Introduction< The 2024 Sveriges Riksbank Prize for Economic Sciences has been awarded to Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson and James Robinson for work on the influence of institutions on long-term economic progress and growth. Much has been written about this, for instance by ´Pseudoerasmus´ here and by Radford here. In this article, an ´in-depth´ analysis of a part of the work leading to the the prize, an analysis of the long-term impact of the Dissolution of the English monasteries (1535) on the economy, will be provided.[1] Developments in England are compared with developments in Fryslan (formerly: Friesland), a province in the northern Netherlands. Contrary to the situation in England, in Fryslan, not the land-owning gentry but land-renting and using farmers were the heroes of

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: agriculture, Farming, fryslan, gentry, history, Innovation, Institutions, monasteries, productivity, Sustainability, sustainable-agriculture, Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

Introduction<

The 2024 Sveriges Riksbank Prize for Economic Sciences has been awarded to Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson and James Robinson for work on the influence of institutions on long-term economic progress and growth. Much has been written about this, for instance by ´Pseudoerasmus´ here and by Radford here. In this article, an ´in-depth´ analysis of a part of the work leading to the the prize, an analysis of the long-term impact of the Dissolution of the English monasteries (1535) on the economy, will be provided.[1] Developments in England are compared with developments in Fryslan (formerly: Friesland), a province in the northern Netherlands. Contrary to the situation in England, in Fryslan, not the land-owning gentry but land-renting and using farmers were the heroes of agricultural innovation after (and also before) the Dissolution of the Monasteries (1580). After about 1560 the Frysian countryside witnessed a genuine industrial revolution as wind power was used to drain and improve land on a massive scale – the number of wind drainage mills per Frysian parish was about 100 to 200 times as large as the number of textile mills per parish in England. The Dissolution in Fryslan did affect the distribution of agricultural income but had, contrary to the situation in England, little to do with the unleashing of the new powers of production.

The work investigated is the NBER working paper ´The long-run impact of the Dissolution of the English monasteries´ by Leander Heldring, James Robinson (one of the Riksbankprize winners) and Sebastian Vollmer (HRV, 2014, revised in 2021). According to the authors, the Dissolution of the English Monasteries in 1535 contributed to the Industrial Revolution and the rise of England to global power

Monastic lands were, according to the authors, less burdened by feudal bonds than other lands, bonds which, according to the authors, sometimes lasted well into the twentieth century in England. Seizing and selling these lands by the government enabled private entrepreneur-gentlemen, or ´the gentry´, to purchase these lands. In counties where a sizeable area of monastic lands was nationalised and subsequently sold and re-sold, farming was adapted to relative prices, enabling a more productive land use. In the end, this led, among other things, to a boost to industrialisation, operationalised as the number of English counties with a textile mill (4%) as well as the average amount of mills per county (0,16)). This, in turn, contributed to the English rise to power in the 18th century. In their words (´marketability´ means the possibility to sell land):

´Taken together, our findings link the spread of the market, brought about by the Dissolution, to economic and social change. These changes have been hypothesized to be crucial preconditions for the Agricultural Revolution and ultimately industrialization, but have not been tested before. Our results suggest that the end of monastic restrictions on the marketability of 1/3 of the land in England and relative incidence of customary tenure, itself directly linked to feudalism, were important for fundamental changes within England. The lagged abolition of feudal land tenure in France and Germany may be behind why England pulled ahead on the world stage in the eighteenth century. Continental Europe only transformed after their political revolutions in the nineteenth century finally did away with servile labor and customary land tenure relationships (Acemoglu, Cantoni, Johnson and Robinson, 2011).´

The dataset HRV use is stunning. The correlations they find are highly interesting. The questions they try to answer are of prime importance. Of course, correlation is not causation, and correlations are descriptive statistics. However, their narrative based on these statistics is tantalizing – even when it does not necessarily lead to the conjectures in the citation above.

Given the scope of the HRV study, it’s paramount to compare the long-run impact of the Dissolution of the monasteries in England with the consequences of the Dissolution in other areas, in this case, Friesland. Did, in other places, the dissolution of the monasteries also contribute to the modernisation, industrialization and increased power of entire countries? Data for Fryslan do not go back as far as the English data (HRV start with the 1086 Doomsday Book, which contains data for 1066). Even as late as the 16th century, we have less data for Friesland than for England. Some information is, however, available. This information will be used to answer (or at least discuss) whether the narrative about the long-term impact of the English Dissolution can be generalized – or not.

