Executive summary: if investments are needed, do not reform. Invest. Investments are the reform. Angus Maddison (historical patterns of growth) and Jan Kregel (leading post-Keynesian economist) were the intellectually dominant forces during my economics study in Groningen around 1982. Let´s apply their frameworks to Greece. Growth, as we measure it, has many sources: increasing the productivity of existing activities (the mechanization of the potato harvest), shifting labour from low-productivity activities to high-productivity activities (supermarkets outcompeting small groceries), or using less stuff to produce more stuff (the increasing fuel efficiency of planes). One source of productivity increases is, or used to be, old people who retire and end low-productivity businesses

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: business, Economics, economy, Finance, Greece, investments, long run, productivity, Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Schuldenbremse bye bye

Lars Pålsson Syll writes What’s wrong with economics — a primer

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Executive summary: if investments are needed, do not reform. Invest. Investments are the reform.

Angus Maddison (historical patterns of growth) and Jan Kregel (leading post-Keynesian economist) were the intellectually dominant forces during my economics study in Groningen around 1982. Let´s apply their frameworks to Greece.

- Growth, as we measure it, has many sources: increasing the productivity of existing activities (the mechanization of the potato harvest), shifting labour from low-productivity activities to high-productivity activities (supermarkets outcompeting small groceries), or using less stuff to produce more stuff (the increasing fuel efficiency of planes). One source of productivity increases is, or used to be, old people who retire and end low-productivity businesses like small-scale farming or a mom-and-pop store. More complicated: a shift of relative prices (lower prices of imported energy increases nominal domestic value-added, which we, to calculate growth, divide by the price level, which is actually going down because of lower energy prices). Productivity increases real production (the opposite happens in the exporting country). Behind this is the idea that everything happens: productivity increases, and we can make more with less. This applies to the non-money economy, too. Washing machines drove out paid maids. Domestic chores require less labour. But events in Greece are of a different order.

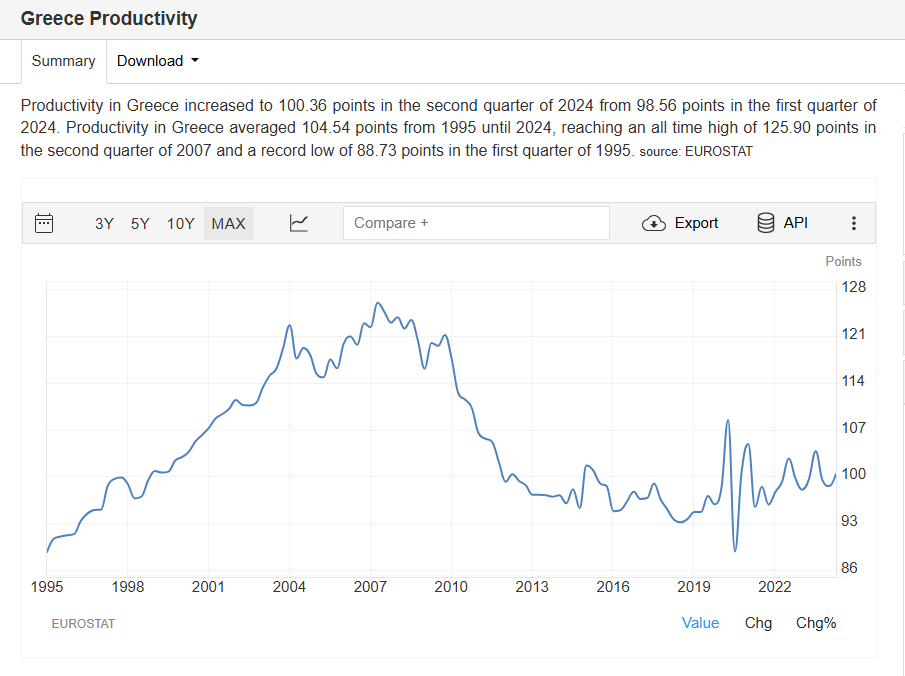

In some countries, productivity has stagnated for quite some time (in Italy since 2001, in the UK and Japan since the Great Financial Crisis in 2009). This is, using a Maddisonian perspective, highly remarkable as productivity has been on a relentless increase since about 1820. Wars? Diseases? Economic crises? Productivity increased or, in case of temporary setbacks, rebounced fast. The decades of stagnation we see are hard to explain, as neither the UK nor (the south of) Italy were highly productive areas. But what happened in Greece is something else. Productivity suddenly decreased by 20% and did not recover despite an (from a European perspective), on average, a low level of productivity.

