By Al Campbell, Ann Davis, David Fields, Paddy Quick, Jared Ragusett and Geoffrey Schneideroriginally posted hereIntroduction Ten years after the financial crisis, we still find mainstream economists engaging in overly simplistic analysis that does not accurately capture the dynamics of the real world. People studying economics need to know that the principles of mainstream economics are hopelessly unrealistic. In this short article, we demonstrate that the ten principles of economics in Gregory Mankiw’s best-selling textbook are divorced from reality and reflect an extreme and unwarranted bias towards unregulated markets.[ii] Mankiw’s “Ten Principles of Economics” should more accurately be titled “Ten Principles of Unrealistic Neoclassical Theory.”Mankiw’s Principle #1:

Topics:

Steve Keen considers the following as important: American Review of Political Economy, Heterodox, Heterodox Economics, Mainstream, mankiw, neoclassical economics, Radical Political Economy, URPE

This could be interesting, too:

Matias Vernengo writes What is heterodox economics?

Matias Vernengo writes Book Presentation “India from Latin America. Peripherisation, Statebuilding, and Demand-Led Growth” by Manuel Gonzalo

Matias Vernengo writes Barkley-Rosser Jr. (1948-2023)

Matias Vernengo writes What is heterodox economics? Some clarifications

By Al Campbell, Ann Davis, David Fields, Paddy Quick, Jared Ragusett and Geoffrey Schneider

originally posted here

Introduction

Ten years after the financial crisis, we still find mainstream

economists engaging in overly simplistic analysis that does not

accurately capture the dynamics of the real world. People studying

economics need to know that the principles of mainstream economics are

hopelessly unrealistic. In this short article, we demonstrate that the

ten principles of economics in Gregory Mankiw’s best-selling textbook

are divorced from reality and reflect an extreme and unwarranted bias

towards unregulated markets.[ii] Mankiw’s “Ten Principles of Economics” should more accurately be titled “Ten Principles of Unrealistic Neoclassical Theory.”

Mankiw’s Principle #1: People Face Tradeoffs/There is no such thing as a free lunch.

Mankiw ignores the historical determination of the distribution of

resources and the crucial distinction between those whose income comes

almost entirely from the performance of labor and those whose income

comes from their ownership of capital. As a result he is unable to

recognize the political power that results from the concentration of

wealth in the capitalist class, and to analyze the distributional impact

of decisions in which those who gain are often significantly different

from those who lose. In addition, history is full of accounts of

forcible appropriation of resources that appeared to be “free” to those

who acquired them.

Mankiw’s Principle #2: The Cost of Something Is What You Give Up to Get It/Opportunity Cost

Insofar as individuals are able to make decisions, their choices can

be described as “giving up” one opportunity in order to take up another.

This tells us nothing about the determination of the choices that are

available to them. The “choice” of a worker as to whether to take on a

dangerous job or face eviction from a home requires a very different

analysis than one suitable for a discussion of the choice between apples

and oranges. On a different level, an analysis of the “trade-off”

between income now and increased income in the future requires an

understanding of ecological limits to the growth of material production.

Mankiw’s Principle #3: Rational People Think at the Margin.

Neither consumers nor producers, nor humans in many other social

roles, generally act on the margin. The assertion of marginal analysis

that decisions must be such as to equate marginal benefit with marginal

cost is simply a restatement of the first derivative condition resulting

from maximization subject to a constraint, rather than a reflection of

real human choice. Mainstream theory then defines behavior according to

this mathematical construction even though it does not govern actual

choice in the real world. But more important is the presumption that all

decision-making is guided by the well-being of isolated individuals,

and thus that “rationality” consists of behavior that maximizes the

benefit of the individual decision–maker. This dismisses the fact that

people are social animals whose decision-making recognizes the

interaction between individuals, and it ignores how in the real world

people make decisions considering their whole situation under possible

alternatives, material restraints, imperfect information, their

cognitive abilities, the existing power structures, and culture.

Mankiw’s Principle #4: People Respond to Incentives.

This is tautological. Furthermore, models based on monetary

incentives by selfish, isolated individuals and firms in perfectly

competitive markets are unrealistic and ignore crucial real world

issues. Monetary incentives are not all that matters. In the real world

people make many decisions on the basis of their evaluation of the

resulting well-being of many people beyond themselves, or on social and

cultural norms.

Mankiw’s Principle #5: Trade Can Make Everyone Better Off.

