‘entire countries’. It’s an apt comparison. Figure 2 show’s Bitcoins energy budget on the scale of various countries. When the Bitcoin network first got rolling, it used as much energy as the tiny island nation of Kiribati (population: 100,000). But today, Bitcoin uses as much energy as Sri Lanka (population: 20 million).

Endemic waste in mainstream finance

Now that we’ve estimated Bitcoin’s energy appetite, it’s time to do the same for its primary alternative — namely, mainstream finance. Here, things get more difficult.

The sticking point has to do with what system scientists call ‘boundaries’. To measure the energy used by a system, you’ve got to first define the boundaries where the system begins and ends. The more expansive your boundaries, the more energy you’ll end up counting.

Looking at the mainstream financial system, it’s not clear how we should define our energy boundaries. A tempting option is to simply reuse our Bitcoin method and sum the electricity use by banking computers. But I think this approach is a bad idea, because it misunderstands the difference between the two systems.

When you walk into a Bitcoin mining operation, you see nothing but energy-burning computers. But when you walk into a traditional bank, you see much more than that. Sure there are computers. But there’s also a brick-and-mortar office building. And most importantly, the bank is full of people. Collectively, the finance industry employees millions of people who are generally well paid. It’s here that we find mainstream finance’s primary form of waste.

![]()

Now that I’ve insulted everyone who works in finance, let me back up a bit. We’re not accustomed to treating people’s income as a form of ‘waste’. So let me make the connection.

Think of Bitcoin as a technology for automating monetary transactions. Instead of having a bureaucracy that manages the monetary ledger, Bitcoin lets computers do the job. As we’ve seen, this automation leads to the profligate use of electricity — energy which most of us would agree is ‘waste’. But if Bitcoin ‘wastes’ energy on automating transactions, it follows that mainstream finance ‘wastes’ energy on non-automation. It pays people to do a job that (conceivably) doesn’t need to be done.

So which system is more wasteful. Is it Bitcoin, with its thirst for computation? Or is it mainstream finance, with its reliance on millions of well-paid people?

For his part, Bitcoin’s creator thought that the answer was clear. In a 2009 email, Satoshi argued that Bitcoin would be an ‘order of magnitude’ more efficient than mainstream banking:

If [Bitcoin] did grow to consume significant energy, I think it would still be less wasteful than the labour and resource intensive conventional banking activity it would replace. The cost would be an order of magnitude less than the billions in banking fees that pay for all those brick and mortar buildings, skyscrapers and junk mail credit card offers.

Was Satoshi correct?

The energy budget of US finance

To judge Satoshi’s claims, we need to measure the energy budget of mainstream finance. Here’s how I’ll do it.

First, I’m going to focus on the US financial system. Second, I’ll assume that the energy used by this system stems from the lifestyles of the people it employs. Third, I’ll assume that people’s energy consumption is a function of their income.