Friesland

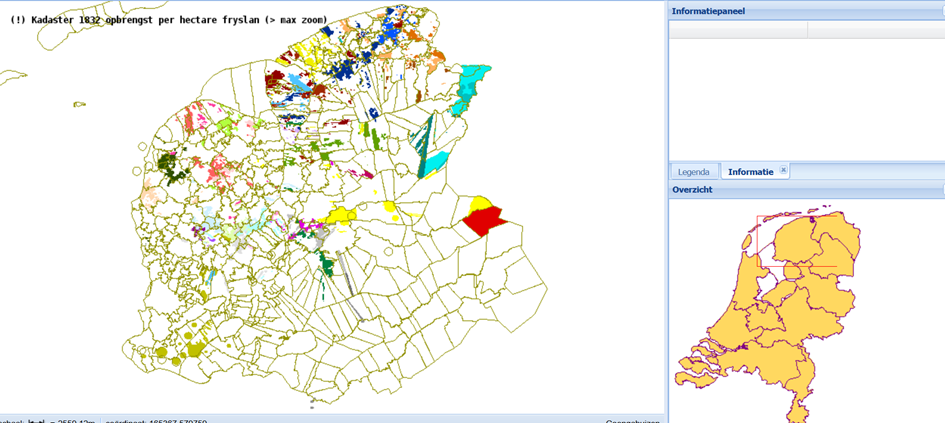

Map 1. Monastic lands in Fryslan around 1580 and the location of Friesland in the Netherlands (present-day borders, changes in borders of the Northern Netherlands were, however, limited).

Source: www.HISGIS.nl, ´Fryslan´ and using the layers ´parochie grenzen (borders of parishes´ and ´kloosterlanden (monastic lands)´

The province of Fryslan is about the size of the English county of Kent and consists of the larger part of the clay soil salt marshes, which, in Kent, can be found between Gravesend and Whitstable. Monastic lands were primarily located in this, if well kept, protected by dykes and well-drained, highly fertile area. To this clay soil area, the fenlands in the middle and south of the province, which also required draining, and relatively poor sand soils in the east and southeast can be added. As is apparent from map 1, Frisian monasteries owned extensive amounts of land, comparable with the situation in England. These were mainly located in the clay soil area.

In 1580, as part of the Dutch Revolt, the protestants seized power in Fryslan. Consequently, the lands of the Frisian monasteries were confiscated and redistributed to the government as well as to all kinds of orphanages and the like. Local parishes owned about as much as the monasteries. These lands were, just like the local churches, seized from the catholic church and distributed to new Protestant parishes. Contrary to the situation in England, the lands now owned by the government were not directly sold, only from 1630 onwards. Did this nationalization and re-distribution of the Frisian monastic lands in Friesland lead to the same processes as in England? To answer this question, we first will state some stylized facts about Frisian agriculture:

- The coastal provinces of the Netherlands (Holland, Zeeland, Groningen, Fryslan, plus large parts of Overijssel and Utrecht, which bordered the Zuiderzee) were and are a drained swamp, originally consisting of pet bogs and salt marshes as well as some dunes. Slowly, these bogs and marshes were drained and protected against storm surges – a process with many setbacks which would last many centuries. Innovations in agriculture in this area have always been connected to innovations in drainage, coastal defences, and public and private water management.[2]

- Many of these areas consisted, at least after 1500, almost entirely of grasslands. Farming in extensive areas of Fryslan was highly specialized in either dairy or hay production. Interestingly, the extent to which the ´hay areas´ were specialized in hay had a clear relation with the prices of butter relative to hay, as Ypey demonstrated as early as 1781.[3] Farmers were keenly aware of market trends and adjusted their production strategies accordingly. One example: in Hennaarderadeel, farmers specialized in hay production bought horses during the summer to sell them again in autumn. At the latest, since 1530, market-oriented farming dominated agriculture in Fryslan, except in the utter southwest and southeast.[4] The Pax Habsburgiana, starting after the pacification of Friesland by Charles V between 1515 and 1528, was highly beneficial to farming (and to society in general) for one reason: this enabled Frisian farmers to export ever more products to the rapidly expanding cities in Holland.

- The extent to which farming depended on wage labour is unclear for around 1530. But around 1570 (i.e. before the dissolution of the monasteries), however, crucial activities like the hay harvest (especially mowing) were critically dependent on ´gangs´ of labourers who travelled the countryside, even when these did not yet come from Germany, as was the case from somewhere in the 17th century onward.[5] As far as we can investigate, monetized, market-oriented and wage labour-dependent farming seems to have been quite normal since, at the latest, 1540 and probably earlier.