Trade can increase total production, but trade has distributional

impacts, with winners and losers. Trade in modern capitalism tends to

foster inequality while undermining wages and working conditions for

many laborers. This principle promotes unregulated trade, but

unregulated trade has not proven to be the best route to economic

development, nor is it good for all people. In the real world, infant

industries, immiserating growth, terms of trade shocks, and increasing

inequality render this principle useless as a policy guide.

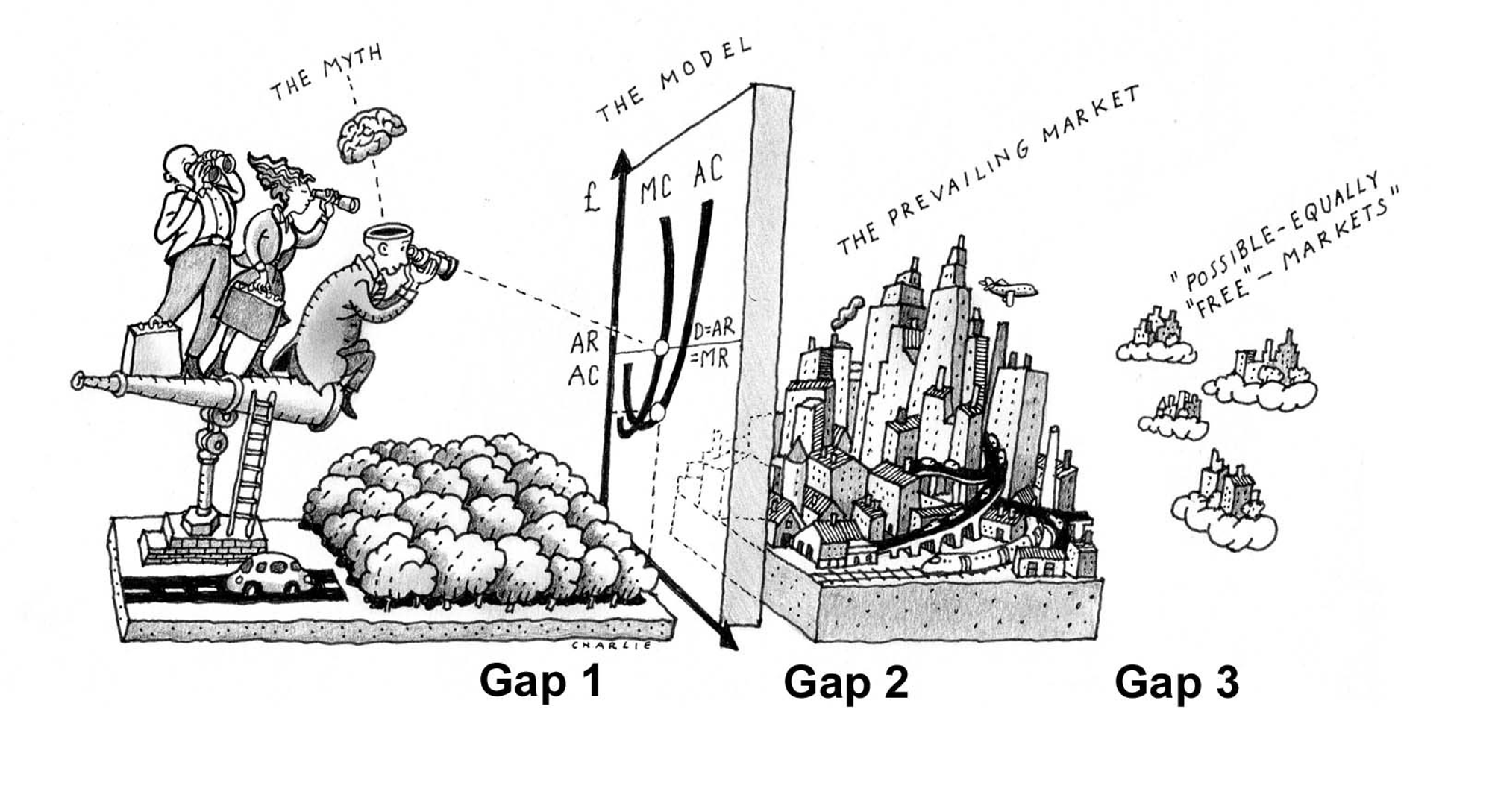

Mankiw’s Principle #6: Markets Are Usually a Good Way to Organize Economic Activity.

