Three years ago, today, the people of Greece staged a rebellion against their debt bondage. Though this rebellion was overthrown from within almost immediately, it remains a remarkable testimony to the power of a people to say No to the oligarchy, to wrestle control of the narrative of their circumstances from the inanely authoritarian elites, and to overcome the fear which a tiny minority uses to take the demos out of democracy. On the 5th of July 2015 the people of Greece wrote a stupendous chapter in the annals of the global struggle for democracy. It should be remembered as such, independently of what happened next. For, during these three days that shook Europe, They turned a deaf ear to the local

Topics:

Yanis Varoufakis considers the following as important: Adults in the Room, Books, English, Finance Minister, FinMin2015, Greece, Greek crisis

This could be interesting, too:

Merijn T. Knibbe writes ´Extra Unordinarily Persistent Large Otput Gaps´ (EU-PLOGs)

Robert Skidelsky writes A Tale of Frankenstein – Lecture at Bard College

Merijn T. Knibbe writes In Greece, gross fixed investment still is at a pre-industrial level.

Robert Skidelsky writes In Memory of David P. Calleo – Bologna Conference

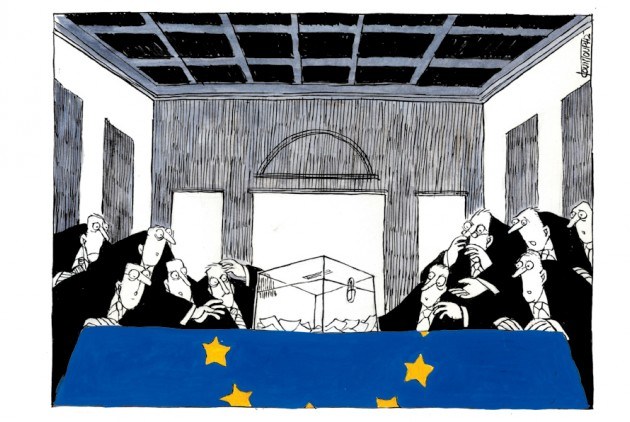

Three years ago, today, the people of Greece staged a rebellion against their debt bondage. Though this rebellion was overthrown from within almost immediately, it remains a remarkable testimony to the power of a people to say No to the oligarchy, to wrestle control of the narrative of their circumstances from the inanely authoritarian elites, and to overcome the fear which a tiny minority uses to take the demos out of democracy.

On the 5th of July 2015 the people of Greece wrote a stupendous chapter in the annals of the global struggle for democracy. It should be remembered as such, independently of what happened next. For, during these three days that shook Europe,

-

They turned a deaf ear to the local oligarchy’s hysterical threats

-

They laughed at the tv stations’ warning that voting No (OXI) to the troika’s ultimatum would bring Armageddon

-

They shrugged their shoulders when the European Central Bank, after having engineered a six-month long bank run, tried to throttle our democracy by closing down the banks (to punish our government for daring give the people the final say on the troika’s ultimatum).

And,

-

They flocked at the polling stations to deliver an astounding, brave, unprecedented 62% rejection of the international and local power-hungry establishment’s ultimatum.

Every 5th of July Europe’s and Greece’s establishment revisits its paroxysm of anger at having lost control of the Greeks – even if briefly. They just cannot fathom the fact. They feel compelled to vilify those who dared vote No on the 5th of July 2015. And, of course, they demonise any politician who underpinned that No vote and who continue to honour it to this day.

This is, of course, why the troika of lenders, together with their Greek agents, continue to vilify me, personally, especially around the beginning of July… As I promised in my letter of resignation in the wee hours of 6th July 2015, I wear their loathing as a badge of honour.

Below I copy the part of my ADULTS IN THE ROOM memoir pertaining to those magnificent three days.

Square of hope and glory

On the afternoon of Friday 3 June, as the working day drew to a close, I breathed a sigh of relief. A week of closed banks was almost over. Despite the long queues for ATMs and the uncertainty of what awaited us the following Monday, there had been no violence, no panic, no civil unrest. Greeks proved their credentials as a most sensible lot.