- The dissolution of the monasteries influenced the distribution of agricultural income, as larger sums went to the Frisian state and mainly city-based charities. But it hardly affected farming. Farming was dominated by farmers renting lands; existing rent contracts for monastic lands were continued. ´Demesnes´ farmed by the monasteries were split into two or three parts and rented out. This seems to have been a fast and smooth process.

- After 1630, provincial lands were sold (except for the 5.000 hectares of the Bildt area). After 1640, enabled by some political changes, a rapid process of oligarchisation was set, meaning that ever more lands (including political rights tied to ownership of particular lands) were owned by ever fewer families.[6] This, however, did not influence the use of land even when it did influence the distribution of agricultural income.[7]

- Summarizing: the dissolution of the monasteries led, but only after 1630 and hence a century later than in England, to a situation where more land (especially the more fertile lands) than ever was owned by private persons instead of organizations like the government or monasteries. Agriculture was market oriented and wage labor dependent. Aside from this, in the adjacent Groningen province, the monasteries were dissolved in 1594, while the monastic lands were sold even later. It´s another story, but this seemingly small difference with Friesland led over time to an entirely different system of land renting. Rents in Groningen became fixed, while those in Friesland stayed flexible. This might have stimulated Groningen farmers to invest even more significant sums in their lands than Farmers in Friesland did.

- Infrastructural investments, such as the successful improvement of coastal defences after the ´Groot Arbitrament´ of 1533, were highly beneficial to farmers.

Taken together, agriculture in Friesland was, around this time, on average more market oriented and wage labour dependent than in England. Feudal bonds were absent. Between 1530 and around 1580, it also greatly profited from the Pax Habsburgiana, while after 1595, it greatly profited from the Pax Hollandica. I did not do any systematic investigation, but I suspect that after 1596, Fryslan, also compared with other Dutch provinces, was the area least affected by war of the entire area consisting of Northern Germany, the United Netherlands and present-day Belgium and the UK (it might, however, be that some areas in England escaped the destruction of the English civil wars between 1642 and1651).

Considering this situation and following the suggestions of Heldring, Robinson and Vollmer, the question is whether we notice any kind of ´industrial revolution´ in this wealthy, market-oriented, wage labour-dependent and peaceful area? In my opinion, we do. But let me redefine an industrial revolution first:

`An industrial revolution is any process where non-muscle power is used to mechanize production processes which hitherto had dependent on natural processes or human or animal muscle power and which does not just lead to the replacement of human or animal power but also the improvements in productivity as well as quality and quantity of production´.

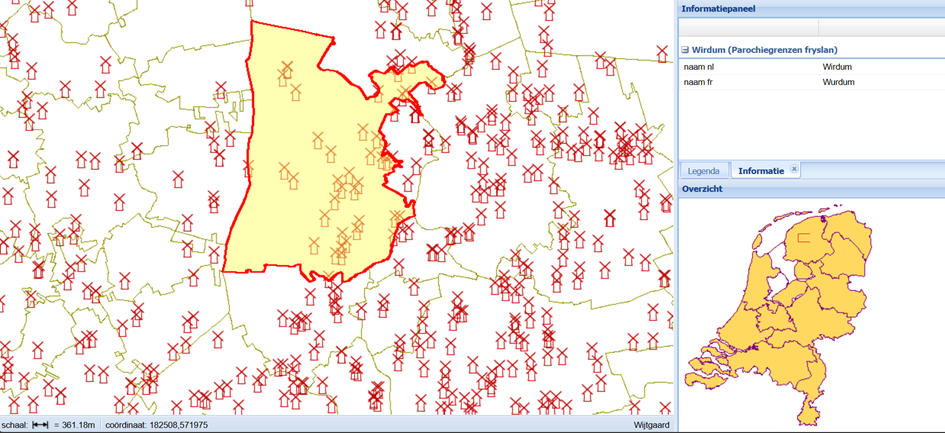

This is precisely what happened in Fryslan. Drainage of agricultural lands was revolutionized by using small drainage windmills. The first sources mentioning such mills are from about 1560, indicating that they had already been used for some time. Eventually, they were counted by the thousands, enabling the draining of the swamp. This also required micro-investment in land maintenance, like digging ditches. It was crucial to enable the manuring of pastures and part of the haylands. A GIS dataset of these mills is available: Map 2 shows details for roughly the same area as the area covered by the windmill insurance data of Table 1 below. As HRV use parishes as their primary unit, the borders of parishes are indicated, and the parish of Wirdum is highlighted. Many parishes counted dozens of mills. Compare this with the average of 0.16 textile mills in the English parishes and the 4% of English parishes where textile mills were present.

