Ladies and Gentlemen, my heartfelt thanks for your presence here tonight. Thanks also to the good people at South Bank who honoured me with the humbling idea and invitation to combine my own musings on globalisation with the remarkable images of Andreas Gursky – images which have, over the years, done so much to enlighten us regarding the topsy-turvy world that we have been helping bring about. Yes, a picture is a thousand words but, at the same time, words liberate our mind’s eye so that it can make sense of otherwise incomprehensible images. Globalisation is such a word – a word packed with humanity’s past aspirations and our current trials and tribulations. Words and images, images and words, must become

Topics:

Yanis Varoufakis considers the following as important: Arts, culture, DiEM25, English, Essays, Political, Politics and Economics, Talks, The Global Minotaur: A theory of the Global Crisis, Theatre, Video

This could be interesting, too:

Chris Blattman writes Top 10 family board games we discovered during the pandemic

Chris Blattman writes Top 10 family board games we discovered during the pandemic

Sergio Cesaratto writes ESC Live! – “Dentro la MMT”

Jeff Mosenkis (IPA) writes IPA’s weekly links

Ladies and Gentlemen, my heartfelt thanks for your presence here tonight. Thanks also to the good people at South Bank who honoured me with the humbling idea and invitation to combine my own musings on globalisation with the remarkable images of Andreas Gursky – images which have, over the years, done so much to enlighten us regarding the topsy-turvy world that we have been helping bring about. Yes, a picture is a thousand words but, at the same time, words liberate our mind’s eye so that it can make sense of otherwise incomprehensible images. Globalisation is such a word – a word packed with humanity’s past aspirations and our current trials and tribulations. Words and images, images and words, must become co-conspirators in our rebellion against the Unholy Alliance of Banality, Oppression and Ignorance. Tonight I shall attempt such a rebellion, blending my words with Gursky’s images.

Ladies and gentlemen, there is bad news; there is worse news; and there is hope. The bad news is that globalisation has triumphed. The worse news is that it is in retreat – albeit not in ways that those of us who opposed its triumphant march can celebrate. And finally there is hope – hope that there is an alternative to both globalisation’s destructiveness and to the parochialism that is now trumping globalisation’s oeuvre in Trump’s America, in Brexit Britain, indeed everywhere.

And the name of this hope? Of the potential scourge of both globalisation and its xenophobic nemesis? Its name is… internationalism – an old friend from a bygone era that fell by the wayside as the Left collapsed into a pile in the late 1980s, weighed down by our own folly. It was that stupendous defeat that allowed the idea of a borderless, cosmopolitan world to be replaced by the dystopic vision of a planet in which digital money and containers stuffed with our artefacts move unimpeded and at incredible speeds while, at the very same time, people are fenced in – surrounded by a new type of impenetrable, brutal, unyielding, murderous wall.

Globalised capital’s triumph, and the fizzling out of the anti-globalisation movement, was perhaps epitomised by the manner in which the establishment succeeded in demonstrating the irrelevance of our polulous global demonstrations against invading Iraq – by invading… Iraq! And by subsequently silencing all opposition to their madness.

Fifteen years later, the globalising capitalist order is getting its comeuppance. And it does so in a manner reflecting a universal irony: It is falling prey to its own oeuvre – to globalising capital’s own, unique capacity to undermine itself – bringing to mind the inimitable lines from the Communist Manifesto of “…a society that has conjured up such gigantic means of production and of exchange” that it resembles “the sorcerer who is no longer able to control the powers of the nether world whom he has called up by his spells.”

It is a form of universal irony, is it not? The most audacious of globalised capitalist accumulation processes have begat labour saving technological change which now underpins jobless de-globalisation all over the planet. In this reading, Donald Trump is merely symptomatic of robotic and financial technologies infesting a social order unable to make good use of them. Which of course, as always, is a double edged sword; a sword that can cut both ways; either embodying our nightmares or, at long last, fulfilling our humanist dreams.

From where I stand, and this will be my argument tonight, only an ambitious new internationalism can help reinvigorate the spirit of humanism at a planetary scale.

Humanity has been globalising ever since our ancestors left Africa, the earliest economic migrants on record. This process was supercharged by capitalism. To quote again from the Communist Manifesto, using its “heavy artillery” – the “cheap prices of commodities” – it has been battering “down all Chinese walls”, “constantly expanding market for its products”, leading to the extraordinary substitution of “…intercourse in every direction, universal interdependence of nations” for “the old local and national seclusion and self-sufficiency.”