The media, however, had managed to fall below their already absurdly debased standards, competing with one another to find the most innovative ways to scare the public away from voting NO. Much of their reporting of the NO sponsors and supporters would in other countries be deemed incitement to violence. Their opinion polls consistently predicted that YES would win with more than 60% of the vote while their commentariat foamed at the mouth at the government’s audacity in holding the referendum against the creditors’ wishes. Meanwhile, the parliamentary opposition was managing to persuade its supporters to take to the streets in some numbers, waving EU flags and placards boasting, “We are staying in Europe!”[i]

Later that Friday afternoon, I received an email from Klaus Regling, the Managing Director of the European Stability Mechanism, the Eurozone’s bailout fund. It was a reminder that he had the legal right to demand from me full and immediate repayment of the €146.3 billion lent to Greece as part of the first two bailouts. It was phrased in such a way as to suggest that I was personally liable, not least because, as finance minister, my name was on the loan agreement. It was too good an opportunity to pass up. I instructed my office to reply to our main creditor – and to the man who had advised me to default to my pensioners instead of the IMF – with two ancient words. They were the defiant response of the King of Sparta, leader of the 300 men who attempted to resist the entire Persian army at the legendary battle of Thermopylae in 480BC, when instructed by their enemy to throw down their weapons: “Μολών λαβέ” – ‘Come and get them!’

That evening, two rallies were organised, one in favour of YES, outside the ancient Olympic stadium where the first modern Olympics were staged in 1896, and one at Syntagma Square held by the NO campaign. The YES rally was held in the late afternoon. It was large and good-natured. But the NO rally at Syntagma was to be one for the ages. Since I was a boy, I had attended some magnificent, life-changing rallies at Syntagma Square. But what Danae and I participated in that night was unprecedented.

We walked to Syntagma from Maximos with Alexis and other members of the cabinet, their partners and aides. On the way we were mobbed by rapturous supporters. As we approached the square, the crowd’s energy exploded. A sea of five hundred thousand bodies consumed us. We were pulled into its depths by a forest of arms: tough-looking men with moist eyes, middle-aged women with determination written all over their faces, young boys and girls offering boundless energy, older people eager to hug us and shower us with good wishes, a pulsating magma of humanity into whose ebb and flow we surrendered. For two hours, struggling to hold hands so as not to be separated, Danae and I were absorbed into a single body of people who had simply had enough.

People from different generations saw their distinct struggles coalesce on that night into one gigantic celebration of freedom from fear. An elderly partisan pushed into my pocket a carnation and a piece of paper bearing the phrase “Resistance is NEVER futile!” Students forced to emigrate by the crisis who had returned to cast their vote begged me not to give up. A pensioner promised me that he and his sick wife did not mind losing their pensions as long as we recovered their dignity. And everybody, without a single exception, shouted at me, “No surrender, whatever the cost!”

This time, I believed they meant it. The banks had already been closed for a week. The hardship imposed by the creditors was plainly visible. And yet, here they were, these magnificent people saying in one word everything that had to be said: No! Not because they were recalcitrant or Eurosceptic. They craved an opportunity to say a big, fat yes to Europe. But yes to a Europe for its people, as opposed to a Europe hell-bent on crushing them.

That night, as Danae and I eventually found ourselves walking up the marble steps leading to Parliament, the phrase I had been looking for to describe what all this was about finally came to me: constructive disobedience. These people, with their pragmatic defiance, had given it to me. This is what I had been trying to practise in the Eurogroup all along: putting forward mild, moderate, sensible proposals, but when the deep establishment refused even to engage in a negotiation, to disobey their commands and say No! Our War Cabinet had never understood this, but the body of humanity that filled Syntagma Square that night surely did.

[i] The first pro-troika rally took place in Syntagma Squareon 18 June, while I was in Brussels at one of the many Eurogroup meetings. A good ten to fifteen thousand people gathered, making Alexis and the rest of us feel uneasy.

One for true believers

That night, I felt the months of frustration, each terrible moment in Maximos, every disappointment along the way, all the nastiness and the stress had been wiped away, leaving nothing but contentment. And yet, I was still not convinced that the NO campaign would win the referendum. The demonstration at Syntagma suggested support for the cause had risen, but with the banks closed and the media screaming blue murder at anyone who contemplated NO, success looked unlikely. Over dinner with Danae, Jamie and some other friends at an outdoors restaurant in the neighbourhood of Plaka, I was asked if Alexis and Euclid would resign were YES to win. “Alexis will form a coalition government with the opposition,” I predicted, “after most of the true believers resign or are pushed.” Naturally, I would be long gone by then, I said. But Jamie insisted I was wrong. NO would win, he believed, and my leverage with Alexis would skyrocket, as I would have played a large part in delivering it to him. Unconvinced, I nonetheless raised my glass to toast Jamie’s optimism. “Hasta la vittoria siempre!” he said with an intense and committed look – ‘To victory, always!’

