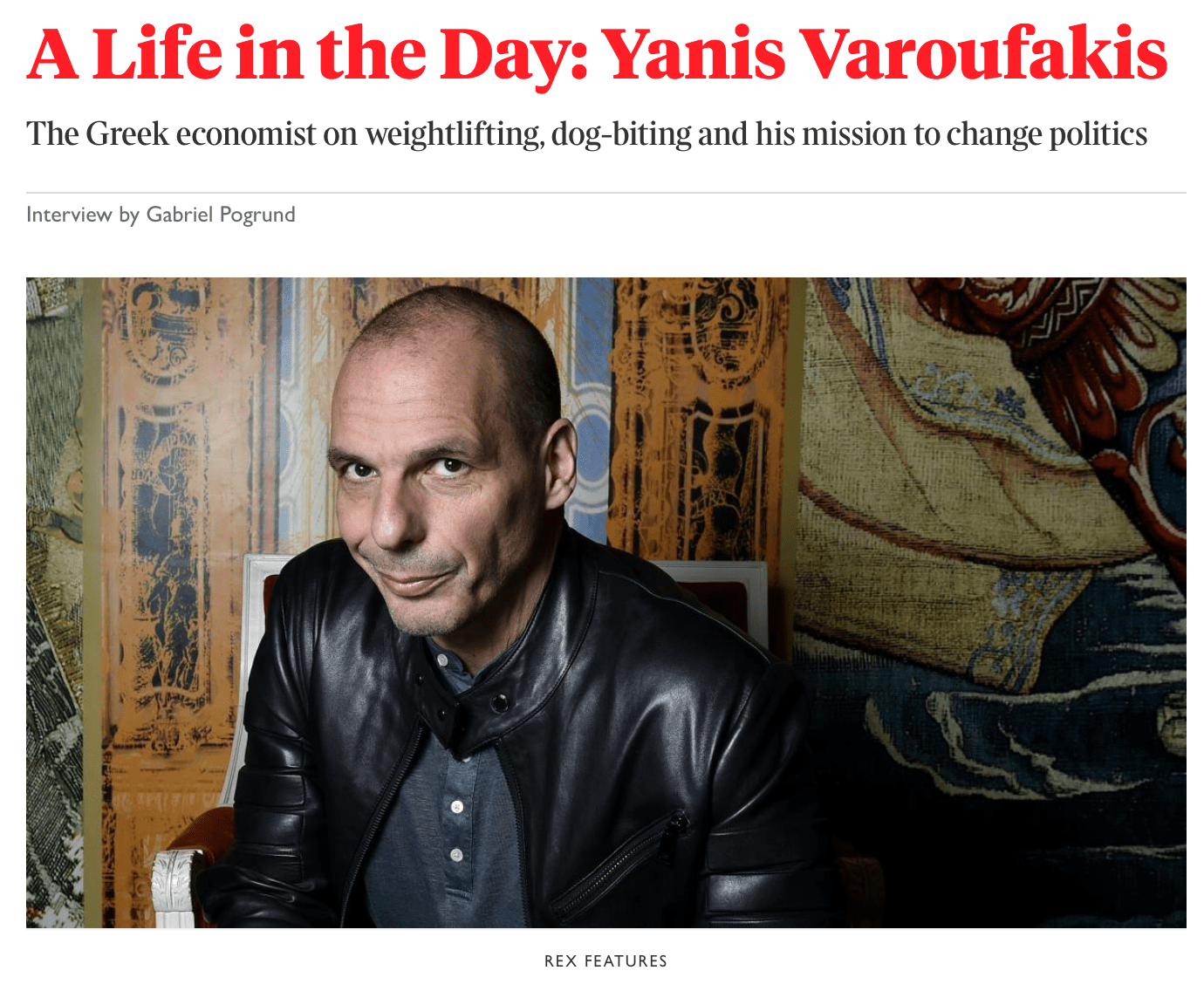

On the occasion of the publication of ‘Talking To My Daughter about the Economy: A brief history of capitalism‘, the Sunday Times published this interview, in the context of their series ‘A Day in the Life of…’ Apologies for the lifestyle-like style and content… Interview by Gabriel Pogrund Best advice I was given A statistics professor told me: “Say what will happen or when it will happen. Never predict both as you’ll end up with egg on your face” Advice I’d give To be moderate, you have to constantly subvert the dominant paradigm What I wish I’d known That the worst enemy lies within your own camp Born in 1961 in Athens, Varoufakis, 56, served in Greece’s government as the minister of finance during the