As there are no measurable units by which one can classify all

specific economic activities in the real world as “good” or not,

principle #6 is nothing more than a neoclassical ideological declaration

of faith. Markets are human creations that operate differently in

various economic systems, and the various existing and potential

economic systems themselves are human creations. The first real question

then is if under an existing system private capitalist markets driven

by the profit motive do better than possible alternative human creations

for providing the good or service, potentially driven directly by the

desire to meet specific human needs. Important examples providing

evidence of the inferior performance (efficiency and effectivity) of

private capitalist market-driven systems are well run social security

systems and single-payer health care systems. Avoiding the error of

accepting the system as given, a deeper question would be if under some

different economic system, which was not built to favor capitalist

accumulation, alternatives could outperform profit-driven markets

operating in capitalist systems.

Mankiw’s Principle #7: Governments Can Sometimes Improve Market Outcomes.

Behind this assertion is the idea that markets are natural and could

run without any government intervention, and that such natural markets

tend to be efficient but sometimes are not quite optimal. In those cases

the efficiency of markets could be improved by government tweaks. To

the contrary, in the real world all markets are created by governments,

which both establish the rules of the game and enforce them, and thereby

determine market outcomes. If the government passes laws requiring that

food be safe, that changes the market for food, and yields different

market outcomes than if those laws did not exist. With this

understanding, principle #7 is reduced to the not very profound

statement that because governments create markets, they have the ability

to create them with better or worse outcomes. Further, the issue always

ignored by neoclassical economics of social divisions is particularly

important for considering “better market outcomes”: better for whom?

Market rules are shaped by power structures to benefit some classes and

other social groups more favorably than others (for example capitalists

at the expense of workers, First World countries at the expense of Third

World countries, etc.).

Mankiw’s Principle #8: A Country’s Standard of Living Depends on Its Ability to Produce Goods and Services.

Higher GDP per capita does not necessarily result in a higher

material standard of living for all people within, as well as between,

countries. Furthermore, neoclassical economics operates with a

definition of “standard of living” as the amount of goods and services

consumed, so this principle reduces to the not quite tautological, but

not very insightful, claim that the amount of goods and services

consumed in a country depends on its ability to produce them. In the

real world what people are concerned with is their quality of life,

which includes social respect, power to act on one’s desires, conditions

of work (and not just pay), social relations, and much more.

Neoclassical economics does not address the extension of principle #8 to

what people in the real world are actually concerned with, their

quality of life, for which the goods and services produced are just one

among many determinants.

Mankiw’s Principle #9: Prices Rise When the Government Prints Too Much Money.

Since the neoclassical definition of “too much money” is the amount

that makes prices rise, this is a tautology. In the real world the

relationship between prices and the money supply is complex: expanding

money might cause a jump in prices or it might cause no price increases

at all, depending on many other things in the economy. The applied

policy transformation of this into the incorrect claim that “prices rise

when the government prints more money” is an ideological artifice, used

today to justify austerity policies and keeping wages low.

Mankiw’s Principle #10: Society Faces a Short-Run Tradeoff between Inflation & Unemployment.

The relationship between inflation and unemployment is complex and

does not follow a systematic pattern. By the 1970s data from the real

world had caused textbooks to go from Phillips Curves to Shifting

Phillips Curves to abandoning them entirely. In view of that experience,

principle #10 of a short-term trade-off between inflation and

unemployment has become a neoclassical ideological justification for

challenging those who advocate policies that would reduce the rate of

unemployment, by fostering fears of inflation that may never

materialize.

In conclusion, Mankiw’s so-called “Ten Principles of Economics”

ignore crucial realities of the economic world. In particular, Mankiw

excludes power imbalances, inequality, social forces, development

experiences, the realities of market behaviors, laws and outcomes,

realistic measures of quality of life, and recent macroeconomic data

from his principles. It is hard to imagine a less useful set of ideas to

guide modern societies in designing a good economic system.

Unfortunately, almost all other mainstream principles of economics

textbooks parrot these same principles. Students of economics will have

to look elsewhere for useful analysis of the economy and how to build a

democratic economy and society that works for all.

References

Mankiw, Gregory. Principles of Economics, 7th Edition. Stamford, Connecticut: Cengage. 2015.

End-notes

[i]

In a subsequent article, we will offer a set of principles of radical

political economy to provide a more realistic, alternative approach.

[ii]

The authors are members of the steering committee of the Union for

Radical Political Economics (URPE). The ideas presented in this article

are those of the authors and not of URPE. The purpose of this article is

to make readers aware that there are alternatives to the principles of

economics put forth by mainstream economists. We synthesize the

critiques of mainstream economics by radical political economists in

order to give students and teachers ammunition to confront the

unrealistic paradigm of neoclassical economics that currently dominates

the profession.