On the day of the referendum, I drove to Palaio Phaliro, the southern Athenian suburb where I grew up and where my father still lives. Together we made our way to the polling station. Inside, the majority of voters were ebullient when they saw me, except for one or two who remonstrated angrily that I had closed down the banks. With the television cameras rolling, I replied that the troika had given us an ultimatum and that accepting it would shape his and his children’s future. What we had done was to give him the opportunity to vote for or against it. “Vote YES if you think it is a manageable deal. We are the only government that respected your right to decide. The fact that the troika decided to close the banks down before you got a chance to express yourself is something that only you can interpret.” The man was I addressing seemed to calm down.

After voting, as I was helping my dad walk back to the car, an elderly woman approached me, surrounded by the usual television cameras. With a stern expression she asked me if I knew where she lived. I admitted I did not. “Ι sleep in an orphanage here in Palaio Phaliro. And do you know why they let me? Because your mother worked tirelessly to let vagrants like me have a permanent shelter.” I thanked her for the spontaneous and wonderful remembrance of my mum.[i] But she was not finished. “I bless her every day. But do these bastards know this?”, she said pointing at the cameras and the TV crews. “I bet they don’t and they don’t even care.”

“It does not matter,” I assured her. Even if they didn’t, it was enough that she knew. Nonetheless, I must admit I was perturbed when in the evening news our heart-warming encounter was presented as me being accosted by a homeless woman blaming me for her destitution.

It was not until late that afternoon that I began to sense an historic victory might be on the cards. At my office I composed a piece, in English, for my blog. “In 1967,” I wrote, “foreign powers, in cahoots with local stooges, used tanks to overthrow Greek democracy. In 2015 foreign powers tried to do the same by using the banks. But they came up against an insanely brave people who refused to submit to fear. For five months, our government raged against the dying of the light. Today, we are calling upon all Europeans to rage with us so that the flickering light does not dim anywhere, from Athens to Dublin, from Helsinki to Lisbon.”

By 8pm I could see from the drooping shoulders and morose expressions of TV presenters that we had won. What I did not yet know was the extent of our victory. My fear was that a close shave would give Alexis the excuse to say we had a divided nation and, thus, insufficient support for a rupture with the troika. I told my team that the magic number was 55%. If the votes for NO were any greater, Alexis would have to honour them. I thought carefully of what I would say to the gathered journalists in my ministry’s pressroom in order to give him the necessary impetus to do so. By 9pm, I had written my speech. Traditionally, ministers wait for the Prime Minister to make his statement before issuing their own. So, I waited in my office for Alexis to address the press at Maximos’ pressroom.

At 9.30 I began to feel something was wrong. The results were more or less final, indicating that the 55% mark had been attained, but Alexis was still holed up in his Maximos office. My chief of staff was pressurising me to go to our pressroom as the journalists were getting agitated and were beginning to tweet that something sinister was afoot. I waited until after 10.00pm. I called Alexis. He did not pick up, and nor did his secretaries. Wassily walked in to inform me that other ministers were beginning to speak to the media, issuing lukewarm statements in response to what was in fact an earth-shattering outcome. I could not allow this to continue. Our voters deserved a proper response.

So, at around 10.30, I headed for the pressroom to make my statement with the intention of going to Maximos straight afterward, anxious to discover what was going on there. While reading out my prepared statement I had a very strong feeling that it would be my last as minister. That feeling, combined with the memory of Syntagma Square two nights earlier, made me read it defiantly, brazenly even:

On the twenty-fifth of January, dignity was restored to the people of Greece. In the five months that intervened since then, we became the first government that dared raise its voice, speaking on behalf of the people, saying NO to the damaging irrationality of our extend-and-pretend bailout program. We confined the troika to its Brussels’ lair; articulated, for the first time in the Eurogroup, a sophisticated economic argument to which there was no credible response; internationalised Greece’s humanitarian crisis and its roots in intentionally recessionary policies; spread hope beyond Greece’s borders that democracy can breathe within a monetary union hitherto dominated by fear.

Ending interminable, self-defeating, austerity and restructuring Greece’s public debt were our two targets. But these two were also our creditors’ targets. From the moment our election seemed likely, the powers-that-be started a bank run and planned, eventually, to shut Greece’s banks down. Their purpose? To humiliate our government by forcing us to succumb to stringent austerity. And to drag us into an agreement that offers no firm commitments to a sensible, well-defined debt restructure.

