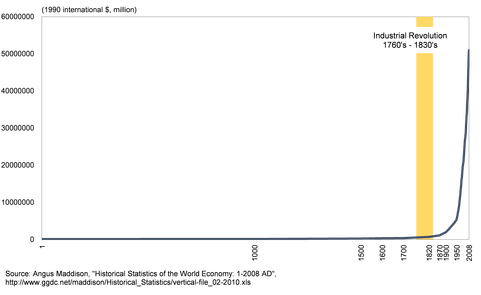

Exhibit 1. Economic growth became norm only after industrial revolution Looking further back in history, however, we can see that economic stagnation due to a lack of borrowers was much closer to the norm for thousands of years before the industrial revolution in the 1760s. As shown in Exhibit 1, economic growth had been negligible for centuries before that. There were probably many who tried to save during this period of essentially zero growth, because human beings have always been worried about an uncertain future. Preparing for old age and the proverbial rainy day is an ingrained aspect of human nature. But if it is only human to save, the centuries-long economic stagnation prior to the industrial revolution must have been due to a lack of borrowers. For the private sector to be borrowing money, it must have a clean balance sheet and promising investment opportunities. After all, private-sector businesses will not borrow unless they are sure they can pay back the debt with interest. But with little or no technological innovation before the industrial revolution, which was essentially a technological revolution, there were few investment projects capable of paying for themselves. Businesses also tend to minimize debt when they see no investment opportunities because the probability of facing bankruptcy is reduced drastically if the firm carries no debt.

Topics:

Editor considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

Exhibit 1. Economic growth became norm only after industrial revolution

Looking further back in history, however, we can see that economic stagnation due to a lack of borrowers was much closer to the norm for thousands of years before the industrial revolution in the 1760s. As shown in Exhibit 1, economic growth had been negligible for centuries before that. There were probably many who tried to save during this period of essentially zero growth, because human beings have always been worried about an uncertain future. Preparing for old age and the proverbial rainy day is an ingrained aspect of human nature. But if it is only human to save, the centuries-long economic stagnation prior to the industrial revolution must have been due to a lack of borrowers.

For the private sector to be borrowing money, it must have a clean balance sheet and promising investment opportunities. After all, private-sector businesses will not borrow unless they are sure they can pay back the debt with interest. But with little or no technological innovation before the industrial revolution, which was essentially a technological revolution, there were few investment projects capable of paying for themselves. Businesses also tend to minimize debt when they see no investment opportunities because the probability of facing bankruptcy is reduced drastically if the firm carries no debt. Given the dearth of investment opportunities prior to the industrial revolution, it is easy to understand why there were so few willing borrowers. Because of this absence of worthwhile investment opportunities, the more people tried to save, the more the economy shrank. The result was a permanent paradox of thrift in which people tried to save but their very actions and intentions kept the national economy in a depressed state. This state of affairs lasted for centuries in both the East and the West.

Powerful rulers sometimes borrowed the funds saved by the private sector and used them to build social infrastructure or monuments. On those occasions, the vicious cycle of the paradox of thrift was suspended because the government injected the saved funds (the initial savings of $100 in the example above) back into the income stream, generating rapid economic growth. But unless the project paid for itself – and politicians are seldom good at selecting investment projects that pay for themselves – the government would at some point get cold feet in the face of a mounting debt load and discontinue its investment. The whole economy would then fall back into the paradox of thrift and stagnate. Consequently, many of these regimes did not last as long as the monuments they created.

Countries also tried to achieve economic growth by expanding their territories, i.e., by acquiring more land, which was the key factor of production in pre-industrial agricultural societies. Indeed, people believed for centuries that territorial expansion was essential for economic growth. This drive for prosperity was the economic rationale for colonialism and imperialism. But both were basically a zero-sum proposition for the global economy as a whole and also resulted in countless wars and deaths.