Map 2. Windmills in and around the parish of Wirdum, ca. 1800.

Source: see map 1 and also selecting for ´windmolens´ (windmills)

As this article is about investments, it is essential to know the value of the windmills. We do have some data on this. From 1816, Frysian mutual insurance based in Wirdum started to ensure, among other items. The area roughly coincides with the datapictured as well as around it. Table 1 shows the values. The drainage windmills had, on average, one-eighth of the value of corn mills, oil press mills or sawing mills. This was somewhat than the average income of a fully (year-round) employed labourer and hence a considerable sum. To this, serious maintenance costs must be added (sails, moving wooden parts in a wet environment). Around this time, smaller mills started to be replaced, by combinations of farmers, with much larger polder mills, which were used to drain larger areas, which were about as expensive as industrial windmills. Total investments were hence considerable, I do not hesitate to call this, considering the number of mills, a veritable industrial revolution, indeed when we compare this with the 4% of English counties where, according to Heldring, Robinson and Vollmer, one or more textile mills were present. The number of insured windmills (117, in a limited area of Fryslan) only four years after the company’s start underscores the importance of these mills to agriculture. Heldring, Robinson and Vollmer calculated an average of 0,16 mills per municipality. In Friesland, this might have been closer to 50, or three hundred times as high (there were 31 municipalities and at any point at least 1500 windmills).

Table 1. Average and standard deviation of insured value (guilders) of windmills insured in 1816-1822 by the OBAS mutual insurance organization in Wirdum, Fryslan.

Drainage windmills Industrial windmills

Average value 361 2,636

Standard deviation 183 1,125

n 117 7

Source: Tresoar 102, Friese onderlinge verzkeringsmaatschappijen voorgangers Avéro, no. 493.

Looking ahead to the modern period (as HRV also do), another industrial revolution took place after about 1880. Fryslan was an important producer of butter and cheese, and from 1880 on, farm production was rapidly replaced by factory production, a process during which three significant transformations took place. First, the transfer of production to factories. Second, the successful drive to change the market structure in favour of the farmers by introducing cooperatives.[8] Third, in cooperation with the government and research institutions, the milk payment system was changed by introducing ´Multi-Factor Pricing´, paying not just for fat but also for milk protein.[9] Farmers did not just change relative prices – they changed the very nature of prices and pricing! The power of branding was also quickly embraced, and Frisian dairy cooperatives owned a leading global brand (Friese Vlag) in the market for condensed milk. To an extent enabled by colonial ties to Indonesia. But also by the economies of scale of the vast condensed milk factory established by 30 cooperations in Leeuwarden in 1913. The point: these market-oriented farmers did not just react to market prices by investing in modern production processes – they also changed the very nature of the market by establishing cooperatives, introducing new methods of pricing, transferring dairy production from farms to the factory and reaping the benefits of increasing returns to scale by joining together in the production of a new product like condensed milk. This was not based on a landed gentry’s initiatives but on a class of specialized and reasonably sized independent farmers specialising in producing, at first, dairy and milk. The roots of this farming system go back centuries – to before the Dissolution of the Frysian monasteries. Yes, giant leaps, but that’s what HRV also do.

Conclusion

Unlike the situation in England, where the ´gentry´ were, according to HRV, unleashing the forces of production, the heroes of investment in Friesland were the actual farmers, individually as well as cooperatively, like in the instance of the mutual insurance companies on which part of the data presented here are based. The mass use of drainage windmills indicated, at least in my opinion, a veritable revolution in energy use in agriculture in combination with a clear improvement of the quality of land, as the use of mills required micro drainage infrastructure and enabled manuring of a more significant part of the pastures and haylands. This was, however, crucially dependent on the government’s proper maintenance of coastal defences.

