This article first appeared in the Indian journal Economic and Political Weekly on 19 March 2022.Russian Invasion of UkraineThe Russian invasion of Ukraine started on 24 February 2022. Since then, several thousand combatants from both sides and more than 500 Ukrainian civilians have died, bombs have ruined many cities, and more than two million Ukrainians, half of them children, left the country to become refugees. And the sweeping sanctions the West imposed on Russia in response not only devastated the Russian and Ukrainian economies but also brought the world to the brink of a deep global inflationary recession, worsening the economic hardship of the poor around the globe. Writing a cold-blooded analysis of the sanctions in the midst of witnessing this tragedy, one of the greatest in

Topics:

T. Sabri Öncü considers the following as important: Article, Financial Architecture, International & World, money & banking

This could be interesting, too:

Jeremy Smith writes UK workers’ pay over 6 years – just about keeping up with inflation (but one sector does much better…)

T. Sabri Öncü writes Argentina’s Economic Shock Therapy: Assessing the Impact of Milei’s Austerity Policies and the Road Ahead

T. Sabri Öncü writes The Poverty of Neo-liberal Economics: Lessons from Türkiye’s ‘Unorthodox’ Central Banking Experiment

Ann Pettifor writes Global Economic Governance: What’s “Growth” Got to Do with It?

This article first appeared in the Indian journal Economic and Political Weekly on 19 March 2022.

Russian Invasion of Ukraine

The Russian invasion of Ukraine started on 24 February 2022. Since then, several thousand combatants from both sides and more than 500 Ukrainian civilians have died, bombs have ruined many cities, and more than two million Ukrainians, half of them children, left the country to become refugees. And the sweeping sanctions the West imposed on Russia in response not only devastated the Russian and Ukrainian economies but also brought the world to the brink of a deep global inflationary recession, worsening the economic hardship of the poor around the globe. Writing a cold-blooded analysis of the sanctions in the midst of witnessing this tragedy, one of the greatest in recent history, feels awkward. Nevertheless, here it is.

Weaponisation of Everything

I encountered the term “weaponisation of everything” for the first time in a Reuters article by Nader Mousavizadeh on 25 September 2015. He wrote:[1]

… basic enablers of globalisation – finance, technology, energy, law, education, science, trade and travel – have all been turned into weapons in a new form of warfare. … What might be called the “weaponisation of everything” is the new reality of globalisation …

He then went into clarifying what he meant by giving concrete examples. But, today, the readers of the article can skip them. Because we now have an abundance of up-to-date ones. Since 21 February 2022, another “thing” gets weaponised against Russia almost every day. Rephrasing Jones and Powell (2022), the news around the weaponised things against Russia is moving so fast that nearly any article that one starts becomes horribly out of date by the time it gets completed.

21-22 February Sanctions

The Western sanctions imposed on Russia because of the Russia-Ukraine conflict started on 3 March 2014 after the Russian annexation of Crimea from Ukraine in February 2014. On 3 March 2014, the United States (US) suspended trade and investment and military-to-military cooperation talks with Russia, and a tsunami of Western sanctions broke out.[2] If I were to list all of the waves of this tsunami, I would run out of space. So, I jump to the sanctions of 21-22 February 2022.

In a speech on television on 21 February 2022, Putin announced that Russia recognised the independence of two pro-Russian breakaway regions, the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic and Luhansk People’s Republic in the east of Ukraine. A few hours later, he ordered Russian troops to move into Donetsk and Luhansk, presumably, to maintain peace.

Just hours after Putin’s televised speech, US President Biden signed an executive order issuing broad sanctions on Donetsk and Luhansk. Then came the other sanctions, issued or announced by the US, European Union (EU), United Kingdom (UK), Australia, Canada and Japan, targeting Russia, Donetsk and Luhansk, and followed up with additional sanctions targeting Russia’s financial system on 22 February 2022. However, these sanctions were relatively mild by historical standards.