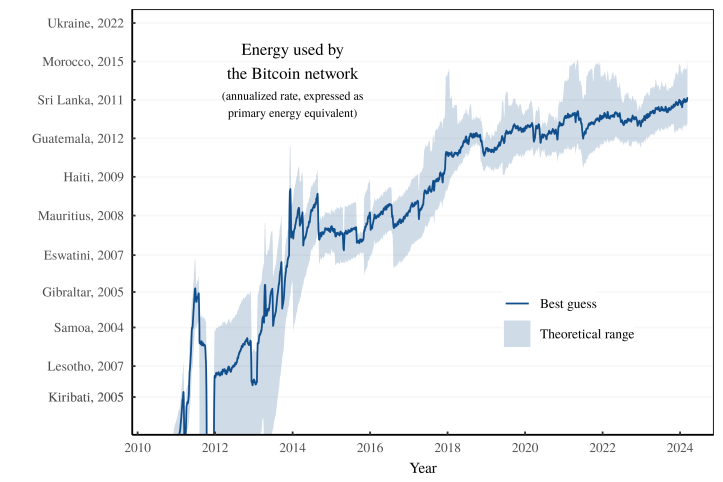

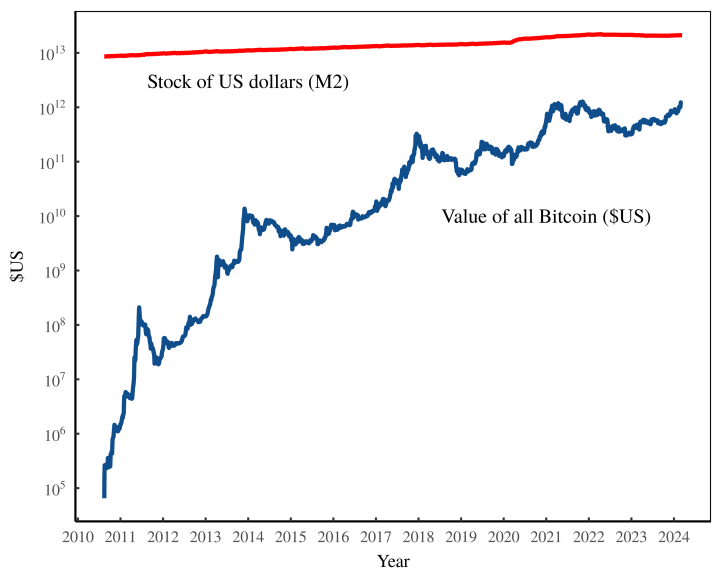

Starting with income, we know that US financial corporations receive about 6% of total American earnings. Assuming this income gets spent on energy, it follows that US finance sucks up about 6% the US energy budget. That equates to about 7 million Terajoules of energy per year. Unsurprisingly, that’s far more energy than is consumed by the Bitcoin network. Figure 3 shows the comparison since 2010.

Disparate monetary magnitudes

If I was writing a Bitcoin puff piece, I’d stop here and proclaim Bitcoin’s great ‘efficiency’. But hopefully, you see why this proclamation is premature.

The problem is one of scale.

Mainstream US finance operates on a vastly larger scale than the Bitcoin network. So it’s unfair to directly compare the energy budgets of the two systems. To make a fair comparison, we’ve got to put Bitcoin and mainstream finance on the same footing, which means accounting for their different scales.

How should we do that? Well, since we’re talking about two different monetary systems, the obvious approach is to sum monetary value. In the case of the Bitcoin network, there are about 19.6 million bitcoins, each priced at roughly $68,000 USD. That pegs Bitcoins’ market value at roughly $1.3 trillion USD.

Turning to US finance, the monetary calculation is more complicated, largely because there are many different types of financial instruments. For example, if we take Bitcoin to be ‘just another asset’, then it makes sense to compare its value to the sea of US corporate assets. Looking only at US public corporations, that sea is valued at roughly $50 trillion USD.

Alternatively, we can treat Bitcoin as a ‘cash asset’. In this case, it makes sense to compare its value to the stock of US cash, most commonly measured in terms of the ‘M2’ stock of money. In what follows, I’ll take this latter approach. The idea (which many people will contest) is that Bitcoin aspires to be a universal currency.4

Using the M2 stock of dollars to measure the scale of US finance, Figure 4 shows the degree to which the mainstream financial system dwarfs the Bitcoin network. In 2010, the chasm was enormous — roughly seven orders of magnitude. And even after a decade of explosive growth, the Bitcoin network remains valued at roughly 20 times less than the M2 stock of US dollars.

The energy intensity of Bitcoin relative to US finance

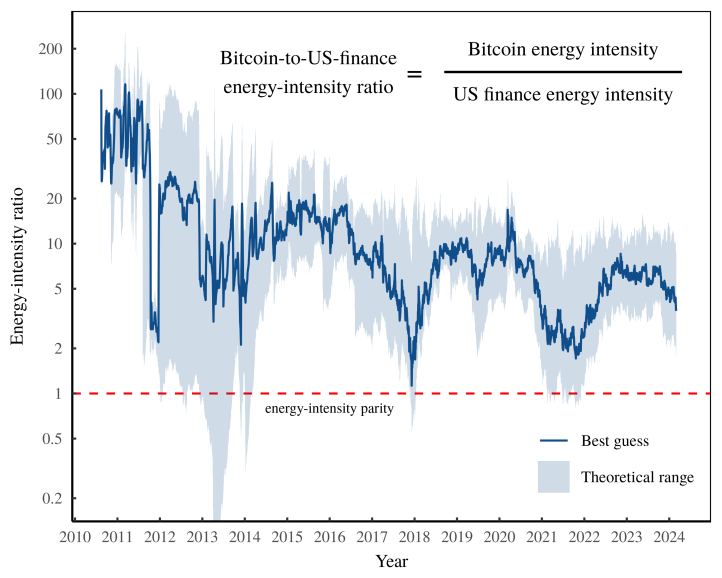

Now that we’ve measured both energy and monetary value, it’s time to combine the two measurements. Our goal is to create a fair way to contrast Bitcoin’s energy appetite with that of mainstream US finance. Our vehicle for this comparison will be the energy intensity of each system — the energy consumed per unit of circulating currency.5

