Over at Bloomberg View, Noah Smith has a pop at what he calls “heterodox economics”. By this he means the new ideas in economic thinking that have sprung up since the 2008 financial crisis but so far haven’t made it into mainstream economic journals.Noah starts by admitting that mainstream economics abjectly failed to predict the crisis and gave little or no guidance on how to deal with it. Because of this, according to Noah, “many people have looked around for an alternative paradigm -- a new way of thinking about macroeconomics that would have allowed us to avoid the pitfalls of the Great Recession.” Indeed they have. Though some of the ideas are not so new – Hyman Minsky’s “Financial Instability Hypothesis”, for example, dates back to 1992. According to Noah, the search for alternative thinking inevitably attracted people who – for whatever reason – “felt shut out” of the mainstream. And as an example of one of these so-called “heterodox” economists, he cites me. Here’s Noah's quotation from my post “The necessary arrogance of elites”, together with his introduction to it: Many among the heterodox would have us believe that their paradigm worked perfectly well in 2008 and after. As an example, take a recent blog post by British economics writer Frances Coppola.

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: Economics, mathematics

This could be interesting, too:

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Schuldenbremse bye bye

Lars Pålsson Syll writes What’s wrong with economics — a primer

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Krigskeynesianismens återkomst

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Finding Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors (student stuff)

Over at Bloomberg View, Noah Smith has a pop at what he calls “heterodox economics”. By this he means the new ideas in economic thinking that have sprung up since the 2008 financial crisis but so far haven’t made it into mainstream economic journals.

Noah starts by admitting that mainstream economics abjectly failed to predict the crisis and gave little or no guidance on how to deal with it. Because of this, according to Noah, “many people have looked around for an alternative paradigm -- a new way of thinking about macroeconomics that would have allowed us to avoid the pitfalls of the Great Recession.”

Indeed they have. Though some of the ideas are not so new – Hyman Minsky’s “Financial Instability Hypothesis”, for example, dates back to 1992.

According to Noah, the search for alternative thinking inevitably

attracted people who – for whatever reason – “felt shut out” of the mainstream.

And as an example of one of these so-called “heterodox” economists, he cites

me. Here’s Noah's quotation from my post “The necessary arrogance of elites”,

together with his introduction to it:

Many among the heterodox would have us believe that their paradigm worked perfectly well in 2008 and after. As an example, take a recent blog post by British economics writer Frances Coppola. Coppola likens mainstream macro to classical music, which walled itself off from the innovations of rock and jazz. Like the musical innovators of the 20th century, she claims, the heterodox have found something that works better than the ossified old ways of the elite:

(The post from which these quotations are taken was actually written in 2012. It was reprinted recently by Evonomics under the title “What UnpopularMusic Can Teach Us About The Future of Economics”.)Heterodox economists working in the real economy –- many of them untrained in formal economics –- not only predicted it but correctly identified the causes …The redefinition of the foundations of economics that is currently being done by heterodox economists will inevitably result in many of the models beloved of academic economists becoming obsolete.

The paragraphs from which Noah has taken these quotations actually

say the exact opposite of what he claims. Here they are, in full:

And as with “serious” music, when economics becomes so divorced from reality that it fails adequately to explain the real world in which people live, people reject it. People rightly ask why academic economists failed either to predict or adequately explain the financial crisis, whereas heterodox economists working in the real economy – many of them untrained in formal economics – not only predicted it but correctly identified the causes. There is a real danger that the anger people feel over what they see as the failure of mainstream economics leads to rejection of mainstream economics in its entirety and, importantly, withdrawal of funding for academic economic research. This, I feel, would be a mistake.