An important announcement on 22 February 2022 came from German Chancellor Olaf Scholz. He announced that he had asked the German Economy Ministry to take steps

to make sure that this pipeline cannot be certified at this point in time, and without this certification, Nord Stream 2 cannot operate.[3]

Completed in September 2021 but not certified yet, Nord Stream 2 is an undersea gas pipeline from the Russian coast near St Petersburg to Lubmin in Germany that runs parallel to Nord Stream, an existing undersea gas pipeline working since 2011. Even without Nord Stream 2, the EU imported 155 billion cubic metres of natural gas from Russia in 2021. This amount accounted for around 45% of EU gas imports and about 40% of its total gas consumption. And the natural gas imported from Russia accounted for about 32% of Germany’s natural gas consumption in 2021. Given that Germany and the rest of the EU had resisted attempts to impose sanctions on Nord Stream 2 because of their heavy reliance on energy sources from Russia, this was a significant turn that paved the way for united actions of the West, at least, initially.

24 February Sanctions

When the Russian invasion of Ukraine started on 24 February 2022, the first mover was again the US, with sanctions against not only Russia but also against Belarus because Russian troops stationed in Belarus did most of the northern incursions. The US announced that the US Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC)

imposed expansive economic measures, in partnership with allies and partners, that target the core infrastructure of the Russian financial system — including all of Russia’s largest financial institutions and the ability of state-owned and private entities to raise capital — and further bars Russia from the global financial system.”[4]

The sanctions OFAC imposed on Belarus were more directed, focusing only on the financial and defence sectors.

Russia’s initial plan appeared as a war conducted with great speed and force, a blitzkrieg, probably built on the premise that Ukrainians would not resist. And the West appeared to have expected Ukraine would surrender rapidly. Probably partly because of this, and probably also because of resistance from the EU, the OFAC sanctions were more measured than advertised.

The 24 February OFAC sanctions consisted of: i) financial sanctions on some individuals and several Russian banks; ii) prohibition of the debt and equity issuance of major state-owned and private entities, including Sberbank, Gazprom, and Alrosa, and iii) export controls for exports of a wide range of items to Russia.

The sanctioned banks were Sberbank, VTB Bank, Bank Otkritie, Novikombank and Sovcombank. Sberbank and VTB are the first and second-largest banks in Russia, accounting for more than half of the entire Russian banking system by assets in the aggregate. Except for the Sberbank, the OFAC blocked the remaining banks, freezing any of their assets touching the US financial system and prohibiting US persons from dealing with them, effectively putting these banks out of the dollar clearing and settlement system immediately.

The OFAC sanctions on Sberbank were less severe, to take effect on 26 March 2022. At that time, the US financial institutions will no longer be able to i) open or maintain a correspondent account or payable-through account for or on behalf of, and ii) process transactions involving Sberbank, meaning the OFAC postponed the exclusion of Sberbank from the dollar clearing and settlement system for 30 days.

But this was not the only reason I claimed the OFAC sanctions were more measured than advertised. Even had the OFAC also excluded Sberbank from the dollar clearing and settlement system immediately, many other banks in Russia are still connected to the system, however small they may be. Unless the OFAC excludes all Russian banks from the dollar clearing and settlement system, nothing can stop dollars flowing into and out of Russia. Even a single bank of any size with a correspondent bank in New York is enough for Russian exporters and importers to make dollar payments to or receive dollar payments from their foreign trading partners.

Rather than criticising this, many criticised the US for being unable to broker a deal with the EU to cut off Russian banks from the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT), a Belgium-based global financial messaging service. First and foremost, SWIFT is just a secure communication tool among the banks, not a clearing and settlement system. Although being unable to access SWIFT would make bank to bank communications inconvenient, banks can always find other means to communicate, however cumbersome they may be. The only way to exclude a non-US bank from the dollar clearing and settlement system is by banning the bank from the correspondent banking network. Secondly, Germany and Italy had objected to banning Russian banks from SWIFT until then, so the US could not have brokered such a deal.

Then, on 25 February 2022, spectacularly failed Russia’s blitzkrieg plan in the face of heroic resistance by the Ukrainian military and its people and changed the course of history, as well as sanctions.