None of this is new. So, why did the need for a term like ‘globalisation’ not arise until 1991? The answer is that, around 1991, something genuinely new happened: A world capitalist economic system emerged whose growth and stability relied on increasingly unbalanced trade and money movements – a deliciously contradictory system we have come to know as globalisation – a system that eventually yielded our generation’s 1929 moment in 2008 before, very recently, going into retreat that spawned new forms of parochialism and xenophobia.

But let’s take a closer look at the origins and incongruities of this remarkable species of global economy: of a fully financialised, globalising, capitalism that could only remain stable as long as it was growing increasingly imbalanced. Contradictions have never come more turbocharged than this!

Let’s begin at the beginning: In 1944, as the war was ending, the New Deal administration in Washington understood that the only way to avoid the Great Depression’s return was to ensure that foreigners (Europeans and the Japanese to be precise) would be buying the new washing machines, cars, television sets and passenger jets that American industry would switch to once it ceased producing military hardware for the war effort. But how could the devastated Europeans and Japanese afford American goodies? The only way was to transfer to them a portion of American economic surpluses. A form of ingenious surplus or wealth recycling was instituted. Its purpose was not philanthropy but a penchant to generate foreign demand for American net exports. The Marshall Plan was but one example of this.

Thus began the project of dollarising Europe, of founding the European Union as a cartel of heavy industry, and of building up Japan within the context of a global currency union based on the American dollar. This new system, also known as the Bretton Woods system, succeeded in equilibrating a global system featuring fixed exchange rates, almost constant interest rates, and… boring banks operating under severe restrictions. It was a dazzling design that brought us capitalism’s golden age of low unemployment and inflation, high growth, and impressively diminished inequality.

Alas, by the late 1960s it was dead in the water. Why? Because the United States lost its surpluses and slipped into a burgeoning trade deficit and an enormous federal budget deficit, rendering America no longer able to stabilise the global system it had fashioned. Never too slow to confront reality, Washington killed off its finest creation: On 15th August 1971 President Richard Nixon announced the ejection of Europe and Japan from the dollar zone. Unnoticed by almost everyone, what we now call globalisation was born on that summer day.

Nixon’s decision was founded on the refreshing lack of deficit-phobia that is typical of American policy-makers. He was simply unwilling to rein in deficits by imposing austerity. Why? Because austerity would have done more to shrink the America’s capacity to project hegemonic power around the world than to shrink its deficits. So, instead, Washington counter-intuitively stepped on the accelerator to boost those deficits! The result was that the United States functioned like a giant vacuum cleaner, sucking in massive net exports from Germany, Japan and, later, China.

- SALERNO 1991

However, what gave that era (1980-2008) its energy and character was the manner in which America paid for these expanding deficits: by means of a tsunami of other people’s money – European, Japanese and later Chinese net exporters’ profits rushing into Wall Street in search of higher returns.

But for Wall Street bankers to act as this magnet of other people’s capital, Wall Street had to be unshackled from its New Deal and Bretton Woods era fetters. Bank de-regulation was part of a Faustian bargain: The bankers would syphon into America European and Asian profits to cover America’s trade and government deficits. And the American government would allow them to go berserk. That was the social contract, the Faustian bargain, behind globalisation.

There was also a second condition for Europe’s and Asia’s capital to want to flow into America: the cheapening of American labour that was essential to push Wall Street’s capital returns above those of Frankfurt and Tokyo, where competitiveness was based instead on enhancements to productivity.

- FRANKFURT 2007

- TOKYO 1990

But how could Americans continue to buy other people’s stuff when their wages shrunk? With escalating credit, provided by Wall Street, is the answer. You may recognise a similar history here in Britain, ladies and gentlemen. The United Kingdom, having de-industrialised under Mrs Thatcher, bet the house on attaching the City to Wall Street and turning the British economy into a simulacrum of America, without of course the capacity to regulate globalised capitalism: Private debt, financialised houses and the City became the only shows in this town, in London, the only town that matters to this country’s economic oligarchy.

Every new regime needs its own ideology, its religion. Neoliberalism was rescued from the loony fringes of political economics to play that role in the 1970s. It had as much to do with really existing capitalism as Marxism had to do with Brezhnev’s Soviet Union: Nothing whatsoever! Neoliberal economists were never central in policy making. But they did provide the sermons that steadied the hand of politicians repealing New Deal era protections for workers and society at large from the motivated abuses of Wall Street bankers and predators such as Wal-Mart who turned cheapened goods and cheapened labour into the West’s new mantra.

