What’s wrong with Krugman’s economics? Krugman writes: “So how do you do useful economics? In general, what we really do is combine maximization-and-equilibrium as a first cut with a variety of ad hoc modifications reflecting what seem to be empirical regularities about how both individual behavior and markets depart from this idealized case.” But if you ask the New Classical economists, they’ll say, this is exactly what we do—combine maximizing-and-equilibrium with empirical regularities. And they’d go on to say it’s because Krugman’s Keynesian models don’t do this or don’t do enough of it, they are not “useful” for prediction or explanation … The trouble is that the macroeconomic evidence can’t tell us when and where maximization-and-equilibrium goes

Topics:

Lars Pålsson Syll considers the following as important: Economics

This could be interesting, too:

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Schuldenbremse bye bye

Lars Pålsson Syll writes What’s wrong with economics — a primer

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Krigskeynesianismens återkomst

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Finding Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors (student stuff)

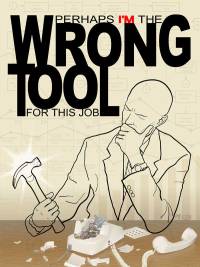

What’s wrong with Krugman’s economics?

Krugman writes: “So how do you do useful economics? In general, what we really do is combine maximization-and-equilibrium as a first cut with a variety of ad hoc modifications reflecting what seem to be empirical regularities about how both individual behavior and markets depart from this idealized case.”

But if you ask the New Classical economists, they’ll say, this is exactly what we do—combine maximizing-and-equilibrium with empirical regularities. And they’d go on to say it’s because Krugman’s Keynesian models don’t do this or don’t do enough of it, they are not “useful” for prediction or explanation …

The trouble is that the macroeconomic evidence can’t tell us when and where maximization-and-equilibrium goes wrong, and there seems no immediate prospect for improving the assumptions of perfect rationality and perfect markets from behavioral economics, neuroeconomics, experimental economics, evolutionary economics, game theory, etc.

But these concessions are all the New Classical economists need to defend themselves against Krugman. After all, he seems to admit there is no alternative to maximization and equilibrium …

One thing that’s missing from Krugman’s treatment of economics is the explicit recognition of what Keynes and before him Frank Knight, emphasized: the persistent presence of enormous uncertainty in the economy …

As Rosenberg notes, Krugman works with a very simple modelling dichotomy — either models are complex or they are simple. For years now, self-proclaimed “proud neoclassicist” Paul Krugman has in endless harpings on the same old IS-LM string told us about the splendour of the Hicksian invention — so, of course, to Krugman simpler models are always preferred.

Krugman has argued that ‘Keynesian’ macroeconomics more than anything else “made economics the model-oriented field it has become.” In Krugman’s eyes, Keynes was a “pretty klutzy modeler,” and it was only thanks to Samuelson’s famous 45-degree diagram and Hicks’s IS-LM that things got into place. Although admitting that economists have a tendency to use ”excessive math” and “equate hard math with quality” he still vehemently defends — and always have — the mathematization of economics:

I’ve seen quite a lot of what economics without math and models looks like — and it’s not good.

But if the math-is-the-message-modelers aren’t able to show that the mechanisms or causes that they isolate and handle in their mathematically formalized macromodels are stable in the sense that they do not change when we ‘export’ them to our ‘target systems,’ those mathematical models do only hold under ceteris paribus conditions and are consequently of limited value to our understandings, explanations and predictions of real economic systems.

But if the math-is-the-message-modelers aren’t able to show that the mechanisms or causes that they isolate and handle in their mathematically formalized macromodels are stable in the sense that they do not change when we ‘export’ them to our ‘target systems,’ those mathematical models do only hold under ceteris paribus conditions and are consequently of limited value to our understandings, explanations and predictions of real economic systems.

For years now, Krugman has criticized mainstream economics for using too much (bad) mathematics and axiomatics in their model-building endeavours. But when it comes to defending his own position on various issues he usually himself ultimately falls back on the same kind of models. In his End This Depression Now — just to take one example — Paul Krugman maintains that although he doesn’t buy “the assumptions about rationality and markets that are embodied in many modern theoretical models, my own included,” he still find them useful “as a way of thinking through some issues carefully.”

When it comes to methodology and assumptions, Krugman obviously has a lot in common with the kind of model-building he otherwise criticizes.

If macroeconomic models — no matter of what ilk — make assumptions, and we know that real people and markets cannot be expected to obey these assumptions, the warrants for supposing that conclusions or hypotheses of causally relevant mechanisms or regularities can be bridged, are obviously non-justifiable.

So let me — respectfully — summarize: A gadget is just a gadget — and brilliantly silly simple models — IS-LM included — do not help us working with the fundamental issues of modern economies any more than brilliantly silly complicated models — calibrated DSGE and RBC models included. And as Rosenberg rightly notices:

When he accepts maximizing and equilibrium as the (only?) way useful economics is done Krugman makes a concession so great it threatens to undercut the rest of his arguments against New Classical economics.