There is no ‘tragedy of the Commons.’ But a tragedy of the absence of Commons-as organizations, let’s call it ‘the tragedy of uncommons’, does exist. Below, I will provide the example of the island of Ameland in the Northern Netherlands, in line with the historical examples of successful Commons mentioned by Elinor Ostrom (especially those for Switzerland). Ownership is a multi-dimensional concept. Up to the 1795 revolution, the island of Ameland, north of Friesland, was not a part of the Dutch Republic, and ownership relations were somewhat archaic. The best way to understand this is to consider ownership a bundle of rights. In old Dutch deeds, some of these rights were described as “eer en feer, macht en gewalt,” loosely meaning: “political and juridical rights, the rights to

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: agriculture, ameland, commons, conservation, history, ownership, revolution, Sustainability, Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

There is no ‘tragedy of the Commons.’ But a tragedy of the absence of Commons-as organizations, let’s call it ‘the tragedy of uncommons’, does exist. Below, I will provide the example of the island of Ameland in the Northern Netherlands, in line with the historical examples of successful Commons mentioned by Elinor Ostrom (especially those for Switzerland).

Ownership is a multi-dimensional concept. Up to the 1795 revolution, the island of Ameland, north of Friesland, was not a part of the Dutch Republic, and ownership relations were somewhat archaic. The best way to understand this is to consider ownership a bundle of rights. In old Dutch deeds, some of these rights were described as “eer en feer, macht en gewalt,” loosely meaning: “political and juridical rights, the rights to sell, rent out and mortgage the land and the right to grow whatever you want”. Since 1704, the wealthy Oranje Nassau family owned the island of Ameland’s higher-level political and juridical rights and the right to rent out the rabbit. They also had the right to rent out lands. But this right was not tied to their ownership of the political and juridical rights but to their additional ownership of a kind of shares in the commons, the ‘achtendelen.’ They do not seem to have had any right to rent out the dunes, the coastal shallows, or, as they were called on the island, ‘Grie’. The rights to rent out these lands were simply not defined.

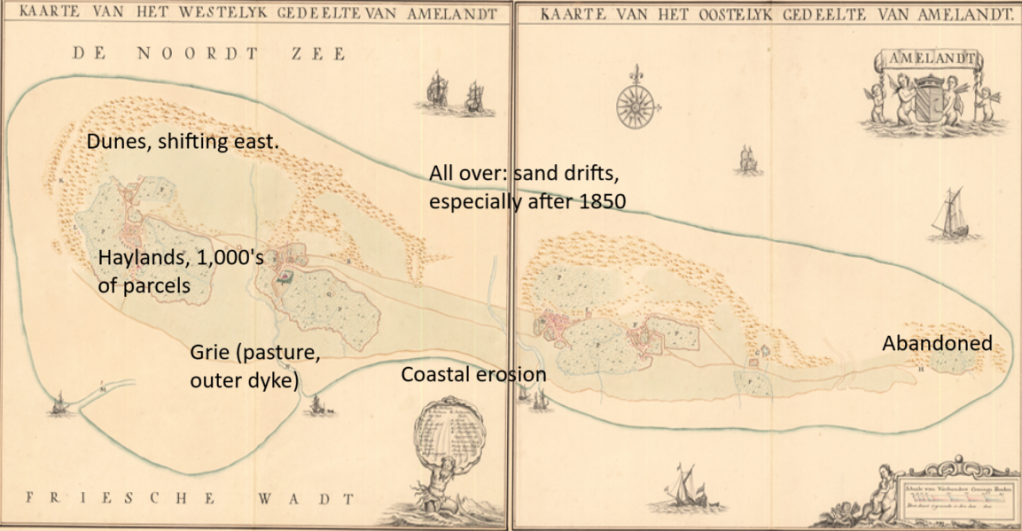

After the 1795 revolution in the Netherlands, higher-level juridical and political rights were uncoupled from land ownership. The Dutch also did what the English still have to do: almost all of the lands of the (after the restoration of 1815: royal) Oranje Nassau family were seized. On top of this, the island became part of the new Kingdom of the Netherlands. Nobody was very interested in the rabbits, the shifting dunes, the meager hay lands, and the eroding coastal marshes or, as they were called on Ameland, ‘Grieën’ — nobody, except for the many and small Ameland farmers and the caretakers of the commons. There were two relatively pure commons on the island, a hybrid one and a privatized one. Each of these had communally used pastures. And, from somewhere in September till the first of December, when all harvests had been gathered, the entire island transformed into one large communal pasture. Every horse, cow, and sheep were allowed to graze anywhere, including the ever-shifting dunes.