The ultimatum of the twenty-fifth of June was the means by which they planned to achieve these aims. The people of Greece today returned this ultimatum to its senders, despite the fear-mongering that the domestic oligarchic media transmitted night and day into their homes.

Our NO is a majestic, big YES to a democratic Europe. It is a NO to the dystopic vision of a Eurozone that functions like an iron cage for its peoples. But it is a loud YES to the vision of a Eurozone offering the prospect of social justice with shared prosperity for all Europeans.

As I stepped out into Syntagma Square, I saw delight in the faces around me. A proud people had been vindicated and were justly celebrating. The night’s air was full of anticipation and confidence. Alexis’ silence had filled me with apprehension but I refused to believe that Maximos could be sealed off entirely from that intoxicating air of defiance. Surely, I thought, it find its way in through some crack in the walls or through the hearts of the people working there who had also learned their politics at Syntagma Square. And yet, as I walked in, Maximos felt as cold as a morgue, as joyful as a cemetery.=

The overthrowing of a people

As I walked through the main entrance to Maximos, the ministers and functionaries I encountered looked numb, uncomfortable in my presence, as if they had just suffered a major electoral defeat. Alexis was meeting with the President in the adjacent Presidential Palace and would see me later, his secretary informed me. So, I waited in the conference room with other ministers, watching as the last results were declared on television. When the final number flashed up on the screen, 61.31% for NO out of a high turnout of 62.5%, I jumped up and punched the air, only to realise that I was the only one in the room celebrating.[ii]

As I sat and waited for Alexis, I found a message on my phone from Norman Lamont: “Dear Yanis, congratulations. A famous victory. Surely they will listen now. Good luck!” They would listen, I thought, but only if we were prepared to speak up. Sat there, witnessing in slow motion the annulment of our famous victory, I began noticing things about the people around me that had previously escaped me. The men had shed the rough Syriza look andresembled smartly attired accountants. The women were dressed as if for a state gala. When Danae joined me, I realised that not only were we the only happy people in the place but the only ones in jeans and t-shirts. It felt a little like being in one of those sci-fi movies in which body-snatching aliens have quietly taken over.

Eventually, Alexis walked into Maximos and, half an hour later, addressed the nation. Two key phrases in his speech unlocked the vault of his intentions. One ruled out a rupture with the troika. The other was his announcement that he had just asked the President to convene immediately the council of political leaders: on the morning after their decisive defeat, the pro-troika leaders of the ancien regime were being summoned to join him at the discussion table. “He is splitting Syriza up and preparing a coalition with the opposition to push the troika’s new bailout through,” I told Danae. I waited another hour and a half as he held separate meetings with Sagias and Roubatis before he would receive me.

It was after 1.30am when I entered his office. Alexis stared at me and said we had messed up badly.[iii]

“I do not see it that way,” I replied flatly. “There were plenty of mistakes but on a night of such a triumph we have a duty to rejoice and honour the result.”

Alexis asked me if I minded if Dimitris Tzanakopoulos, Maximos’ legal adviser, sat in on our meeting.

“Sure,” I replied. “In fact I want him to be here as a witness.” This was not going to be just another chat.

Alexis asked if the banks would open soon. It was a trick question. He was looking to justify his decision to capitulate. I pretended not to understand, saying that to honour the NO vote, we had immediately to start issuing electronic IOUs backed by future taxes and to haircut Draghi’s SMP bonds. “Without these moves to bolster your bargaining power,” I said, “the 61.3% will be scattered in the winds. But if we announce this tonight, with 61.3% of voters backing us, I can assure you that Draghi and Merkel will come to the table very quickly with a decent deal. Then the banks will open the next day. If you don’t make this announcement, they will steamroll over you.” I explained that I needed only a couple of days to activate this system using the tax office’s website. He pretended to be impressed, so I continued: “This 61.3% result is a capital asset that you must use well. You must manage it with greater respect to the people out there than you showed before the referendum. You must respect yourself more, too. After tonight you have a simple choice. Either you will re-activate our plan, giving me the tools I need, or you will surrender.”

We talked for a long time. We reviewed the previous months, weeks and days. I took no prisoners, providing a litany of his errors, pointing out the ways in which members of our War Cabinet had jeopardised our struggle, often in collaboration with the troika and its operatives. I shared with him evidence of one of them behaving in such a way that bordered on corruption. Looking surprised, he asked Dimitris his opinion: was the person I referred to such a problem? Dimitris answered: “Yes, and even more so.”