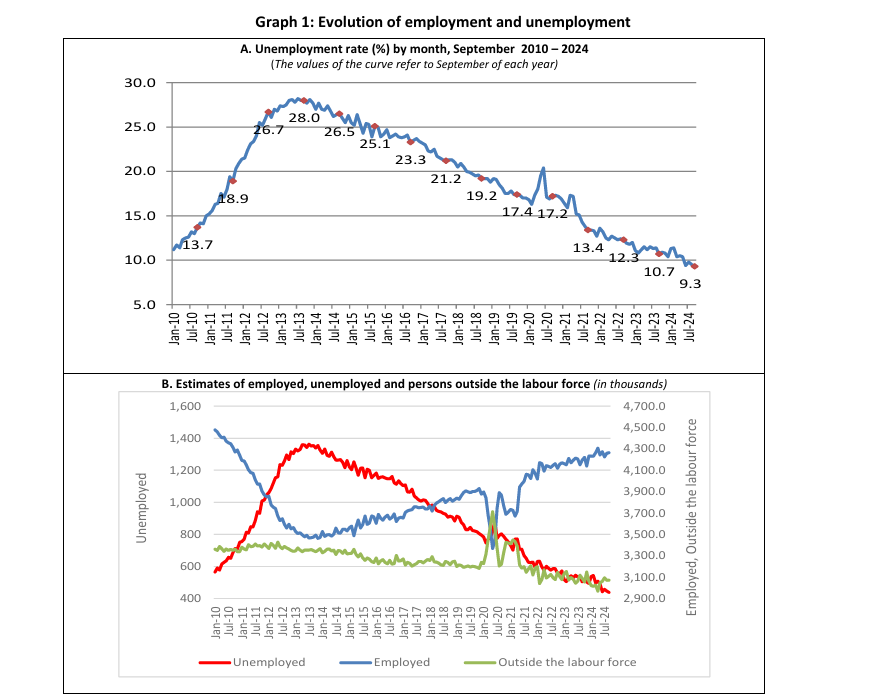

What we do see in Greece, is employment growth. Employment is up, unemployment is down (source).

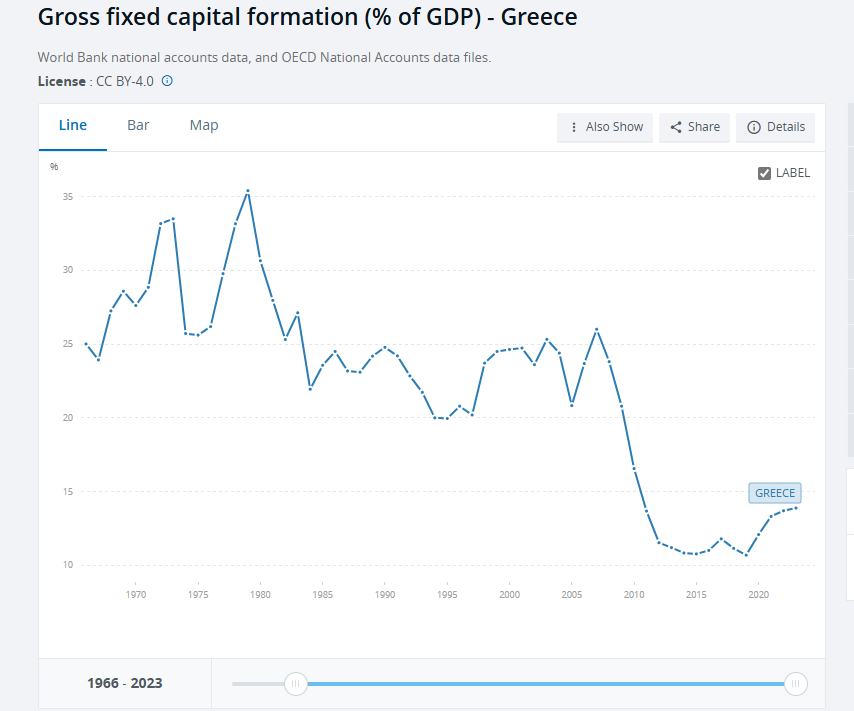

This means that new jobs do not contribute to productivity (on average). Economists in Greece complain that the rate of investment is too low. They are right. Gross fixed capital formation as a percentage of GDP is back to pre-industrial levels.

2. Comes in professor Jan Kregel. The answer to Greece’s plight is simple: Invest. Stop (but that´s what all of Europe should do) creating money to finance mortgages, which only indebt people and jack up the prices of existing homes. Start creating money to invest and grab the future. Solar and desalination of seawater are a match made in heaven (sorry, China). Greece is not short on seawater and sun. Don´t hesitate; don´t try to lure private investors. Invest! We have an entire European Central Bank that could have this as its mandate!