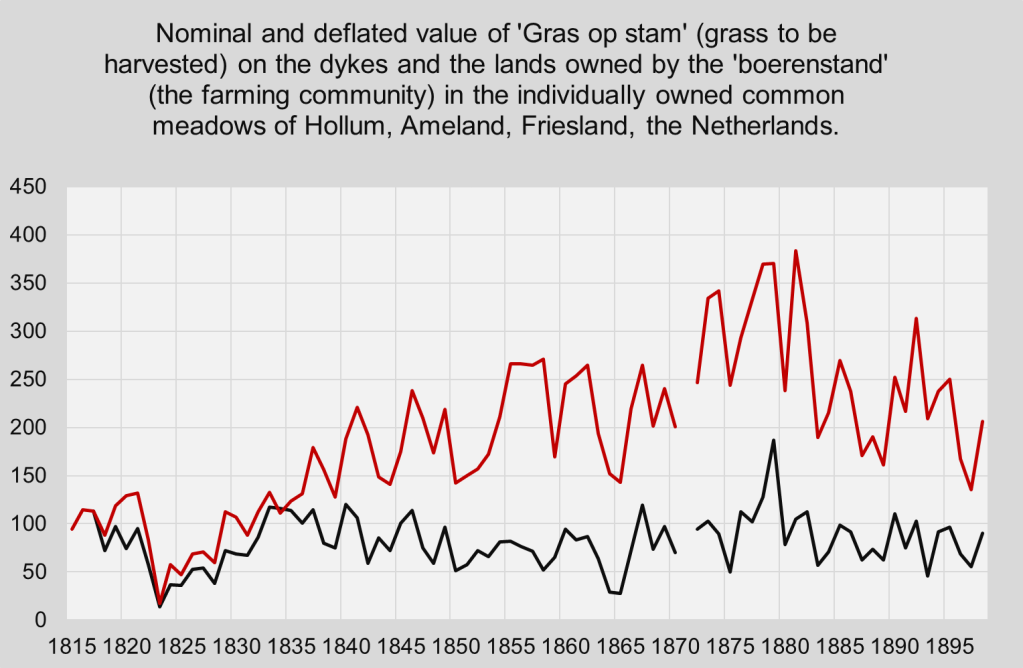

As resources were limited, farmers actually cared a lot, especially about use rights and the distribution of these rights. The caretakers, chosen by the commons members, counted every cow, every horse, and every sheep on the island before the grazing season started and set precise dates for its beginning and the end. They also organized maintenance of dykes, ditches, and whatever. Simplified: there were 576+576+88,5+126 so-called ‘achtendelen’ (ownership shares in the commons). Each achtendeel gave the right to graze one cow-unit and was also tied to multiple small parcels of land in the hay lands, each parcel having precisely defined maintenance duties coupled to parts of the dykes and ditches etc. etc. The basically unpaid caretakers (a lot of expenses were paid, but actual renumeration for the job was equal to one weeks’wages) managed this system.

The point:

Commons as organizations are, by their very nature, essence, and concept, long-term economic-administrative units where clear rights and duties are administered down to the individual task and person. This requires a detailed delimitation of tasks and individual and communal property rights and duties. Without this, commons do not exist. And neither can anything like a ‘tragedy of the Commons’ exist. It’s the absence of Commons that leads to tragedy.