Before long, the Soviet Union and its satellites collapsed. In Eastern Europe, the new-old rulers were keen for a piece of the action. Meanwhile, in Beijing, the Chinese Communist Party was determined to survive by staging a managed insertion of China’s workers into capitalism’s proletariat. Financial capital’s inexorable march and two billion workers entering the global labour market ensured a spectacular redistribution of income and wealth.

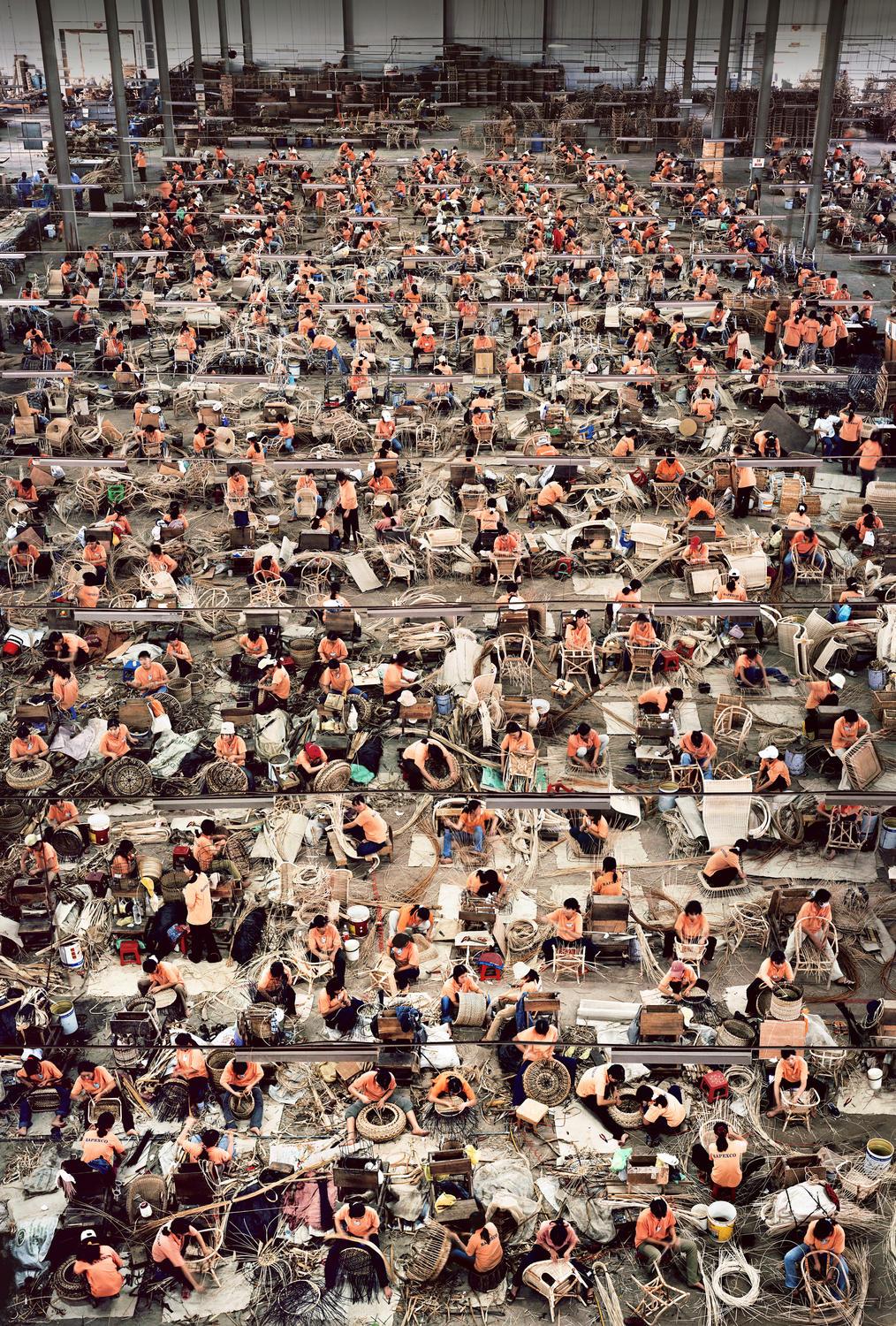

- NHO TRANG 2004

While billions of people were lifted from abject poverty in Asia, large numbers of Western workers were discarded, their voices drowned out by the cacophony of money-making in financialisation’s epicentres.