The conversation was meandering, so I decided to put it to him straight: would he honour the NO vote, I asked, by going back to our original Covenant? Or was he about to throw in the towel? His answer was elliptical but there was no mistaking the direction in which it headed: towards unconditional surrender. The first time in that conversation that he spoke decisively was when he said, “Look, Yani, you are the only one whose predictions were confirmed. But here is the problem: if any other government had given them what I did, the troika would have sealed the deal by now. I gave them more than Samaras ever would. And they still wanted to punish me, as you had said they would. But let’s face it: they do not want to give an agreement either to you or to me. Let’s be honest. They want to overthrow us. However, with the 61.3% they cannot touch me now. But they can destroy you.”

“Don’t worry about me, Alexi,” I said. “Worry about honouring the folks out there who are celebrating tonight while you are planning to give in. If we were to stick together, activate our deterrent, and show to them that we are united, they would touch neither you nor me. We could propose to them a deal that they could package credibly as their own idea, their own triumph.”

At that point Alexis confessed to something I had not anticipated. He told me that he feared that a ‘Goudi’ fate awaited us if we persevered – a reference to the execution of six politicians and military leaders in 1922.[iv] I laughed it off, saying that if they executed us after we had won 61.3% of the vote, our place in history would be guaranteed. Alexis then began to insinuate that something like a coup might take place: he told me that the President of the Republic, Stournaras, our intelligence services and members of our government were in a ‘readied state’. Again I fended him off: “Let them do their worst! Do you realise what 61.3% means?”

Alexis told me that Dragasakis had been trying to persuade him to get rid of me, everyone from the Left Platform and Kammenos’ Independent Greeks and, instead, forge a coalition government with New Democracy, PASOK and Potami. Dragasakis had assured him that once the agreement with troika had been signed, Alexis could then get rid of New Democracy, PASOK and Potami and bring me back. I told him it was the dumbest idea I had ever heard. He smiled in agreement, using an expression for Dragasakis that is not reproducible here.

“But,” he added, “there is something to the idea of proceeding in two ways, one public one hidden. Publically, we can approach the creditors with a rightwing posture involving a reshuffle that says “we are good kids now”. But, at the same time, hidden from public view, we can prepare the counter-strike.”

“This is bad thinking, Alexi,” I told him. “Look, tonight the people voted. They did not vote NO for you to turn it into a YES.” I told him he had come out and say what I had said in my press statement earlier: that the NO vote had given him the mandate he required to bring about a solution in cooperation with our European partners. “Add some complimentary words for the Commission, the IMF, even for the ECB, to illustrate that we mean it when we say we want a cooperative solution. But simultaneously project strength! None of this nonsense about preparing for an underground war in the catacombs of our state.” I told him that whatever we did now, we had to do it out in the open. We had to state clearly that we were preparing our own liquidity, as we had a duty to do when the ECB was keeping our banks closed. And we had to state clearly that the ECB’s SMP bonds would be restructured according to Greek law, the law under which they were created.

“It will be very difficult for them to give us a solution, Yani,” he said.

“You keep making the mistake of thinking of a solution as something that they give to us,” I replied. “This is not the right way to think about it. They need a solution as much as we do. It is not something that they hand out. We must extract it from them. But this requires that we have a credible threat. The SMP haircut and our own liquidity is exactly that!”

We were going around in circles, our bodies and minds wrecked by fatigue. So I told him that, since he had made his mind up to surrender one way or another, he had better just tell me what he had decided to do now. He said that he was thinking of reshuffling the Cabinet so as to stop the troika, the creditors and the media from targeting me. He asked me who I thought should replace me at the finance ministry. He had clearly decided who it would be already, but I decided to play along, suggesting the person who I was certain had agreed to take over from me already: my good mate Euclid. I even offered to try to convince Euclid to accept. (And when I did, Euclid pretended he needed to think about it.)

“I would like to ask you to take over the Economy Ministry, so as to team up again with Euclid,” Alexis said.

“What about Stathakis?” I asked.

“I will be happy not to see him in front of me again. Let him vanquish at the backbenches.”

“No, Alexi, I am not interested.” I told him. “You met me because I turned Greece’s debt into the dragon to be slain, and because of my proposals for how to slay it. I live, breathe, think and dream of debt restructuring, of a reduction in surplus targets, an end to austerity, tax rate reductions and the redistribution of wealth and income. Nothing else interests me. To assume the Economy Ministry to manage the EU’s structural fund handouts, just so as to remain minister, is not something I care for. Do you recall why I moved from America? Because you asked me to help you to liberate Greece financially. I ran for Parliament not because I was dying to be an MP but because I did not want to be a technocrat, an unelected finance minister. I thought that that way I would be more useful to the cause. Now, given your abandonment of that cause, I have no reason to be minister. It’s OK. Let someone else do it. I shall be in Parliament where I will help to the best of my ability.”