We may not see the relevance of dynamic stochastic general equilibrium models in a world which manifestly is not in equilibrium. But that doesn’t mean that these, and other mathematical models, have nothing to contribute. The redefinition of the foundations of economics that is currently being done by heterodox economists will inevitably result in many of the models beloved of academic economists becoming obsolete: as with much of the experimental serious” music of the 20th century, they will not survive the test of time. But there will be models that remain relevant, and there will be others that appear obsolete but that will in due course be redeveloped and find new life in the new economic paradigm. If we allow them to disappear, our economic understanding in the future will be the poorer.Contrary to the impression Noah gave, I was defending mainstream economics and its beloved mathematical models. But not because they have done a good job – they have not. And not because economics does not need a different paradigm. It does, desperately. Noah’s arrogant defence of mainstream economics shows this more clearly than anything the heterodox community could say.

We who live through this paradigm shift have a blinkered and biased view, rendering us unable to see the true value of either the old or the new. We either defend the old and reject the new, because the old is all we know and the new has yet to prove itself; or we reject the old and defend the new, because the old has failed and we need something to believe. These are, of course, extremes. The eventual synthesis will include elements of both old and new. In what proportions, history will decide.

And this brings me to my fundamental objection to Noah's post. Noah goes on to explain that heterodox economics can’t possibly work better than mainstream economics, because:

- it is not mathematical

- it is too vague to be any use for forecasting

- the models it uses are just revamped mainstream ones

- it over-fits data to its models, giving spurious results

- it hasn’t managed to produce any reliable results

How this can be seen as a ringing endorsement of mainstream economics is a mystery to me. But that is how Noah seems to want it to be interpreted.

Noah's arrogance seems to have elicited some rather defensive responses from the heterodox community, along the lines of “But we DO like mathematics!” or even, “Actually our mathematics is better than yours” (sorry, Steve). This unfortunately buys in to Noah's core proposition, which is that economics has no validity unless it is expressed in mathematical terms.

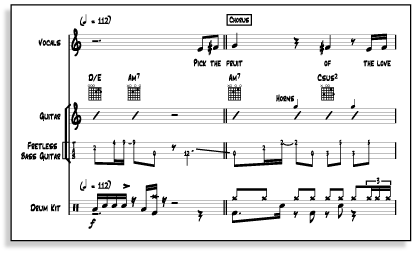

Noah says that economics without mathematics doesn’t add up. But economics consisting entirely of mathematics doesn’t add up either. Exclusive reliance on mathematics as language is highly problematic, and not just because it inevitably creates a protected elite. It is because of the impossibility of precision. To explain this, here is another musical analogy.

Anyone who has ever attempted to write down, in conventional musical notation, exactly what a jazz singer does knows how imprecise and inadequate musical notation is. Yet when it is removed from the source and viewed academically, it creates a kind of spurious precision. The original intention is demeaned and deformed to fit into the straitjacket of the notation, and the notation then “becomes” the music. Gifted performers, of course, interpret the music from the notation – but in bringing it to life, they re-create imprecision.

So too, relying on mathematical models to explain how our complex, ever-changing world works demeans and deforms it. The more precise a model is, the more unrealistic assumptions have to be made to make it work, and the less likely it is to be an adequate representation of reality. Reality is imprecise and transient.

The great economists of the past knew this - which is why we do not find pages of Greek symbols even in the writings of those who, like John Maynard Keynes, were fine mathematicians. And some members of the mainstream are beginning to realise that economics is much bigger than their beloved DSGE models. Olivier Blanchard, for example, recently called for a more diverse range of models, including "ad hoc" schematics that have little precision and much imagination. "There is room for both science and art", he said. Though he can't quite let go of the DSGE dream, not yet......

The heterodox economics community should - and in most cases does - reject Noah's core proposition outright. Economics is not, and cannot be, exclusively mathematical. This is the terrible mistake that the mainstream economists of our time have made.

The spurious precision of mathematics led "serious" music down the blind alley of serialism. And it has led mainstream economics down the blind alley of general equilibrium. I defend DSGE models, yes, but for their future possibilities, not for their current application.

There is no need for the heterodox economic community to be defensive about vagueness. Vagueness is creative, and imprecision and ad-hocery are the future. The art of economics is being reborn.

Related reading:

Where danger lurks - Olivier Blanchard

Colds, strokes and Brad Delong

The Slowly Changing Resistance of Economists To Change - Steve Keen (Forbes)

Image from Sibelius.