26-27 February Weekend

Before “[t]he brilliantly orchestrated spectacle of Ukrainian resistance (Tooze 2022)” of 24-25 February, the European Commission had been opposing the suspension of Russian banks from SWIFT. Further, SWIFT is a Belgium-based company and, therefore, subject to EU law. The US does not have any control over it. The consent of the European Commission is necessary. And the European Commission consented on 27 February for a partial ban of Russian banks from SWIFT. Although this partial ban is hardly a blow to the Russian economy for the reasons I gave already, its

real importance lies in the fact that 27 countries all agreed to implement it. It is a remarkable exhibition of common purpose and solidarity with Ukraine, which very much wanted the ban (Coppola 2022).

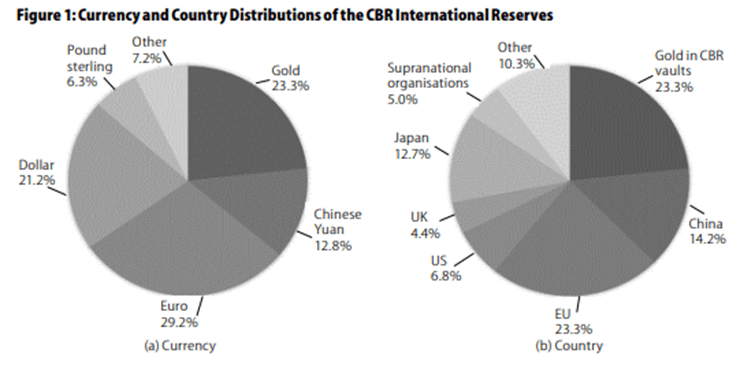

The real blow to the Russian economy was when the US, UK, Canada, France, Japan, Germany, Italy and the European Commission announced that they would prevent the Central Bank of Russia (CBR) from using its reserves held in their jurisdictions. According to Jones and Cotterill (2022), the currency and country distribution of roughly $630 billion CBR foreign exchange reserves as of the end of January 2022 were as in Figure 1.

Excluding the gold in vaults and reserves in China, we see from Figure 1 that this move made about 65% of the $630 billion CRB international reserves useless for supporting the rouble in the foreign exchange markets, servicing foreign currency debt and paying for imports in dollars and euros. Further, unless the CBR can convert its yuans and gold to dollars and euros, Russia cannot use them for these purposes either.

We may call the above weaponisation of the central bank reserves. Combine it with the weaponisation of correspondent banking networks as I described above, and you are looking at the deadliest financial weapon imaginable. Further, this weapon would kill Russia’s foreign trade in dollars and euros also. But, of course, such deadly financial weapons can backfire and harm their creators also, as I will discuss later.

Sanctions After 26-27 February

The first response of the CBR in the morning of 28 February was to hike its policy rate from 9.5% to 20%. Then, Putin signed into law a decree ordering exporting companies to sell 80% of all types of foreign currency revenues they have received since the beginning of 2022 and banned foreign exchange loans and transfers by Russian residents to the outside of Russia effective 1 March. Further, the CBR temporarily banned brokers from executing foreign sell orders and closed the Moscow stock exchange, which crashed about 24% from the close of 23 February to the close of 25 February. The crash on 24 February was 33%. The Moscow stock exchange is yet to open as of 14 March. Moreover, the rouble crashed about 20% against the dollar on 28 February. It has lost about 60% of its value against the dollar from 20 February to 14 March as of writing.