We now all lived in a global village, we were told. History had ended. The success or failure of each one of us, of our community, our nation now depended entirely on how cheap we and our products had become. It was a compelling narrative. Distances were shrinking through digitisation, supply chains lengthened hugely, global intercourse was exciting and it was revolutionary. Our May Day events, …

- MAYDAY

…anti-globalisation gatherings, the World Social Forum – they all seemed out of place – the reactions of recalcitrants who refused to accept that we lived in a brave new paradigm.

BUT, one reality refused to concur with the global village narrative. A wall. Not a new wall. But one made up of many older walls that began to unite, to globalise, as if in order to expose globalisation for what it truly was: a process of deepening divisions, of dangerous imbalances, of a shocking disequilibrium presenting itself as harmony, as congruence, as… equilibrium.

The seeds of the wall I am talking about were sown in the Balkans, under the Nazi occupation, in Yugoslavia and in Greece. The harvest began in the streets of my hometown, Athens, in December 1944; yielding a Civil War of an awfulness and global significance that went almost wholly unnoticed. The world began to pay attention:

- when, from the streets of Athens in December 1944, it moved to Berlin, which it partitioned in the following June

- when it produced two Koreas in that August

- leapfrogged to the mountain ranges of Kashmir exactly two years later, on 15th August 1947, as the new fledgling nations of the subcontinent, instead of celebrating independence, clashed

- when it flared up in 1948 in the guise of ethnic cleansing and in the midst of all-out-war in Palestine

- when it made its mark in the streets of Nicosia with a green line, drawn innocuously by a British general in 1956, before returning in the form of barricades in 1963, two years after the similar soft division in Berlin was transformed, within four short days, into the Wall’s most famed incarnation.

When the Troubles broke out in Belfast, and Sunday 30th January 1972 was indelibly bloodied by the British Army, it was there to embellish the pre-existing discontent with euphemistically called Peace Walls. Two years later, in 1974, the barricades along Nicosia’s Green Line, as if in a bid not to be outdone by Berlin or Belfast, grew also into a fully-fledged wall.

Then, in 1989, while the Berlin Wall was falling, and the world was turning, supposedly, into our Global Playground, something remarkable happened: Instead of these walls disappearing, they divided, multiplied and grew stronger, uglier. They invaded disintegrating Yugoslavia, stood tall in the midst of hitherto unified communities in Africa’s Horn, where they claimed grey zones from the rugged tablelands between Ethiopia and Eritrea, and grew more insidious in Palestine, the US-Mexico border, in the streets of Bagdad, in Georgia, in the Ukraine, in our own cities, their shopping malls and gated pseudo-communities; the list goes on.

In 2005, my partner, artist Danae Stratou, announced that her next installation would consist of pairs of photographs, one for each of seven harsh divisions from around the world. She would stand right on the division, in Palestine, in Kashmir, on the US-Mexico border… photograph each side… print the photos in large transparencies and then construct a corridor that the viewer would walk through made of these seven pairs of large hanging photographs – as if walking on a division line taking the viewer from Cyprus to Palestine to Kasmir to the beach dividing San Diego on the one side and Tijuana on the other – a path meant, potentially, to unify, to heal, the division.

For a year we travelled together to these divisions which globalisation, theoretically, was making obsolete but, in practice, it was reinforcing. During those travels a Great Paradox hit me: The more globalisation was meant to develop reasons for dismantling the dividing lines, the less powerful the forces working to dismantle them were proving. Deepening divisions, patrolled by increasingly merciless guards, appeared to us the homage that globalisation was paying to organised misanthropy.

During our travels, our faces pushed up against those hideous fences, the reality of globalisation hit me more powerfully than ever. Here is something that I put down in my diary in March 2006, in Juarez – a stone’s throw from El Paso:

“It is not just that the walls are getting stronger, rather than more brittle. It is also that they are globalising. The reason is, I think, because the importance of deep divisions for stabilising a grossly unstable world order is growing by the day. The raison d’ être is the same. It affects different Walls in similar ways. They start resembling each other. Both in terms of the social forces that huddle in their shadow but also physically. Aesthetically. A Mitrovica Serb would feel more at home in Nicosia than in Belgrade. An Eritrean residing in Tsorona will feel a sense of familiarity, despite the intense cold, near the Line of Control in alpine Kashmir than she would in Asmara. An Ulster unionist will have no trouble coming to grips with the reality of the ghost city of Famagusta, in Cyprus, whereas he may well feel a stranger in London. A Palestinian from Qalqilia will discover strange bonds with a resident of Juarez; bonds that she may not feel in Cairo. The mere fact that Israeli engineering teams have been employed by the US government to help transplant Sharon’s Wall to California, New Mexico, Arizona and Texas speaks volumes.”