Especially after 1640 and, incidentally, just like in England after the sale of the cloister lands owned by the government, we do see the change of some rural landowners into an oligarchic ´gentry´, often (but not always) from families which around 1500 already belonged to the rich and powerful.[10] At this time, most monasteries had been torn down. The ´Frysian gentry´ used the money from their lands to build beautiful county estates (most of which nowadays have been demolished, too). There are, however, few signs of the contributions of this Frysian gentry to investments in lands and new technologies. Farmers using these lands unleashed new forces of production, not just reacting to but also changing relative prices, markets and even pricing systems. Not the gentry owning these lands. In Fryslan, changes in ownership of land affected the distribution of income. The influence on production of such changes was however pretty limited. Caveat: in the area I´m writing about, the average size of farms, as well as the distribution of farm sizes, did not change too much in these centuries. If changes in ownership had influenced these sizes, things might have turned out differently.

[1] Heldring, Leander, James A. Robinson and Sebastian Vollmer, (2014 (2021)). ´The long-run impact of the dissolution of the english monasteries´, NBER Working Paper 21450

[2] Draaisma, Kees (2017), ´Een nieuwe kijk op Caspars dijk´, It Beaken 79 18-76; Schroor, Meindert (1999), ´Droogmakerijen in Friesland (1600-1800)´, Noorderbreedte 89 73-77;. Knibbe, Merijn (2014). ‘De kerk, de staat en het vredesdividend. Pachtopbrengsten van kerkelijke goederen in Friesland’, De Vrije Fries 94 251-278

[3] Ypey, Nicolaes (1781). Een drietal gekroonde prijsverhandelingen over de Vraage of het voor de provincie Friesland voordeliger zij, de uitvoer van hooi eens en voor al te verbieden; ofwel altoos onbepaald open te stellen etc. etc. (Three Price Winning Treatises About The Question if Forbidding Export of Hay For Once and All or to Allow it Forever is More Profitable for Friesland etc. etc.) (Harlingen).

[4] Knibbe, Merijn (2006). ´Lokkich Fryslan. Landpacht, arbeidsloon en landbouwproductiviteit in het Friese kleigebied, 1505 – 1830´, Historia Agriculturae 38. Wageningen/Groningen. Knibbe, Merijn (2011). ´Agricultural productivity in the coastal and inland area of Friesland, 1700-1850´ in: Growth and Stagnation in European Historical Agriculture Volume 6 83-115 Brepol

[5] For the area around Hitzum ca. 1570: Slicher van Bath, Bernard (1956), ´Het rekenboeck van Rienck Hemmema historisch beschouwd´ in: Rienck Hemmema . Rekenboeck of memoriael, Estrikken . rygelytse tekstenen studzjes op it gebiet van de Fryske filologie´ 14 VII-LIX; for the area around Leeuwarden in the decades after 1570: Schroor, Meindert, ´Inleiding. De Leeuwarder weeshuisreekeningen 1541-1608´ in Schroor, Meindert (2021), De Leeuwarder weeshuisrekeningen 1541-1608. VIII-LXV.

[6] Cornelis Jan Guibal (1934), Democratie en Oligarchie in Friesland tijdens de Republiek, Van Gorcum’s Historische Bibliotheek Deel IX (Assen). Faber, Jan (1970), ‘De oligarchisering van Friesland in de tweede helft van de zeventiende eeuw’, AAG bijdragen 15 39-61; Spanninga, Hotso (2001), ‘Kapitaal en fortuin. Hessel van Sminia (1588-1670) en de opkomst van zijn familie,’ De Vrije Fries 81 9-52; Spanninga, Hotso (2012) Gulden Vrijheid. Politieke cultuur en staatsvorming in Friesland 1600-1640, (Hilversum).

[7] Hotso Spanninga (2012’, Gulden Vrijheid. Politieke cultuur en staatsvorming in Friesland 1600-1640. (Hilversum).

[8] Knibbe, Merijn and Marijn Molema (2018). ´Institutionalization of Knowledge-based Growth Illustrated by the Dutch-Friesian Dairy Sector, 1895–1950´, Rural History: Economy, Society, Culture, 29 no. 2, 217-35; Tjepkema, K. J.P. and J.P. T Wiersma (1959), Erf en Wereld (Drachten).

[9] Knibbe, Merijn, Marijn Molema and Ronald Plantinga (2023 ). ´7. Fair value? The price of milk and the intricate path of bio-based productivity growth in Dutch dairying, 1950-1980´ in: From breeding & feeding to medicalization. Rural History in Europe 17 (Turnhout).

[10] Langen, Gilles de and Hans Mol (2022). Friese edelen, hun kapitaal en boerderijen in de vijftiende en zestiende eeuw. De casus Rienck Hemmema te Hitzum (Amsterdam).