Statistica reports that the number of sanctions against Russian individuals and entities imposed by the US, the EU and select countries like Switzerland, the UK and Japan between 22 February and 8 March was 2827, of which 366 on entities and remaining on individuals.[5]

On 2 March, the EU announced the disconnection of seven Russian banks from SWIFT as of 12 March 2022. These banks are VTB Bank, Bank Otkritie, Novikombank, Sovcombank, Promsvyazbank, Bank Rossiya and Vnesheconombank. Although the OFAC effectively put the first four of these banks out of the dollar clearing and settlement system on 24 February 2022, the other three remain connected to it. Further, all seven banks remain in correspondent banking networks for currencies other than the US dollar. Therefore, whether this sanction would impact the Russian economy or not is open to debate for reasons I gave already. Furthermore, the EU exempted Sberbank and Gazprombank — the two Russian banks that handle most of the payments related to gas and oil exports — from the SWIFT ban, indicating that the Western unity is probably weaker than advertised when it comes to the critical issue of energy sources.

Lastly, although President Biden banned imports of Russian oil and gas into the US, and the UK Business Secretary Kwarteng followed suit by confirming that the UK will phase out imports of Russian oil on 8 March 2022, the response from the EU countries was mixed. Moreover, the UK announced that

[t]he phasing out of imports will not be immediate, but instead allows the UK more than enough time to adjust supply chains, supporting industry and consumers.”[6]

So Much for the Western Unity

One thing is clear. As long as Germany and other EU countries continue importing gas and oil from Russia — as the data the International Institute of Finance puts out show — Russia will not run out of dollars and euros to pay for its imports. [7] And this is despite all the financial, trade and travel weapons fired at it by now. Many have questioned whether the sanctions imposed so far have been strong enough to convince Russia to come to the peace table or not, and the debate continues.

Who is Losing the War?

The number of casualties in Ukraine and refugees — mainly women, children and elderly — fleeing Ukraine is growing by the day. Not only the economies of Ukraine and Russia are collapsing, but the skyrocketing prices of energy, agricultural products from wheat to sunflower oil and even fertilisers are also fanning the worldwide inflation fire that started way before the invasion. The already high food inflation

is now tipping into a full-blown crisis, potentially outstripping even the pandemic’s blow and pushing millions more into hunger.[8]

These are just a few examples of the devastating effects of the ongoing invasion. I can list more, but even this much should be enough. Unless the world ends the war in Ukraine today, we all are losing. Our goal must be to bring peace to Ukraine now. And the Western sanctions imposed on Russia do not appear effective in achieving this goal. There must be another way.

T. Sabri Öncü ([email protected]) is with Bahçeşehir University Financial Research Centre in İstanbul, Turkey.

REFERENCES

Coppola, Frances, 2022, “Sanctions against Russia contain a crucial exemption that lessens the pain,” MarketWatch, 1 March. https://www.marketwatch.com/story/sanctions-against-russia-contain-a-crucial-exemption-that-lessens-the-pain-11646149512

Jones, Clair, and Joseph Cotterill, 2022, “Russia’s FX reserves slip from its grasp: Officials in Moscow will be hard pressed to halt a collapse in the rouble. Here’s why,” Financial Times, 28 February. https://www.ft.com/content/526ea75b-5b45-48d8-936d-dcc3cec102d8

Jones, Clair, and Jamie Powell, 2022, “Commodities go crazy: We could be set for our most volatile week ever,” Financial Times, 7 March. https://www.ft.com/content/7db838e3-6dc0-45e1-83ba-c8ce1c5544a5

Tooze, Adam, 2022, “The world is at financial war: The freezing of Russia’s central bank reserves has brought conflict to the heart of the international monetary system,” The New Statesman, 2 March. https://www.newstatesman.com/ideas/2022/03/ukraine-the-world-is-at-financial-war

[1]https://www.reuters.com/article/mousavizadeh-globalization-idUSL1N11V2KZ20150925

[2]https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-sanctions-timeline/29477179.html

[3]https://www.cnbc.com/2022/02/22/germany-halts-certification-of-nord-stream-2-amid-russia-ukraine-crisis.html

[4]https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0608

[5]https://www.statista.com/chart/27015/number-of-currently-active-sanctions-by-target-country/

[6]https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-to-phase-out-russian-oil-imports

[7]https://twitter.com/RobinBrooksIIF/status/1502296482728316933

[8]https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-03-08/war-in-ukraine-compounds-global-food-inflation-hunger-crisis