After our travels, Danae completed and exhibited her installation, entitled ‘CUT – 7 dividing lines’. Soon after, based on these scribblings of mine and the idea that the divisions were but a single wall that was globalising – the nasty underbelly of the fictitious Global Village – she put together a video that featured as part of another installation entitled ‘The Globalising Wall’. Here it is, with a soundtrack comprising actual recordings Danae made in situ plus string music by Ada Pitsou.

That was in 2006. Two years before globalisation was to be mortally wounded by our generation’s 1929. John Maynard Keynes once wrote: “Speculators may do no harm as bubbles on a steady stream of enterprise. But the position is serious when enterprise becomes the bubble on a whirlpool of speculation.” Which is precisely what had happened by 2007: On the whirlpool of the tsunami of European and Asian profits rushing into Wall Street, bankers built oversized bubbles of exotic forms of private debt which, at some point, had surreptitiously acquired the properties of private money.

When these bubbles burst in 2008, the recycling loop maintaining globalisation was broken despite energetic money printing by central banks and the Chinese authorities’ breath-taking credit and investment spree. American deficits, even after they returned to their pre-2007 levels, could no longer stabilise globalisation. The reason? Socialist largesse for the few and ruthless market forces for the many damaged aggregate demand, repressed the entrepreneurs’ sales expectations, restricted investment in high quality jobs, diminished earnings for the many and, surprise-surprise, confirmed the entrepreneurs’ pessimism that underpinned low investment and low demand. Adding more liquidity to that mix made not a scintilla of a difference as the problem was not a dearth of liquidity but a dearth of demand.

Wall Street, Wal Mart and Walled citizens. Those were globalisation’s symbolic foundations. Today, all three have become a drag on globalisation:

- Banks are failing to maintain the capital movements that globalisation used to reply upon, as total financial movements across the globe are less than one fourth of what they were in early 2007.