To calculate Bitcoin’s energy intensity, we take its energy budget and divide by its market value (measured in US dollars):

Likewise, for US finance, we take the energy consumed by US finance (the energy required to support the lifestyles of everyone who works in finance) and divide by the M2 stock of US dollars. The result is the energy intensity of mainstream finance:

The caveat is that when viewed in isolation, these energy-intensity estimates are useless. That’s because monetary value is only meaningful as a point of comparison. So the final step of our analysis will be to compare Bitcoin’s energy intensity to that of US finance:

Plugging the data into our energy-intensity ratio gives the pattern shown in Figure 5. Immediately, we can dismiss Satoshi’s claim that Bitcoin is an ‘order of magnitude’ more efficient than mainstream finance. If anything, the opposite is true. Since 2010, the Bitcoin network has, on average, been about 13 times more energy intensive than mainstream US finance.

Looking closely at Figure 5, we see that Bitcoin’s worst period of waste was early on. In 2010 — long before anyone complained that Bitcoin was wasting loads of energy — the network sucked up about 50 times the energy of mainstream finance (dollar for dollar). To put that number in context, if Bitcoin had been scaled up to replace the circulation of US dollars, the Bitcoin network would have use about 3 times more energy than the entire US population.6 Outrageous.

Energy parity … and beyond?

In Figure 5, the main story is that compared to US finance, Bitcoin has historically been significantly more energy intensive. But looking closely at the evidence, there’s a subplot that we shouldn’t ignore.

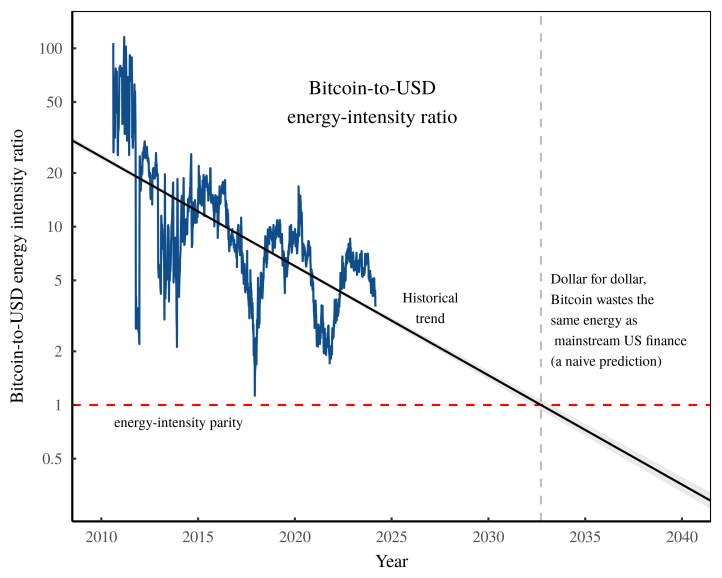

Over the last decade, it seems that the Bitcoin network has steadily closed the energy gap with US finance. Instead of being 50 times more energy intensive (as it was in 2010), today, Bitcoin is about 4 times more energy intensive. That’s a tenfold improvement. Intriguingly, if we project this improvement into the future, we find that Bitcoin may soon reach energy-intensity parity with US finance.

Figure 6 runs the numbers. A naive guess suggests that energy-intensity parity will arrive in the early 2030s. And if the trend continued, Bitcoin would then start to burn less energy (dollar for dollar) than US finance.7 Will this parity actually happen? Only time will tell.

Proof-of-stake: a less wasteful method for network consensus

They say that Bitcoin is ‘digital gold’. But unlike actual gold mining, there’s no physical reason that Bitcoin ‘miners’ must burn energy ‘harvesting’ bitcoins. The coins themselves are conjured numbers, and the ‘mining’ process is simply a software algorithm. And algorithms can be changed.