Topics:

Yanis Varoufakis considers the following as important: Books, English, Interviews, Lighthearted, Talking to my daughter about the economy: A brief history of capitalism, The Sunday Times

This could be interesting, too:

Michael Hudson writes Something Nutty Emerging Here

Michael Hudson writes Why Banking Isn’t What You Think It Is

Michael Hudson writes The Horizon Nears on America’s Free Financial Ride

Michael Hudson writes Capital as Power in the Polycrisis

On the occasion of the publication of ‘Talking To My Daughter about the Economy: A brief history of capitalism‘, the Sunday Times published this interview, in the context of their series ‘A Day in the Life of…’ Apologies for the lifestyle-like style and content…

- Best advice I was given A statistics professor told me: “Say what will happen or when it will happen. Never predict both as you’ll end up with egg on your face”

- Advice I’d give To be moderate, you have to constantly subvert the dominant paradigm

- What I wish I’d known That the worst enemy lies within your own camp

Born in 1961 in Athens, Varoufakis, 56, served in Greece’s government as the minister of finance during the 2015 bailout crisis, before resigning in protest over austerity measures. He has a flat in Athens and a villa on the island of Aegina, which he shares with his wife, Danae Stratou, an artist, and her two children. Varoufakis has a daughter with his first wife. He is the author of several books on the global economy.

Rising early is the only way I can work. I wake at 5.30am and put the coffee machine on. By the time it’s ready, I’ve finished my press-ups: three sets of 80. I’ve been doing them for 50 years.

Before I get to my desk, my Labrador, Mowgli, and I have a big hug. I bite him, he bites me.

Then, for two or three hours, I’ll write intensively, the equivalent of a whole day’s work. In my most recent book, I wrote to my 12-year-old daughter about capitalism. My personal tragedy is I’ve never lived with Xenia. She lives in Australia with her mother, and so the clock’s always ticking: counting down when we’re together, or until we’re together. As a child, she would fall asleep as I read her bedtime stories on Skype, but this book brought me closer to her without a ticking clock.

After I finish writing at 10am, my wife, Danae, and I have breakfast: tea and Greek yoghurt with chopped-up fruit. This is a special part of my day. Every time, it feels like a first date.

Before I actually knew Danae, I’d fallen in love with her work. I came across an exhibit in Athens and assumed she was a 90-year-old woman — it was a mature piece of art and the name sounded old-fashioned. Then I met her and thought: “Now I’m in trouble!”

Nothing happened because we were both married, but two years later, we met by chance in a London restaurant. The rest is history.

My big project at the moment is the Democracy in Europe Movement [DiEM25]. Our aim is to spread a new politics through the democracy-free zone that is the EU. It will probably fail, but we don’t give a damn. It’s fun trying. For the European elections, we’re putting up transnational candidates: Greeks in Germany, Italians in France. I’ll probably have to stand. I’m dumbfounded by career politicians, though, and think anyone keen to be a minister should be disqualified.

At 1pm, I’ll have lunch. Danae and I have something cold: our latest craze is black lentils with Greek white goat’s cheese, cherry tomatoes and salad. I used to cook, but my time in government ended that. I lost the luxury of time. Reflecting on that period, I’d say my relationship with Alexis Tsipras [the Greek prime minister] is beyond repair. To justify his U-turn [over the EU’s austerity package], he has to tell himself stories that, deep down, he knows are false.

I’m not enthusiastic about the EU, but my view remains that, instead of leaving, one should stay and veto the hell out of everything until we can have a serious conversation about reform.

Corbyn and I are very close and I’m pleased he’s come to my original position: that in terms of Brexit, Britain should have a long transition period and give itself a chance to prepare. Then you can leave but maintain good links, and potentially come back in if the EU shows it’s transformed itself.

After an afternoon of reading and writing, I’ll go to the gym at 7pm. If I don’t go, my back starts to hurt. I used to bench-press 150kg. Now I can’t do more than 90.

Two or three nights a week, we’ll go out with friends, whether it’s the theatre or a film or to eat.

For dinner, we’re keen on simple grills with meat or fish and a big salad with balsamic and figs and tomatoes. Danae has a glass of wine. I enjoy a shot or three of raki.

At the end of the evening — and that can be anywhere from 9pm to 3am — we crash on the sofa, listen to music and fall asleep.

Talking to My Daughter About the Economy: A Brief History of Capitalism by Yanis Varoufakis is out now (Bodley Head £15)