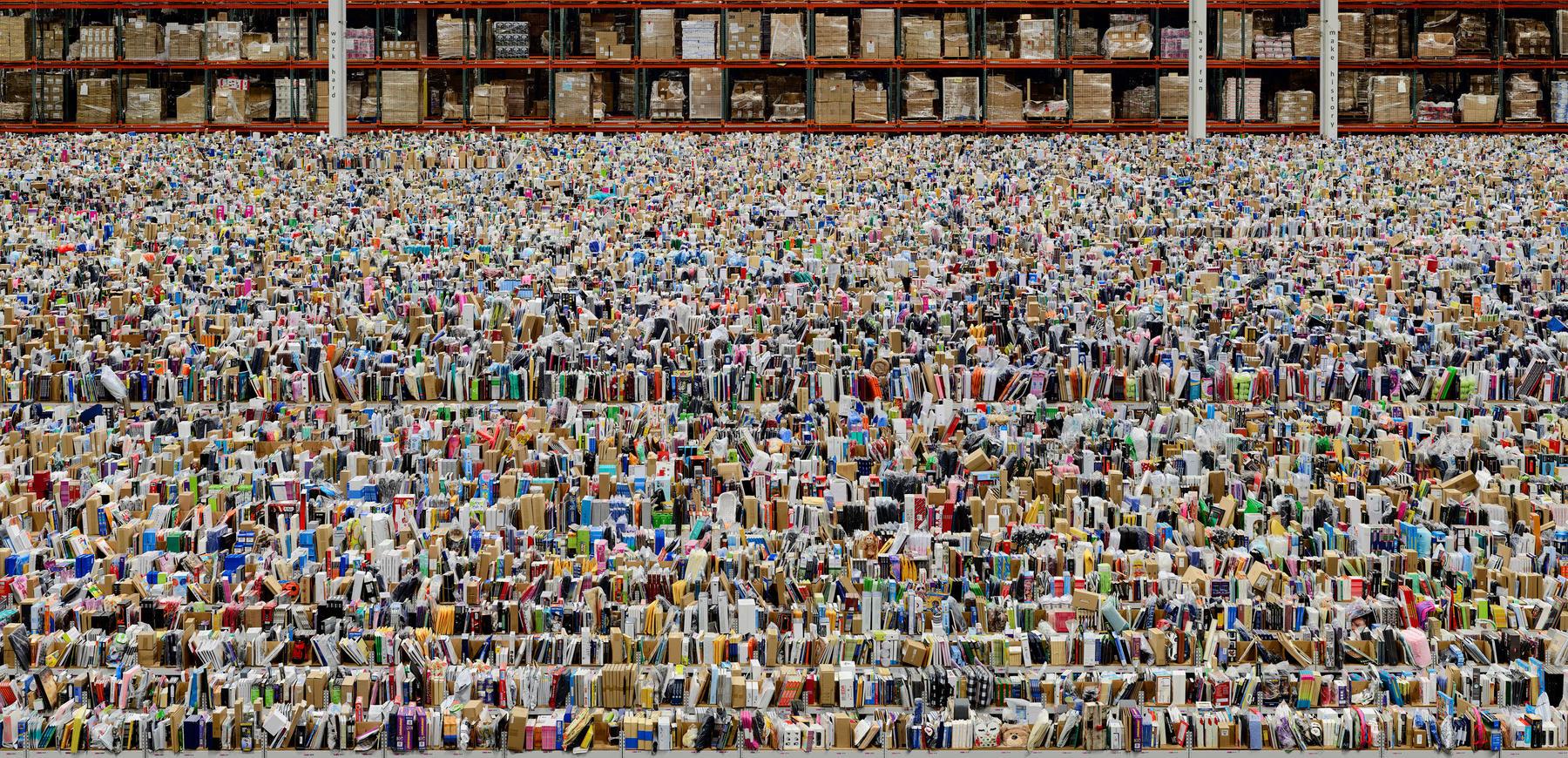

- Wal Mart, whose ideology of cheapness symbolised the devaluation of labour and the gutting of traditional local businesses, is itself squeezed by the Amazon model whose ultimate effect is a further shrinking of overall spending.

- And the walls that were the nasty underbelly of the ‘global village’ – the US-Mexico border; the European Union’s contemptible policy of strategically using the Mediterranean as a watery tomb for tens if not hundreds of thousands – our Globalising Wall is in the news more than ever before and a source of political discontent, illegitimacy, misanthropy.

- AMAZON

Looking at the world from an Archimedean distance, globalization has been caught in a steel trap of its making. Let me put it bluntly: Its crisis is due to too much money in the wrong hands. Humanity’s accumulated savings per capita are at the highest level in history. However, our investment levels (especially in the things that humanity needs, like green energy) are, in comparison, at an all-time low.

In the United States, massive sums are accumulating in the accounts of companies and persons that have no use for them; while those without prospects or good jobs are immersed in mountains of debt. In China, savings approaching half of all income sit side-by-side with the largest credit bubble imaginable. Europe is even worse: There are countries with gigantic trade surpluses but nowhere to invest them domestically (e.g. Germany and the Netherlands); countries with deficits and no capacity to invest in badly needed labour and capital (e.g. Italy, Spain, Greece); and, to boot, a European Union unable to mediate between the two types of countries due to the lack of federal-like institutions that could do this.

And as if these discontents were not enough, there is also the rise of the machines. Almost half of the professions in Europe and North America will be susceptible to automation by 2020. Robots require few, highly paid, designers and operators but may replace millions. This generates labour shortages and labour gluts in the same city, at the same time. Western middle classes are in for another hollowing out, wage inequality is about to rise again in the richer countries, while developing countries will soon realize that having large young populations offers no respite from poverty: With robots getting smarter and cheaper, de-globalisation takes over and countries like Nigeria, the Philippines and South Africa will bear the brunt of re-localisation – especially so given the evolution of 3D printing.

Is it any wonder that, in view of globalisation’s secular crisis, parochialism, nativism and xenophobia are rearing their ugly head everywhere? Rather than focusing on the role of Facebook, Vladimir Putin or some unexplained new-fangled fear of the ‘foreigner’, the so-called liberal establishment (which by the way is neither liberal nor particularly well established – judging by recent electoral results in Europe and in America) should look instead at globalisation’s rotting foundations.