To recap, the function of Bitcoin ‘mining’ is to police the monetary ledger. Because Bitcoin has no governing institution, anyone is free to validate a transaction and write it to the ‘blockchain’. But that freedom also means anyone can commit fraud. The purpose of ‘mining’ is to stop fraud by making it so expensive that it’s impractical. To confirm a set of transactions, miners must demonstrate that they’ve wasted energy on a pointless computation. The reward for this ‘proof-of-work’ is a small amount of bitcoin.

As we’ve seen, the proof-of-work algorithm is no model of efficiency. It achieves consensus by wasting loads of energy. And that’s got cryptocurrency designers looking for different consensus-generating algorithms.

A promising alternative is a design called ‘proof-of-stake’. Here’s how it works.

Instead of letting users compete to validate transactions, the proof-of-stake algorithm uses a lottery. When it’s time to validate a ‘block’, a user is chosen at random from a pool of validators. The catch is that to get into this validator pool, you must put up a certain amount of currency as a ‘stake’. Like Bitcoin’s wasted computation, the purpose of this stake is to stop fraud. If a user ‘validates’ a fraudulent transaction, they risk losing their stake.

Because proof-of-stake (largely) does away with pointless calculations, it’s a more energy efficient design. Or at least, that’s the expectation.

The energy intensity of Ethereum

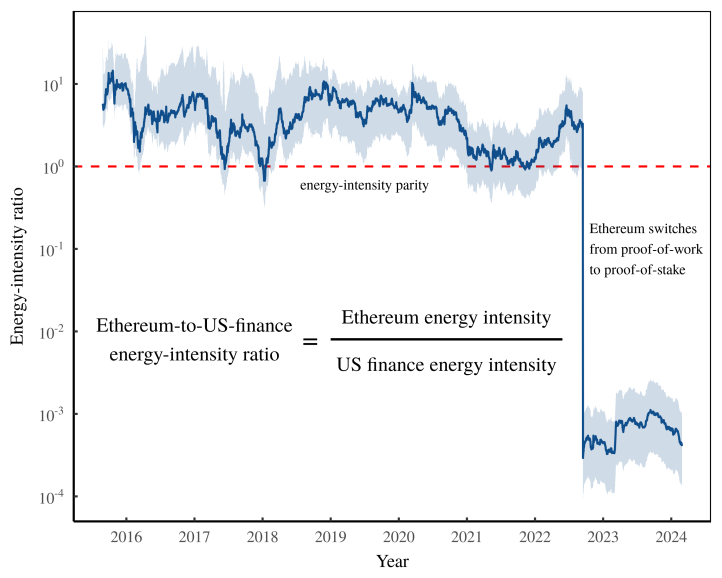

To measure the energy intensity of the proof-of-stake algorithm, we’ll look at Ethereum, the second largest cryptocurrency.

Created in 2015, the Ethereum network ran for almost a decade on the proof-of-work algorithm. During that time, its energy intensity was similar to Bitcoin. Figure 7 shows the data. From late 2015 to mid 2022, Ethereum was on average about 4 times more energy intensive than mainstream US finance.

Then something dramatic happened. On September 15, 2022, Ethereum switched its codebase to the proof-of-stake algorithm. (In crypto circles, the event is known as ‘The Merge’.) The result was a colossal drop in energy intensity. In Figure 7, the transition is easy to spot. Over the course of a day, Ethereum’s energy intensity plummeted by four orders of magnitude. So in terms of reducing crypto’s energy demands, the proof-of-stake algorithm seems like a no brainer.

Just the facts

Looking at the evidence in Figures 5 and 7, we can conclude two things about crypto.

First, coins like Bitcoin, which are based on the proof-of-work algorithm, are likely more energy intensive than mainstream finance. (But note that this intensity seems to be declining with time.) Second, coins like Ethereum, which are based on the proof-of-stake algorithm, are likely (far) less energy intensive than mainstream finance.

So that’s what the data says. But somehow, I feel like this evidence will satisfy neither the crypto critics nor the crypto advocates. And that’s why in the appendix, I add some obligatory speculation. But for now, let’s conclude with just the facts. To date, it seems clear that Satoshi’s claims about Bitcoin’s superior ‘efficiency’ have not come to fruition.