“You can have some other ministry – maybe Culture, which you and Danae know so much about?” he said laughing. “In any case, there will be many positions in the future from which you can help.”

“You are again confusing me with someone who cares about positions, Alexi. There is only one thing I care about and you know what it is!”

“Let’s sleep on it, let’s think about it.”

“There is nothing to think about,” I said. “There is no time. You have a lot to do.”

When I saw Danae afterwards, she asked me what had happened. “Tonight we had the curious phenomenon of a government overthrowing its people,” I mused.

Minister no more

Back at the flat, I narrated my discussion with Alexis for Danae and her camera and slept for a couple of hours before writing my seventh, and final, resignation letter. After proofreading it a few times, I posted it on my blog under the title ‘Minister No More’. It was one of the hardest pieces of prose I had ever had to compose.

On the one hand, I had a duty to warn the people, our democracy’s demos, that their mandate was about to be trashed. On the other hand, I felt an obligation to preserve whatever progressive momentum there was within our government and within Syriza. At that stage I still believed strongly that comrades like Euclid, with clout in the party that I lacked, would not sign up to the surrender document Alexis and Dragasakis were preparing. Losing a second finance minister in a month or two, if Euclid refused to become complicit in another harsh and hopeless bailout, might cause a rupture within the government and the party. This in turn might lead to new elections, which might further undermine the chances of our honouring the wishes of the 61.3%. I needed to signal both a defiant commitment to the NO vote but also to issue a call for unity. The result was the following text:

Like all struggles for democratic rights, so too this historic rejection of the Eurogroup’s 25th June ultimatum comes with a large price tag attached. It is, therefore, essential that the great capital bestowed upon our government by the splendid NO vote be invested immediately into a YES to a proper resolution – to an agreement that involves debt restructuring, less austerity, redistribution in favour of the needy, and real reforms.

Soon after the announcement of the referendum results, I was made aware of a certain preference by some Eurogroup participants, and assorted ‘partners’, for my… ‘absence’ from its meetings; an idea that the Prime Minister judged to be potentially helpful to him in reaching an agreement. For this reason I am leaving the Ministry of Finance today.

I consider it my duty to help Alexis Tsipras exploit, as he sees fit, the capital that the Greek people granted us through yesterday’s referendum.

And I shall wear the creditors’ loathing with pride.

We of the Left know how to act collectively with no care for the privileges of office. I shall support fully Prime Minister Tsipras, the new Minister of Finance, and our government.

The superhuman effort to honour the brave people of Greece, and the famous NO that they granted to democrats the world over, is just beginning.

With hindsight, I should have sounded a much louder alarm bell regarding Alexis’ intentions. That I did not reflects my misplaced trust in many people in our government, Euclid primarily, to carry out the task of preventing a recapitulation of the Samaras’ government. But I am not sure that a clearer warning would have made much difference. Everyone I have spoken to since that morning understood very well what had happened the moment they heard I had resigned on the night of our triumph.=

Thankfully, as well as the creditors and their groupies, there was one other person who was unconditionally happy at my decision. Daughter Xenia, who had come from Australia to see me two weeks before but had hardly laid eyes on me, upon hearing the news that I had resigned gave me a sleepy, early morning look and said: “Thank goodness, dad. What took you so long?”

———–

[i] My mother, Eleni Tsaggaraki-Varoufaki, served as a local councillor and Deputy Mayor for the Palaio Phaliro Municipality for twenty years or so. She had, indeed, been responsible for the management of local facilities, including orphanages, that were converted into decent shelters for people young and old.

[ii] 62.5% is very high a turnout given that no postal or remote voting is permitted.

[iii] His precise words were so offensive that I do not wish to reproduce them here.

[iv] The executed men were held responsible for the rout of the Greek army and the sacking of all ethnic Greek cities, villages and communities by the army of Kemal Ataturk and Turkish irregulars, eradicating all Greeks from Asia Minor where they had lived since Homer’s time. Hundreds of thousands died and even more flooded mainland Greece as refugees. A coup d’état ensued in Greece and a military tribunal was convened at which the political and military leaders of the disastrous campaign were found guilty of high treason.