Watching globalisation’s liberal cheerleaders fret as trade is regionalised, capital flows drop off, and production is re-localised, reminds this left-winger of the denial in the faces of quite a few of my comrades as ‘really existing’ socialism was crumpling all around us in 1991. “But globalisation lifted billions from poverty!”, they squeal just as my comrades were squealing, equally correctly, that the Soviet Union had propelled a nation from the plough to Sputnik in a decade. So what? A system that is unsustainable will not be sustained.

- Review 2016

If globalisation is no longer viable, what next? The answer offered by the alt-right, the xenophobes, and those who invest in militant parochialism is clear: return to the bosom of the nation-state, surround your selves with electrified fences, and cut deals between the newly walled realms on the basis of national interest and relative brute strength. The fact that this nightmare is presented as a dream is yet another failure of globalisation, just like Donald Trump was a symptom of Barrack Obama’s failure to live up to the expectations he had cultivated amongst the victims of globalisation and its 2008 spasm.

Lest we forget, our problems, are global. Like climate change they demand local action but, also, a level of international cooperation not seen since Bretton Woods. Neither North America nor Europe or China can solve them in isolation or even via trade deals. Nothing short of a progressive, new Bretton Woods can deal with tax injustice, the dearth of good quality jobs, wage stagnation, public debt, personal debt, low investment in things humanity desperately needs, too much spending on things that are bad for us, increasing depravity in a world awash with cash, robots that are marginalising an increasing section of our workforces, prohibitively expensive education that the many need to compete with the robots etc. National solutions, to be implemented under the deception of “getting our country back” and behind strengthened border fences, are bound to yield further discontent as they enable our oligarchs-without-borders to strike trade agreements that confine the many to a race-to-the-bottom while securing their loot in offshore havens.