But this means they can run into trouble when the situation becomes opaque. This happened when the somewhat archaic rights were not redefined into more modern rights. The resulting unclear situation meant that (up to 1896, when, to everybody’s surprise, a judge suddenly disbanded the commons) an excessive amount of time and money of the members and caretakers of the commons would be used to redefine their ownership rights. There were traditional use rights and maintenance duties, but no deeds described in any detail anything that resembled modern ownership. In 1831, the people triangulating the island as part of the national cadastral survey needed to understand this. But they didn’t. In a somewhat colonial fashion, they ascribed every piece of land not used as pasture, meadow, or arable land to the ‘Domeinen’, the government organization managing lands seized after the Revolution of 1795. To an extent, this was right as maintenance duties for dunes bordering the sea were transferred to Domeinen. Domeinen did this by planting Beach grass every year. However, use rights were still exercised by farmers. At the same time, maintenance duties did not apply to the extensive dune valleys, which were also transferred to Domeinen. For a time, however, nobody cared.

Farmers were still allowed to graze their cows in the dunes, which, according to the cadastral administration, were suddenly owned by Domeinen. Also, Domeinen had to pay the new, post-1831 land tax. It was a win-win-win situation for the farmers, while Domeinen didn’t seem to be bothered. The only clear right of Domeinen was the right to rent out the rabbit hunt, but they gave up on this in 1829. Farmers started to free-ride on these uncommons (maintained by Domeinen but used by the farmers) as they allowed their cows to graze newly planted grass.

At first, this was not too much of a problem. But the island eroded on the south side and, as islands in the Waddensea area do, shifted from west to east, which meant that the area of Grie, used as pasture and dunes, also used for grazing, diminished. Also, the number of cows, which for several reasons had been relatively low in the first decades of the 19th century, slowly increased to the ‘traditional’ level set by the ‘achtendelen.’ A smaller island had to accommodate more cattle, while ownership duties were not well-defined. Overgrazing took place, especially during the ‘vrijgang’, and sand drift became an ever more significant problem, leading to serious damage of agricultural lands and, as the dunes disappeared, an increased risk of flooding. Nobody set limits. The dunes were, de facto, neither part of the commons nor well-maintained state property.

This all changed in 1872. A well-connected entrepreneur wanted to reclaim the shallows between the island and the mainland and convinced Domeinen that the island’s erosion had to stop. In, again, a somewhat colonial style, it rented out its land in two huge parcels of around 1.500 hectares to two farmers who either had to evict the cows of other farmers from the area or to sublet parts of it to the members of the commons, which were very well aware that, for centuries, they had had the right to graze their cows in the very dunes, Grie and valleys of these parcels for free. A long story short, largely thanks to the tenacity of the mayor, the mistakes of the original cadastral survey were retracted, renting out the lands was discontinued, and a lot of the traditional use rights of farmers were transformed into modern ownership rights of these same commons (even when they had to compensate Domeinen for 50 years of property taxes paid). At the same time, the remaining state properties along the sea coast were fenced using the relatively new barbed wire technology. Unlike earlier endeavors, farmers accepted this and did not demolish these fences. The plans of the entrepreneur were, ultimately, abandoned.

The island’s shifting was, at the time, beyond anybody’s capabilities. The erosion of the southern Grie had, in the forties and again thanks to the same major, been halted by a combination of a dyke stretching into the Waddensea and rocks along the eroding stretches. But until the re-distribution of land ownership and the use of barbed wire to end the free riding of farmers, the sand drifts continued. In my opinion, this free-riding was an example of ‘the tragedy of the uncommons.’

But the story is longer. In 1896 to everybody’s surprise, a judge disbanded the commons, the government built dykes along the still-eroding southern shore, and lands were redistributed. Investors from the mainland bought quite some of these lands and established some large farms. But, ‘when all seemed lost’, former members of the dissolved hybrid commons of Buren founded a limited company, bought the remaining undyked lands, tied grazing rights to shares in the same way as they used to be tied to the ‘achtendelen’ and continued to graze their cows in the still outer dyke easter Grieën of the island. Even when today, in 2024, the cowherd does not walk barefoot anymore but rides a quad.