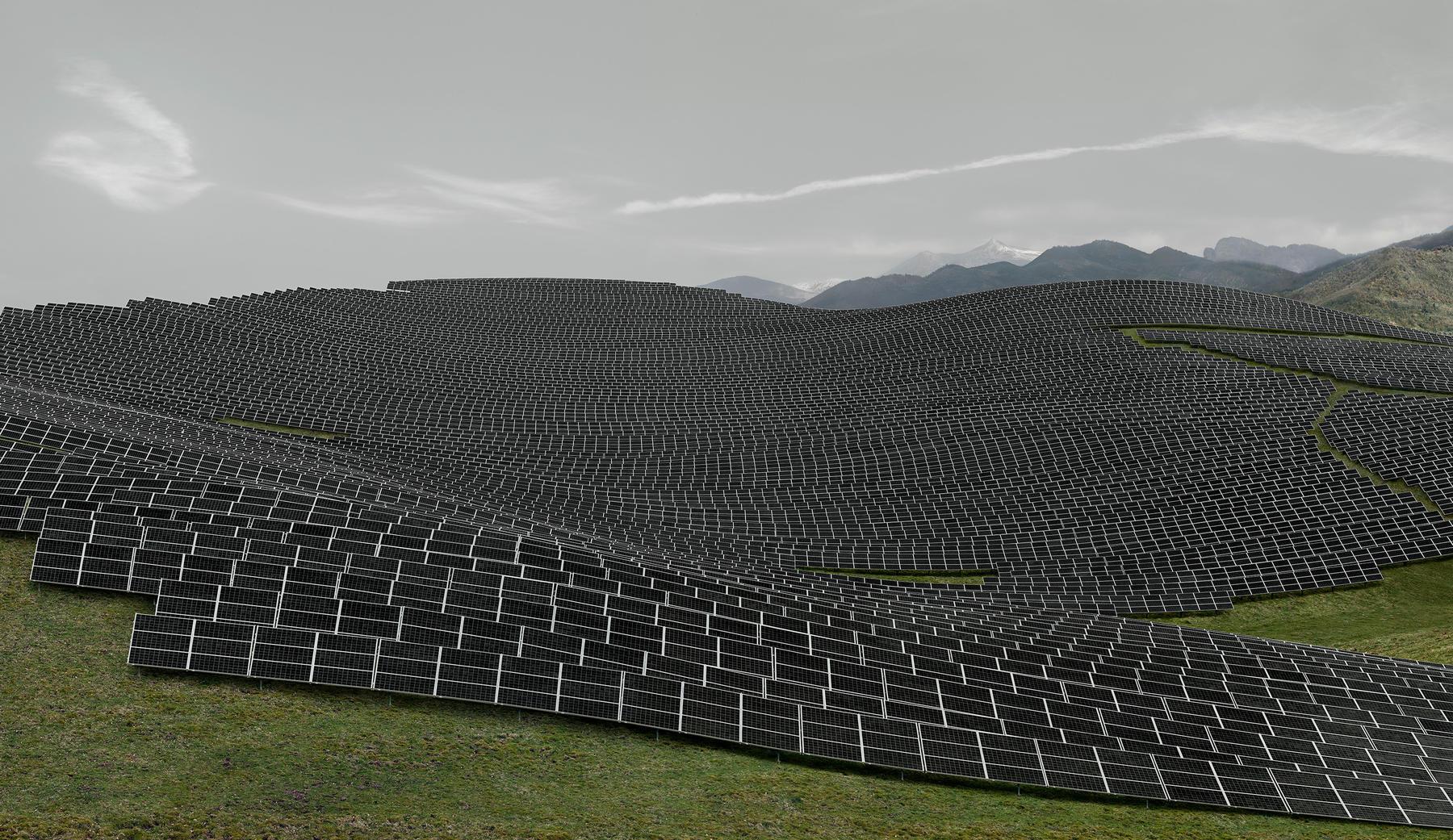

Our solutions, therefore, must be global too. But to be so they must undermine at once parochialism and globalisation, both the right of capital to move about unimpeded and the fences that stop people and commodities from moving about the planet. In short, our solutions must be internationalist: Tax havens are crying out for international harmonisation. Climate change demands common environmental standards and a green energy union that should be democratically governed lest we end up with new monstrosities.

- LES MEES 2016

Free trade must be combined with standards that enhance human happiness everywhere. The financial genie needs to be put back in its bottle with capital controls domestically and globally to be imposed by coordinated action in the Americas, in Europe, in Asia. Money must be democratised and be managed internationally in a manner that eliminates systematic trade deficits and systematic trade surpluses. The robots must become humanity’s slaves (so that the opposite does not obtain), a feat that ultimately requires their common ownership.

All this sounds utopian. But not more so than the idea that the globalisation of the 1990s can be maintained in the 21st century, or be replaced profitably for the majority by a revived nationalism. At historic junctures like the present, humanity is usually faced by a dilemma between an inexact utopia and a certain dystopia. The trick is to opt for the former, realistically, through targeting achievable first goals.

What should these be? Five goals of an International Green New Deal seem pressing and tangible:

(1) Higher wages everywhere, supported by trade agreements predicated upon commonly agreed minimum wages and conditions.

(2) Tax harmonisation, including a simple commitment to deny companies registered in off shore tax havens legal protection of their property rights.

(3) A Green Energy Union focusing on common investment and common standards, with the active support of public investment banks and central banks.

(4) A New Bretton Woods that recalibrates our financial infrastructure, with one umbrella digital currency in which all trade is denominated in a manner that curtails destabilising trade surpluses and deficits.

(5) A universal basic dividend to be administered by the New Bretton Woods institutions and funded by a percentage of big tech shares that are deposited in a World Wealth Fund.

Who should pursue this internationalist agenda? We must!

Progressives from Europe and North America have a duty to start the ball rolling. I have no doubt that, if we embark upon this path, others in Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and Africa will soon join us enthusiastically.

Closer to home, our Democracy in Europe Movement, DiEM25, takes this duty seriously. For example, we shall take this agenda, which we refer to as the European Green New Deal, to voters across Europe in the May 2019 European Parliament elections.

And, just in case you wondered, yes, we plan to campaign in Britain too, even though, sadly, there will be no European Parliament elections here.

Why campaign in Britain? Because Brexit or no Brexit, within or without the single market, British progressives and the rest of us on continental Europe must bind together – because we must not allow Brexit to forge new divisions either across the British Channel or between good, progressive Brits who support Brexit and good, progressive Brits who remain Remainers.

So, yes, we shall campaign in Britain too, alongside Jeremy Corbyn, John McDonnel, Caroline Lucas, progressives in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Starting with our first event next week in Sheffield, we shall campaign as symbolic proof of our commitment to the idea of unity amongst all progressives here, on the Continent, in North and South America, in Africa, everywhere.

With globalisation in retreat, and militant parochialism on the rise, we have a moral and political duty to tackle a failing globalisation with a renewed, ambitious internationalism.

Let us begin with an agenda, as Pink Floyd once called upon us to do, to ‘Take Down The Wall’ – this hideous, globalising wall.

Thank you